Three years ago, NASA awarded a cost-plus contract to the engineering firm Bechtel for the design and construction of a large, mobile launch tower. The 118-meter tower will support the fueling and liftoff of a larger and more capable version of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket that may make its debut during the second half of this decade.

When Bechtel won the contract for this mobile launcher, named ML-2, it was supposed to cost $383 million. But according to a scathing new report by NASA’s inspector general, the project is already running years behind schedule, the launcher weighs too much, and the whole thing is hundreds of millions of dollars over budget. The new cost estimate for the project is $960 million.

“We found Bechtel’s poor performance is the main reason for the significant projected cost increases,” the report, signed by Inspector General Paul Martin, states. The report finds that Bechtel underestimated the project’s scope and complexity. In turn, Bechtel officials sought to blame some of the project’s cost increases on the COVID-19 pandemic.

As of this spring, NASA had already obligated $435.6 million to the project. However, despite these ample funding awards, as of May, design work for the massive launch tower was still incomplete, Martin reports. In fact, Bechtel now does not expect construction to begin until the end of calendar year 2022 at the earliest.

Many mistakes

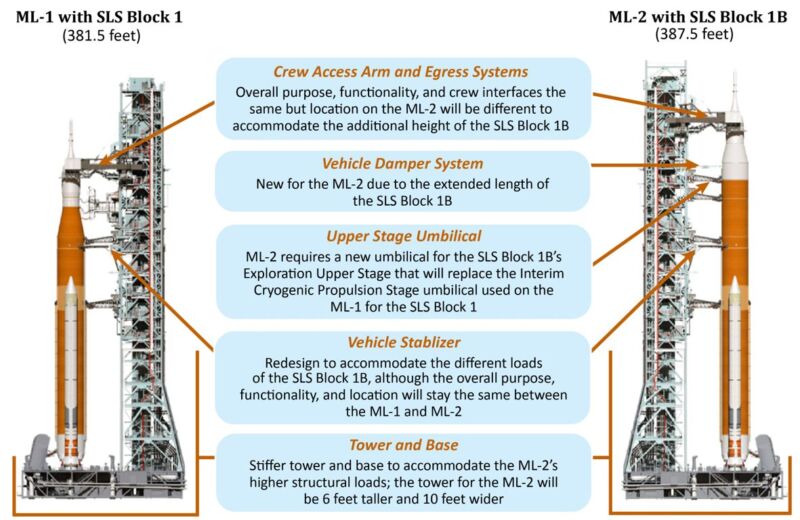

The report cites a litany of mistakes by the contractor, Bechtel, but does not spare NASA from criticism. For example, Martin said that NASA awarded the contract to Bechtel before the specifications for the Space Launch System rocket’s upper stage were finalized. (The major upgrade to the rocket will come via a more powerful second stage, known as the Exploration Upper Stage, or EUS). This lack of final requirements to accommodate the EUS hindered design of the mobile launch tower, which must power and fuel the rocket on the ground.

NASA’s explanation for doing this is that it had no choice but to move forward with the tower’s design and construction to meet a timeline for its lunar missions. The first three flights of the Artemis Program, culminating in a human lunar lander no earlier than 2025, are to fly on the initial variant of the Space Launch System rocket (which has its own, separate mobile launch tower). However, beginning with the Artemis IV mission, NASA wants to launch lunar missions on the more powerful, upgraded version of the SLS rocket, which will require the new mobile launch tower.

Nominally, this mission is planned for 2026, but realistically it will not fly before 2027 or 2028, due to delays in the earlier Artemis flights. Nevertheless, NASA pressed for the construction of this second mobile launch tower to be ready for 2026 and asked for design work to be done on the tower before the rocket’s final requirements were known. This is likely to result in additional costs, pushing the price of the second mobile launch tower above $1 billion.

“We expect even greater cost increases because NASA anticipates the potential for additional changes due to finalization of EUS requirements and technical challenges once ML-2 construction begins,” the new report states. “In light of these issues, NASA is reevaluating the ML-2 project’s budget and schedule estimates to provide a more accurate representation of the projected increases.”

Plague of cost-plus

Still, Martin attributes the majority of the issues with the project’s cost and delays to Bechtel. It has gotten so bad that NASA has taken the extraordinary step of removing work from Bechtel’s plate without reducing its payments to the contractor. In early 2022, to allow Bechtel to better focus on the core project, NASA and Bechtel agreed to take the development of the umbilicals out of the contract. NASA will use a different contractor for these cables and hoses and provide them to Bechtel for integration into the tower.

In light of the spiraling costs, NASA sought to move the remaining work on the mobile launcher contract from a cost-plus contracting mechanism, in which the government is responsible for overruns, to a fixed-price contract, in which the private contractor assumes the financial risks. The report states that such an agreement has not yet been reached, however.

The mobile launch tower’s development woes, and the impending release of Martin’s report, have been a growing concern among senior NASA officials who are worried about Congressional blowback.

In early May, during testimony to the US Congress, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson was contemplating the launch tower’s immense costs when he took aim at cost-plus contracts. Citing the virtues of fixed-price contracts, Nelson said, “You get it done cheaper, and that allows us to move away from what has been a plague on us in the past, which is a cost-plus contract, and move to an existing contractual price.”

Listing image by NASA/David Zeiters

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1858393