For gamers of a certain age, the ’90s break up of Doom co-creators John Carmack and John Romero is a cultural moment on par with the breakup of The Beatles. Now, as the 30th anniversary of Doom‘s original release approaches next month, the pair has announced plans to come together for a moderated livestreamed discussion of their most famous creation.

The Twitch-streamed event, announced on social media late last week by Romero, will take place on Doom‘s anniversary of December 10. Carmack and Romero will discuss the game and its legacy with moderator and Rocket Jump author David L. Craddock, whom Ars readers might remember from the Long Live Mortal Kombat excerpt that ran on the site last year.

Carmack and Romero reuniting might feel like a historic burying of the hatchet to those who have followed the pair’s story over the decades. But “the two Johns” say that reports of their falling out have been exaggerated over the years, to say the least.

Past Masters

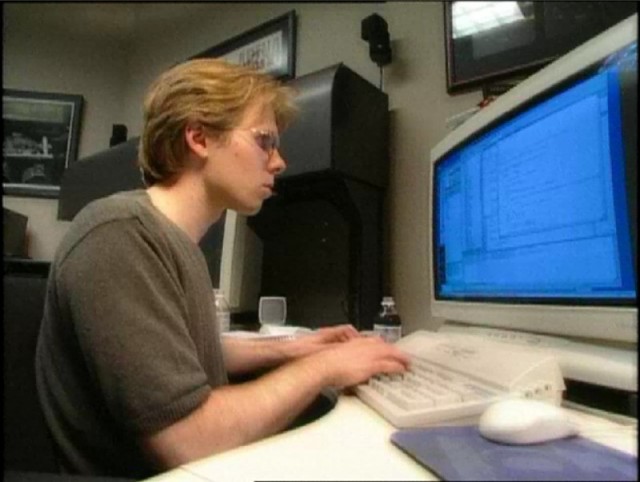

Plenty has been made of the tensions that developed between Carmack and Romero, who were still in their early 20s when the runaway success of the first two Doom titles made them PC game development royalty. As laid out in David Kushner’s history Masters of Doom, though, cracks in the two Johns’ relationship started to come to a head during the development of Quake. During that period, Carmack created a time-logging program that he said definitively showed Romero was slacking off on his work responsibilities.

(Update: Romero takes issue with this story in his recent memoir, writing that the time-tracking story actually took place at Cygnus Studios. “Carmack never programmed anything on my computer, a fact I’ve confirmed with him, nor did he give me a list of my hours,” Romero wrote. “Rather, he accused me of not being fully focused on Quake.”)

Romero was “talking too much to the press, talking too much to the fans, deathmatching too much in the office, and now the rest of the company was suffering,” Kushner writes by way of summarizing Carmack’s feelings in late 1995. “We need to put Romero on the record that he is about to be fired.”

While Romero’s career at id Software survived that period with nothing but a small hit to his annual bonus, the accusations had an effect. According to Masters of Doom, Romero started to feel his ambitious, fantasy-inspired design for Quake wasn’t being given the respect it deserved from the rest of the team, which was more interested in making Quake into a Doom-style game that showed off Carmack’s revolutionary new 3D engine. When Carmack declared the coveted level slots for Quake‘s shareware release would go to newcomer Tim Willits instead of Romero, it was close to the final straw.

Romero left id shortly after Quake‘s June 1996 release, announcing the departure in his one and only plan file update. “I have decided to leave id Software and start a new game company with different goals,” he wrote on August 7. “I won’t be taking anyone from id with me.”

“Romero is now gone from id,” Carmack wrote in an August 8, 1996, plan file update. “There will be no more grandiose statements about our future projects. I can tell you what I am thinking, and what I am trying to accomplish, but all I promise is my best effort.”

The life paths for the two Johns diverged wildly from that point. Carmack continued working on game engine tech at id until 2013, when he moved on from the Bethesda-owned company to a full-time focus on his CTO role at VR headset-maker Oculus (now Meta). Just nine years later, Carmack left Meta with a frustration-filled departure message and now puts his professional time into AGI startup Keen Technologies.

Romero, on the other hand, saw his post-id reputation suffer following the infamously hyped and ill-received release of FPS Daikatana in 2000. But he stuck it out in the game development world, working on design and programming for dozens of games throughout the 2000s. In recent years, the Romero Games label has played host to Sigil, a Doom WAD file marketed as “the unofficial fifth episode” of the game (Sigil II will launch on December 10). Last year, Romero also started publicly recruiting for “an all-new FPS with an original, new IP” running on Unreal Engine 5.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1981802