French volcanologists Maurice and Katia Krafft carved out an illustrious career by daring to go where most of their colleagues feared to tread: right to the edge of an erupting volcano. The photographs and video footage they recorded during the 1970s and 1980s contributed to significant breakthroughs in their chosen field. Alas, the couple’s luck ran out on June 3, 1991, when they were killed by a massive pyroclastic flow from the eruption of Mount Unzen in Japan. The striking image above of Katia Krafft in a protective heat suit, dwarfed by a wall of fire, is just one of many powerful moments featured in Fire of Love, a 2022 National Geographic documentary about this extraordinary couple that is now streaming on Disney+.

Director Sara Dosa was scouring archival images of volcano imagery for one of the segments in her previous documentary (The Seer and the Unseen) set in Iceland when she came across the story of the Kraffts. “I became completely hooked on the nature of their relationship,” she recalled. “It wasn’t just Maurice and Katia in a relationship; it was almost a love triangle between the two of them and the volcanoes.” Apart from a handful of new footage shot by cinematographer Pablo Alvarez-Mesa, the entire film is composed of archival footage.

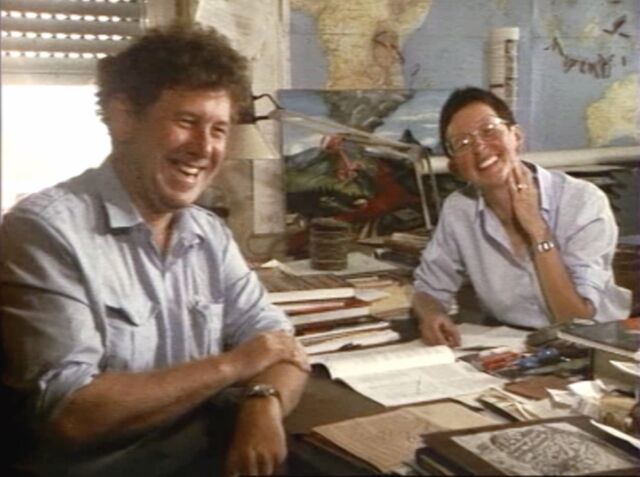

Maurice and Katia (nee Conrad) Krafft met at the University of Strasbourg and married in 1970. Katia earned degrees in physics and chemistry, while Maurice studied geology. He had been fascinated by volcanoes since he was 7 years old during a family trip to Naples and Stromboli. Katia shared that fascination, and one of their first excursions as a couple was to Stromboli, where they photographed its eruption.

That launched their career as volcanologists. They were often the first to show up at an active volcano, often going right to the edge to capture vivid still photographs and video of eruptions, creating footage that was the envy of their peers. Katia would also take gas readings and mineral samples and carefully record the data. She wrote numerous books to help fund their many trips and even made a volcano documentary for PBS. And they often relied on giving talks at nursing homes to drum up funding, according to Leanne Wiberg, who knew the Kraffts while working at the Smithsonian some 30 years ago.

The Kraffts traveled relatively lightly in terms of personal items, preferring to reserve the limited suitcase space for their gear. “They would go to Goodwill stores in the US when they landed, because if a volcano erupted, they couldn’t go back to France to get their favorite camera and hot suits,” Wiberg told Ars. “The hot suits alone took up a whole suitcase. Their supplies would be shipped from France. So they didn’t have any luxuries or extra clothing.”

The couple decided to document the eruption of Mount Unzen in the late spring of 1991. There had been several small debris flows beginning on May 15 of that year, with the first small pyroclastic flow forming on May 24. Several more small pyroclastic flows occurred over the next several days, and much of the surrounding area was evacuated. But the Kraffts, American geologist Harry Glicken, several media teams, and assorted locals remained, perhaps lulled into a false sense of security about their ability to steer clear of the pyroclastic flows.

“The goal was for Maurice to get a side profile view of the pyroclastic flow,” said Wiberg. “The laminar flow is slower than the billowing overlap on the top. That’s why they have these cauliflower-pluming shapes. [The Kraffts] set up on a ridge that they thought would be far enough away to be protected by another ridge. But things didn’t go as expected.”

Accounts differ as to what triggered the massive pyroclastic flow on June 3—10 times bigger than the earlier flows—but it’s possible the culprit was the half a million cubic meters of hardened lava that broke off when the lava dome collapsed. According to geologist Jess Phoenix, author of Ms. Adventure: My Wild Explorations in Science, Lava, and Life (the paperback comes out next month), pyroclastic flows can move as fast as 435 mph (700 kilometers per hour). “I can’t overemphasize how destructive pyroclastic flows are,” Phoenix told Ars, likening the flows to a highly effective bulldozer. “You’ve got heavy rocks of varying sizes on the bottom of the pyroclastic flow, and a super-heated cloud of glowing ash and gas higher up. They are strong enough to wipe town buildings out of existence. And if there’s a reinforced structure with concrete and rebar, the rebar will be bent over sideways.”

Those still in the danger zone had no chance against the fast-moving flow. The Kraffts’ bodies were found lying side by side near their rental car, burned beyond recognition, while Glicken’s body was found a bit farther away. The 43 casualties also included 16 members of the media, 12 firefighters, four taxi drivers, two police officers, two city council workers, and four local farmers. The Kraffts’ footage of the event was destroyed, but in 2005, another (melted) video camera by a media reporter who had died was recovered, and the tape was miraculously still playable.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1910139