A team of archaeologists and its trusty drone are revealing an island community that once supplied valuable beads to the inland towns of the Mississippian culture, which thrived in the eastern United States from 800 to about 1600 CE.

The supply end of an ancient trade network

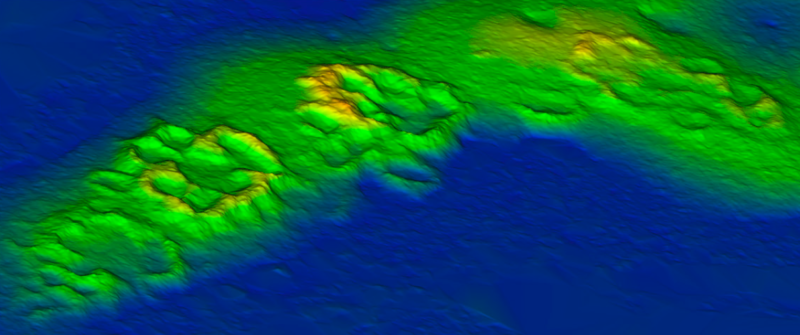

A drone armed with laser beams discovered the remains of a long-lost culture on Raleigh Island, off the north coast of Florida. The high-resolution aerial laser scans mapped a massive complex of 37 oyster-shell rings, 23m to 136m across—the kind of rings that build up around coastal settlements through years of people eating oysters and discarding the shells. Some of the rings stood less than a meter high, but others loomed four meters above their surroundings. They formed four cloverleaf-shaped clusters, each with between six and 12 shell rings arranged around the one in the center.

“Given the general size and shape of the shell rings, we suspect each was the locus of a house and household of five to eight people each,” University of Florida archaeologist Kenneth Sassaman told Ars Technica. Assuming all the rings were used at about the same time, that means 200 or 300 people once lived on the long, low-lying 30-hectare island—and it looks like every household on the island was involved in making beads from lightning whelk shells.

The shapes emerging from beneath the dense tree cover of Raleigh Island looked like an Archaic Period (between 8000 and 3500 BCE) settlement. But when Sassaman, archaeologist Terry Barbour (also of the University of Florida), and their colleagues visited the low-lying island to dig some test pits, the settlement turned out to be much more recent. Wood charcoal from the open spaces in the center of each ring dated to between 900 and 1200 CE, and potsherds from the same pits matched a style common at the same time. Life in the shell-ring settlement may have been what Barbour and his colleagues call “a reinvented tradition.”

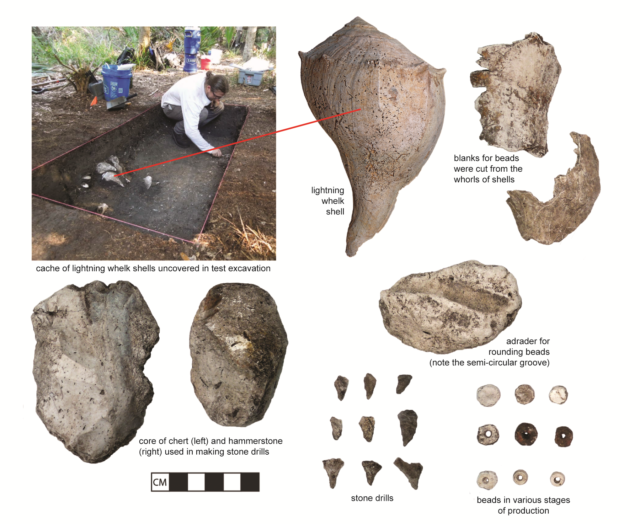

Digging in the open spaces, Barbour and his colleagues found the long-buried refuse of day-to-day life in layers 60 to 70cm deep: potsherds, charcoal, oyster and clam shells, and fish bones. Buried traces of pits and postholes suggest the presence of ancient houses but may also mark where racks or other structures once stood. Mingled with all of it, Barbour and his colleagues found traces of shell bead making on an impressive scale: bits of shell debris from bead-making, stone drills and abrading tools for shaping beads, and beads in various stages of production, from pieces of lightning whelk shell to drilled, nearly complete beads.

