In Tim Burton’s 1993 animated feature The Nightmare Before Christmas, there’s a scene where a little boy receives a shrunken head as a Christmas gift from Jack Skellington. It does not go over well, with either the boy or his parents. But there was a time in the early 20th century when these macabre objects were in such great demand by Western collectors that it triggered a lucrative market for counterfeits. Many museums around the world count shrunken heads (known as tsantsas by the Shuar people) among their collections, but how can curators determine if those items are authentic? Certain sophisticated imaging methods can help, according to an August paper published in the journal PLoS One.

The practice of headhunting and making shrunken heads has mostly been documented in northwestern parts of the Amazon rainforest, as well as among certain tribes in Ecuador and Peru, like the Shuar. Accounts conflict on the specific details of the manufacturing process. But the tsantsas were typically created by removing the skin and flesh from the skull’s cranium via an incision on the back of the ear, and then discarding the skull. The nostrils were packed with red seeds and the lips sewn shut. Next, the skin was boiled in water saturated with tannin-rich herbs for 15 minutes to two hours, so that the fat and grease would float to the top. This also caused the skin to contract and thicken. Then the head was dried with hot rocks and molded back into something resembling human features and the eyes were sewn shut. As a final touch the skin was rubbed with charcoal ash—apparently to keep the avenging soul from escaping—and sometimes beads, feathers, or other adornments were added for decoration.

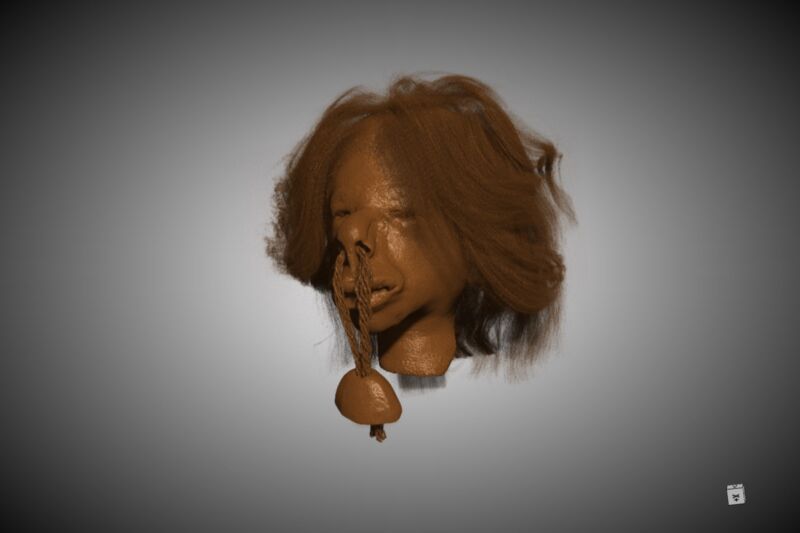

Traditionally, the completed tsantas were displayed on poles inside houses—not worn, per the authors of the August paper, despite what one might read in the existing anthropological literature. Shrunken heads were a popular collectible among Victorian-era priests, Europeans, and American explorers eager to bring exotic things back for their private collections. Eventually a commercial market developed as the practice became more broadly known after 1860. But these commercial tsantsas were often made from animal skins (usually pigs, monkeys, or sloths), although some were made from human heads collected from corpses in morgues. The manufacturers nonetheless claimed their wares were genuine.

Lauren September Poeta of Western University in London, Ontario, and her coauthors estimate that as much as 80 percent of the tsantsas currently kept in collections worldwide are of commercial origin, and there are very few reliable methods capable of determining their true origin. Curators have usually relied on visual inspections or CT scanning for authentication. But Poeta et al. note that four key features are poorly resolved using standard CT scanning: the stitching, eye anatomy, ear anatomy, and scalp anatomy. So they decided to see if they could improve the resolution of those features by combining CT scanning with high-resolution micro-CT scanning—an approach known as correlative tomography.

-

The Chatham tsantsaL.S. Poeta et al., 2022

-

Digital micro-CT visualization of posterior incision and stitching.L.S. Poeta et al., 2022

-

Micro-CT image of a thread reaching across the posterior incision.L.S. Poeta et al., 2022

The team used a tsantsa from the collection of the Chatham-Kent Museum in Chatham, Ontario, acquired by the museum in the 1940s from a local family who bought it while exploring the Amazonian basin. The only note of origin was that it came from “Peruvian Indians,” and there was no definitive proof that the Chatham tsantsa was the genuine article. The researchers did a clinical CT scan of the entire object and two micro-CT scans—one of the whole head, the other a high-resolution scan of part of the scalp—using a machine at the Museum of Ontario Archaeology.

Poeta and her colleagues confirmed that the Chatham tsantsa is made of genuine human remains, although they could not determine whether it was made ceremonially or commercially. The rough cut at the back of the skull and the use of double-hiding are consistent with the former, but modern thread was used to stitch the incision, eyes, and lips, which suggests commercial production. “In fact, it may be that the division between ceremonial and commercial manufacture is more difficult to define than generally believed, as the practice of creating tsantsas likely exists on a spectrum rather than an either/or dichotomy,” the authors wrote.

More might be learned by subjecting tsantsas of known provenance to correlative tomography imaging. The authors concluded that while conventional CT scanning remains useful for reconstructing a basic visualization of these fascinating artifacts—enabling researchers to closely examine them without risking damage from repeated handling—micro-CT scanning can determine whether a given tsantsas is made of human materials, and provide higher resolution details for specific features.

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0270305 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1870586