Research has shown that if you point at an object, a dog will interpret the gesture as a directional cue, unlike a human toddler, who will more likely focus on the object itself. It’s called spatial bias, and a recent paper published in the journal Ethology offers potential explanations for why dogs interpret the gesture the way that they do. According to researchers at Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary, the phenomenon arises from a combination of how dogs see (visual acuity) and how they think, with “smarter” dog breeds prioritizing an object’s appearance as much as its location. This suggests the smarter dogs’ information processing is more similar to humans.

The authors wanted to investigate whether spatial bias in dogs is sensory or cognitive, or a combination of the two. “Very early on, children interpret the gesture as pointing to the object, while dogs take the pointing as a directional cue,” said co-author Ivaylo Iotchev. “In other words, regardless of the intention of the person giving the cue, the meaning for children and dogs is different. This phenomenon has previously been observed in dogs using a variety of behavioral tests, ranging from simple associative learning to imitation, but it had never been studied per se.”

Their experimental sample consisted of dogs used in a previous 2018 study plus dogs participating specifically in the new study, for a total of 82 dogs. The dominant breeds were border collies (19), vizslas (17), and whippets (6). Each animal was brought into a small empty room with their owner and one of the experimenters present. The experimenter stood 3 meters away from the dog and owner. There was a training period using different plastic plates to teach the dogs to associate either the presence or absence of an object, or its spatial location, with the presence or absence of food. Then they tested the dogs on a series of tasks.

For instance, one task required dogs to participate in a maximum of 50 trials to teach them to learn a location of a treat that was always either on the left or right plate. For another task, the experimenter placed a white round plate and a black square plate in the middle of the room. The dogs were exposed to each semi-randomly but only received food in one type of plate. Learning was determined by how quickly each dog ran to the correct plate.

Once the dogs learned those first two tasks, they were given another more complicated task in which either the direction or the object was reversed: if the treat had previously been placed on the right, now it would be found on the left, and if it had previously been placed on a white round plate, it would now be found on the black square one. The researchers found that dogs learned faster when they had to choose the direction, i.e., whether the treat was located on the left or the right. It was harder for the dogs to learn whether a treat would be found on a black square plate or a white round plate.

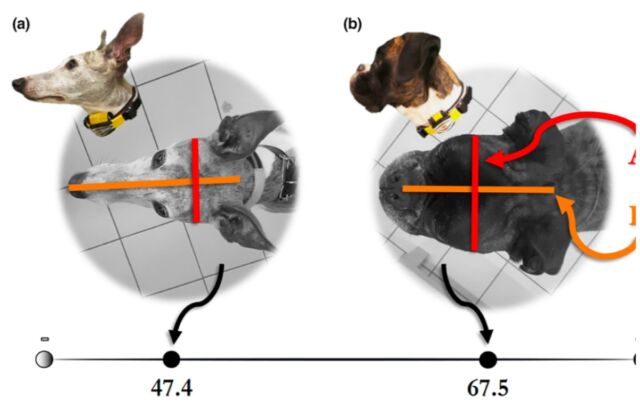

Next the team needed to determine differences between the visual and cognitive abilities of the dogs in order to learn whether the spatial bias was sensory or cognitively based, or both. Selective breeding of dogs has produced breeds with different visual capacities, so another aspect of the study involved measuring the length of a dog’s head, which prior research has shown is correlated with visual acuity. The metric used to measure canine heads is known as the “cephalic index” (CI), defined as the ratio of the head’s maximum width multiplied by 100, then divided by the head’s maximum length.

The shorter a dog’s head, the more similar their visual acuity is to human vision. That’s because there is a higher concentration of retinal ganglion cells in the center of their field of vision, making vision sharper and giving such dogs binocular depth vision. The testing showed dogs with better visual acuity, and who also scored higher on the series of cognitive tests, also exhibited less spatial bias. This suggests that canine spatial bias is not simply a sensory matter but is also influenced by how they think. “Smarter” dogs have less spatial bias.

As always, there are a few caveats. Most notably, the authors acknowledge that their sample consisted exclusively of dogs from Hungary kept as pets, and thus their results might not generalize to stray dogs, for example, or dogs from other geographical regions and cultures. Still, “we tested their memory, attention skills, and perseverance,” said co-author Eniko Kubinyi. “We found that dogs with better cognitive performance in the more difficult spatial bias task linked information to objects as easily as to places. We also see that as children develop, spatial bias decreases with increasing intelligence.”

DOI: Ethology, 2023. 10.1111/eth.13423 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1984913