Earlier this week, the US’ Energy Information Agency (EIA) gave a preview of the changes the nation’s electrical grid is likely to see over the coming year. The data is based on information submitted to the Department of Energy by utilities and power plant owners, who are asked to estimate when generating facilities that are planned or under construction will come online. Using that information, the EIA estimates the total new capacity expected to be activated over the coming year.

Obviously, not everything will go as planned, and the capacity estimates represent the production that would result if a plant ran non-stop at full power—something no form of power is able to do. Still, the data tends to indicate what utilities are spending their money on and helps highlight trends in energy economics. And this year, those trends are looking very sunny.

Big changes

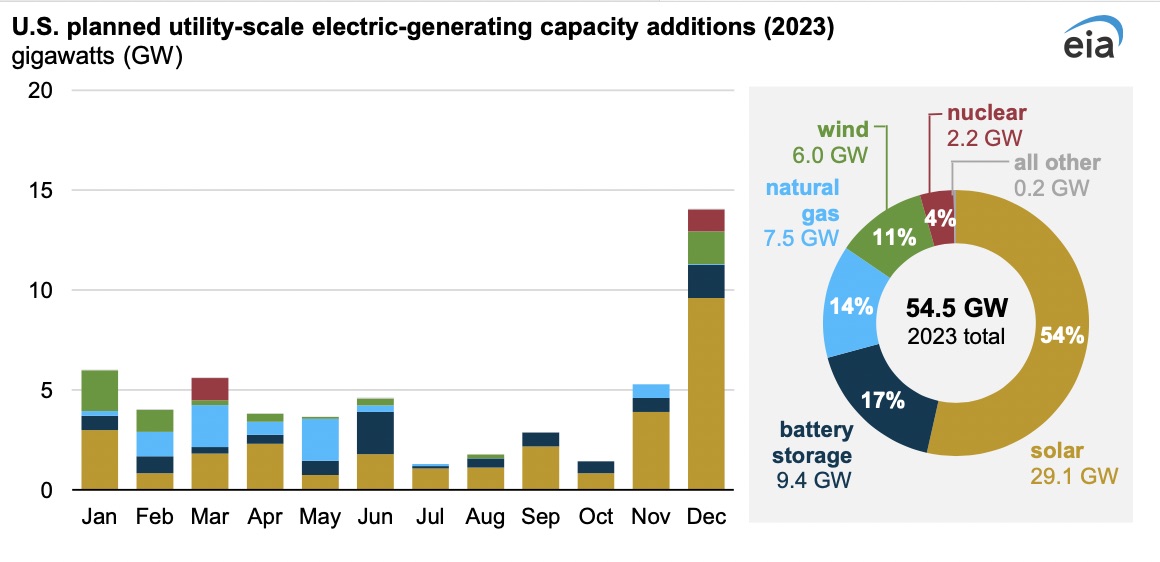

Last year, the equivalent report highlighted that solar power would provide nearly half of the 46 gigawatts of new capacity added to the US grid. This year, the grid will add more power (just under 55 GW), and solar will be over half of it, at 54 percent. In most areas of the country, solar is now the cheapest way to generate power, and the grid additions reflect that. The EIA also indicates that at least some of these are projects that were delayed due to pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions.

As has been typical, Texas and California will account for the lion’s share of the 29 GW of new capacity, with Texas alone adding 7.7 GW, and California another 4.2 GW.

Another trend that’s apparent is the reversal of the vast expansion in natural gas use following the development of fracking. Last year, natural gas generation accounted for 9.6 GW of the new capacity; this year, that figure is shrinking to 7.5 GW. And, strikingly, the EIA indicates that 6.2 GW of natural gas generating capacity is going to be shut down this year, meaning that there’s a net growth of only 1.2 GW. Should current trends continue, we may actually see a net decline in natural gas generating capacity next year.

The last big trend is the rapid growth of batteries. While these don’t generate electricity, they are increasingly providing the equivalent function of a power plant, in the sense that they send power to the grid when it’s needed. However you want to view them, they’re booming, going from 11 percent of the new capacity last year (5.1 GW) to 17 percent this year. At 9.4 GW of new batteries, the additions have nearly doubled in just a year, pushing the new battery capacity ahead of natural gas and into second place.

And the rest

While it doesn’t represent a trend, there’s also big news for nuclear power: The last two reactors that had been under construction at the Vogtle site in Georgia will be coming online. Their operators expect that one of the 1.1 GW plants will start operating in March, and the second in December. Given the plant’s history of delays, it will be no surprise if the latter slips into next year.

Even if everything goes smoothly, we’re unlikely to see any other nuclear additions until the end of the decade. But the planned reactors in the works are small modular designs that haven’t been built previously, so the chances of them being completed on time seem remote.

The other major source of additions, wind power, appears to have entered a period of stagnation. It saw a burst of new construction at the start of the decade in advance of expiring tax credits. But, even though those credits were restored by the Inflation Reduction Act, construction of new facilities hasn’t returned to its previous levels. Only six gigawatts of new wind are expected this year, down slightly from last year. Things may pick up in the second half of the decade as planners take the Inflation Reduction Act into account and offshore wind facilities start construction.

The final piece of the story is the continued decline in coal plants. No new ones will be completed this year, and none are in planning. By contrast, nearly nine gigawatts of existing coal facilities will be shut down. Even without the environmental problems it creates fully incorporated into the cost of coal power, the economics are simply brutal for existing operators, and they’re rapidly exiting the market.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1916933