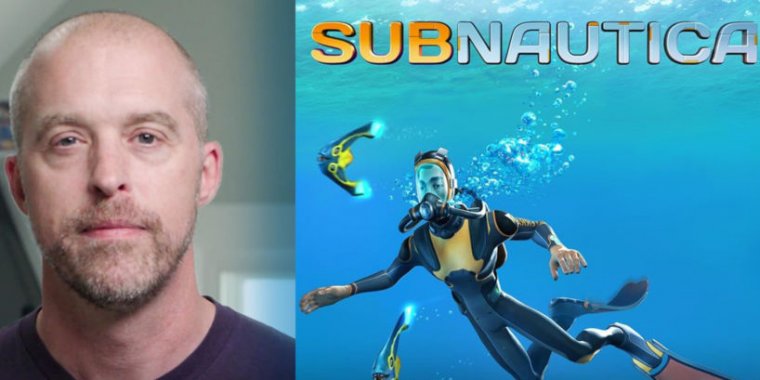

In the aftermath of the Sandy Hook school shooting, game designer Charlie Cleveland had a goal: he wanted to make a game that wasn’t built around guns and combat. The underwater exploration game he and the folks at Unknown Worlds Entertainment eventually built is a sleeper masterpiece—a game that manages to evoke awe and wonder while also not really requiring you to kill anything.

But getting from prototype to release took years of iterating, including an Early Access period for pulling in lots of player feedback. Cleveland’s core idea was to build a game focused on what he calls “the thrill of the unknown”—created by giving players a seemingly depthless underwater world to explore and by filling that world with wonder and mysteries and “creatures” rather than “monsters.” Cleveland names fellow designer Jenova Chen (of Flower and Journey fame) as a source of inspiration for Subnautica’s emotionally driven design, and those influences are definitely visible in the way the game calmly and cooly reveals its secrets to players.

“It wasn’t missing combat—it was missing excitement”

It seems perhaps a little silly to not have any guns in a survival/crafting game where the player is shipwrecked on an alien world (and, indeed, there are some gun-like tools that the player can eventually wield, including a stasis rifle that freezes creatures), but making it work required building an engaging world that gave players plenty to do. Being engaged turned out to be a lot more important than being engaged in combat, and so as the game iterated through design and Early Access, the developers came up with tons of extra bits to keep players busy.

Excitement turned out to be key to solving the “how do we make a game with no guns” riddle. The player is put into a position of not being the biggest, baddest apex predator on the block (Cleveland describes humans as being about in the middle of the food chain in the world of Subnautica). The game induces tension in the player both by emphasizing the unknown nature of the world around them and also by giving players some limited ability to evade detection by giant nasty underwater beasties. Hunkering down and hiding from detection evokes the emotional tone of classic underwater thrillers like Das Boot and The Hunt for Red October—except it’s not an enemy sub out there. It’s an enormous horned leviathan monster.

The blue, the fresh, the ever free

Humans have anthropomorphized the ocean to one extent or another for about as long as humans have been around. The sea is intertwined with our nature and has shaped the path of a whole mess of different cultures on Earth, after all. Cleveland couldn’t have picked a better environment for a survival-horror game—even early creature-free prototypes with placeholder graphics managed to be fun. “You get so much for ‘free,’ just being underwater,” he acknowledged.

Subnautica winds up being something of a blank canvas. Rather than bringing with it its own extrinsic motivations for players to take up—things like points, or loot, or levels, or killing piles of enemies to get experience points—it presents a world and some vague goals and allows players to make up their own intrinsic motivations. In replacing “combat” with “excitement,” Unknown Worlds created something very special.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1517011