The Food and Drug Administration on Friday granted a fast-tracked approval for a new Alzheimer’s disease treatment, which may slightly slow the progression of cognitive decline in the disease’s early stages, but also raises risks of brain bleeds and swelling.

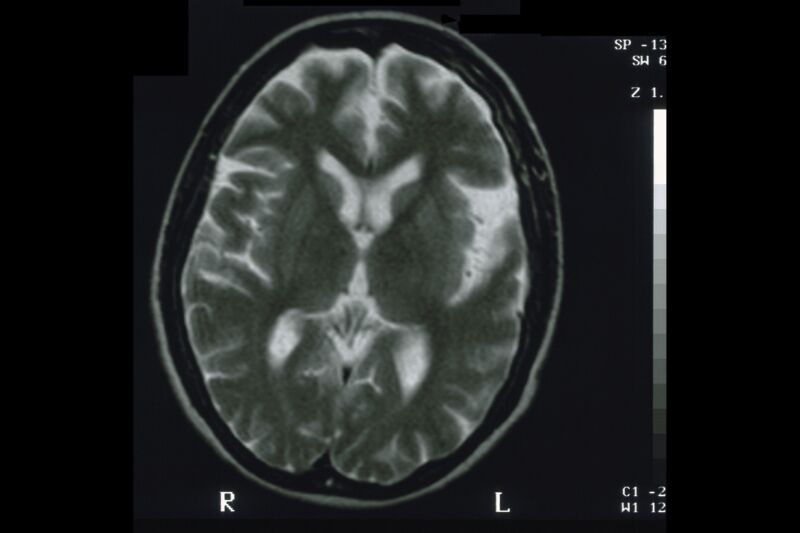

The treatment—lecanemab, brand name Leqemb, made by pharmaceutical companies Eisai and Biogen—is an intravenous monoclonal antibody that targets amyloid-beta proteins, which accumulate in plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. Researchers have not yet conclusively determined if amyloid plaques are a root cause of the disease, nor whether clearing them can significantly slow or halt cognitive decline.

The FDA’s approval of lecanemab is via an accelerated pathway, which uses “a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict a clinical benefit to patients.” In this case, the surrogate endpoint was lecanemab’s ability to reduce amyloid beta plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

Uncertain efficacy

But, the significance of that and the drug’s efficacy are still uncertain. In a Phase III clinical trial, published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine, treatment with lecanemab over 18 months only slightly slowed cognitive decline in patients with early Alzheimer’s. The trial included 1,795 participants—898 were assigned to receive lecanemab and 897 were assigned a placebo. Their cognitive abilities were assessed using an 18-point scale from an established clinical test for dementia. At the start of the trial, both groups (treatment and placebo) has a baseline score of about 3.2 on the test. After the 18-month trial, the lecanemab treatment group’s score fell by 1.21 points, while the placebo group’s fell by 1.66 points—a 0.45-point difference that amounts to a 27 percent slower decline in the treatment group.

It’s unclear if that change is meaningful. Dr. Madhav Thambisetty, a neurologist and a senior investigator at the National Institute on Aging who spoke with The New York Times, said that the drug’s ability to clear amyloid plaques was “exciting,” from the perspective of a scientist. But, “from the perspective of a physician caring for Alzheimer’s patients, the difference between lecanemab and placebo is well below what is considered to be a clinically meaningful treatment effect.“

The researchers behind the clinical trial noted in their conclusion that “Longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Safety concerns

Meanwhile, the treatment has raised safety concerns, particularly amid reports that three patients given the drug have died from brain swelling and bleeding. That includes a 65-year-old woman with early stage cognitive decline who died of a massive brain hemorrhage. Rudolph Castellani, a Northwestern Medicine neuropathologist who studies Alzheimer’s and conducted an autopsy on the woman at the request of her husband, told Science last November that he believed that the drug weakened the woman’s blood vessels, which then burst from a common treatment for blood clots after she had a stroke.

“It was a one-two punch,” Castellani told Science, which first reported the death. “There’s zero doubt in my mind that this is a treatment-caused illness and death. If the patient hadn’t been on lecanemab she would be alive today.”

A report of the woman’s death was also published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Lecanemab’s prescribing information includes warnings and cautions about brain bleeding and swelling, and the use of blood thinners.

The FDA’s approval comes just a week after lawmakers released the results of an 18-month Congressional investigation into the agency’s much-criticized approval of a similar Alzheimer’s drug, Aduhelm. Data on that amyloid-targeting antibody therapy was even less conclusive than lecanamab’s, and the FDA granted approval over objections from its external advisory panel and internal experts.

Irregularities

The Congressional investigation found the FDA’s approval process “rife with irregularities” and “inappropriate” communications between FDA and Aduhelm’s maker, Biogen. The report also blasted Biogen for setting “an unjustifiably high price” of $56,000 a year for Aduhelm.

“This report documents the atypical FDA review process and corporate greed that preceded FDA’s controversial decision to grant accelerated approval to Aduhelm,” Energy and Commerce Committee incoming Ranking Member Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ), said at the time.

Following the approval of lecanemab, Pallone released a statement saying: “I’m hopeful lecanemab will live up to its promise of slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease for patients and their loved ones. I’m also hopeful Eisai and Biogen have learned from past mistakes and will price lecanemab fairly to ensure patients have equitable access to this drug.

In a press release Friday afternoon, Eisai announced that it is pricing lecanemab at $26,500 for a year’s supply. That is above the range that the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review estimated would make the drug cost-effective, which the analysis group pegged at between $8,500 and $20,600 for a year’s worth of treatment.

It’s unclear if Medicare will cover lecanemab, which will dramatically influence its marketability. Medicare strictly limited coverage of Aduhelm, due to the high price, lack of evidence of benefit, and risks. Only Medicare beneficiaries in clinical trials have coverage for the price of Aduhelm, which has since been cut to $28,200 for a year’s supply.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1908494