Based on just ten test pits so far, Barbour and his colleagues can’t yet estimate how many beads would have been produced on Raleigh Island, but “output was high, and the occupants of all the rings participated in production,” they wrote.

The pre-Columbian bead business was booming

So where were all these beads bound for? By around 800 or 900 CE, beads made of seashells had become symbols of power and status at large cities as far inland as Cahokia in present-day Illinois. Shell cups, throat coverings called gorgets, and beads in a variety of shapes were worn as jewelry or sewn onto clothing. The beads became important exchange items for a network of cities and towns spanning most of what is now the Eastern US.

Most of the popular disc- and tube-shaped beads came from a Gulf of Mexico mollusk called the lightning whelk. The demand was massive; even smaller towns, out on the political and economic periphery, could use tens of thousands of shells.

Raleigh Island may have gotten into that market on the ground floor. Artifacts from the island community date to the early years of Mississippian culture, so these coastal people may have supplied beads to the first budding chiefdoms before the turn of the 11th century. In fact, Barbour and his colleagues suggest that “entrepreneurs” from places like Raleigh Island could have helped stimulate that trade economy in the first place. And as demand increased, so did the islanders’ production of shells and beads.

Even at the height of the chiefdoms’ power, Raleigh Island was at the very edge of its political reach, so the islanders probably maintained their independence from the pre-Columbian command economy. In fact, the partially crafted shell beads at Raleigh Island suggest that people there probably weren’t trading with the biggest Mississippian cities at all. Chiefs in places like Cahokia and Etowah usually imported raw shell, not beads, and set their own craftspeople to work making beads of their own designs.

“At these large mound centers, importing whole, raw lightning whelk shell and crafting it into ceremonial cups, pendants, beads, etc. seems to have been done in order to maintain a level of control over the process of making and distributing the items themselves,” Barbour told Ars. “It is also very likely that the process of making some of these shell objects themselves carried spiritual and religious prescriptions and connotations that meant the individual needed to be a specialist or priest.” He added, “By controlling the process of making shell objects, beads included, elites could control certain meanings and narratives surrounding beads and other objects that they were producing.”

But although archaeologists don’t yet have enough data to say for sure, it looks as if some smaller cities and towns may have imported pre-made shell beads, like the ones from Raleigh Island. At the moment, we have no way to know whether Raleigh Island and communities like it also exported raw shell. We also don’t know how those trade relationships worked and what they received in return. That’s work for future excavations.

Back to the island, with more questions to answer

We know that from about 800 to 1600 CE, large networks of trade and political influence stretched across the eastern half of North America, connecting small coastal communities to large cities like Cahokia. But until now, we’ve only been able to see the big picture—not how individuals or households interacted with those sprawling regional networks. It’s a little like knowing that the Internet exists, but not knowing who makes the cat videos, or how.

Until Raleigh Island, archaeologists had never found a complex of shell-ringed living spaces like this one from the Mississippian culture. Now, the island offers a chance for archaeologists to learn about the layout of a coastal settlement—where people lived, where they worked, and where they gathered for public activities. At the moment, it looks like bead production happened in households, but more questions remain to be answered, and Barbour plans to collect more samples from each household ring on the island to look for answers.

One question is whether each household made its own beads from start to finish, in which case Barbour will probably find the full range of tools and shell debris at every household. If each house was its own bead factory, they might (or might not) have been competing with each other for trade, so archaeologists might find evidence of people experimenting with different tools and methods in order to ramp up production.

On the other hand, perhaps the households of Raleigh Island had divided up the work, with each household working on a different step of the process. “For example, some households may have specialized in removing blanks from shells, others drilling holes, and yet others doing the final shaping of drilled blanks into beads,” Sassaman told Ars. If so, the community’s leaders probably had some kind of centralized control over bead-making for trade, and Barbour will probably find different sets of shell debris and tools at each household site.

PNAS, 2019. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1911285116 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1595769