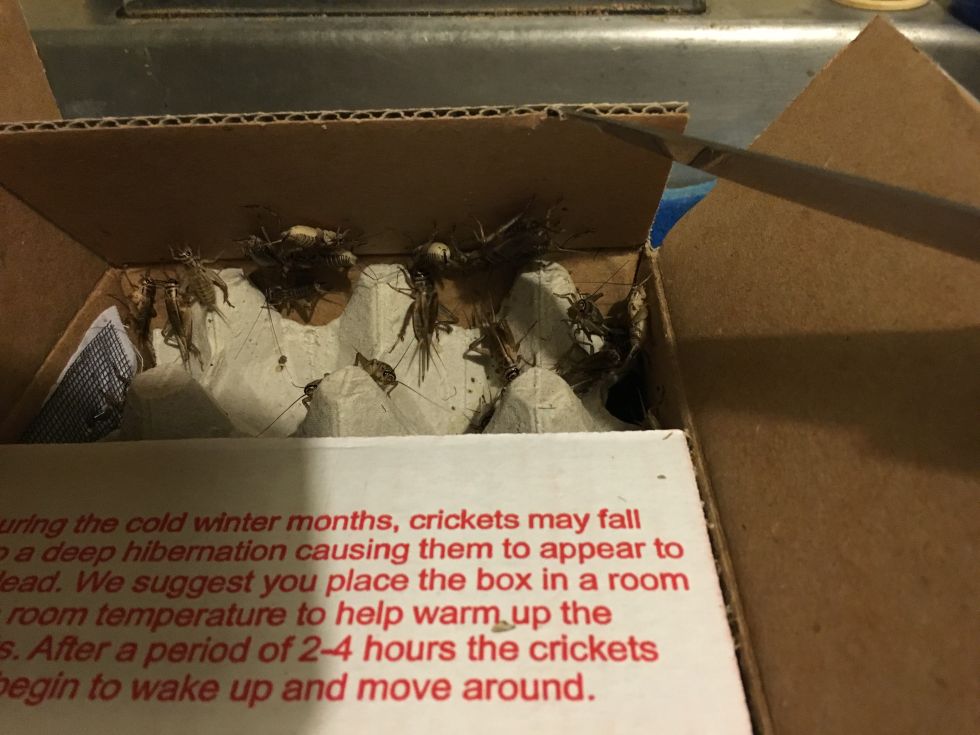

The boxes at my door were plastered with red drawings of bugs and the blunt warning: “Live Insects.” I could hear audible scratching and shuffling—and even what I thought was an errant “chirp”—as I placed them on my kitchen counter.

I slowly opened the first lid. Out poked two antennae, followed by the head of a cricket. I lifted the lid higher and saw dozens of them hopping around. Inside the second box, a thousand mealworms wriggled over an egg crate.

The first ingredients for my dinner party had arrived. Gagging slightly, I moved the boxes to my fridge.

In Western culture, eating insects is most commonly treated more like a stunt than a trend. Think of the dares on Fear Factor or of the gross-out twist in Snowpiercer when the poor find out they’ve been fed smashed insects. In other countries, however, insects aren’t uncommon in tacos or stir fry; sometimes they’re eaten straight out of the bag like potato chips.

“We have in Europe and North America a culture that leads to a lawsuit when you find an insect part in food. It’s ridiculous,” said Tom Turpin, a professor of entomology at Purdue University and a bug chef.

But slowly, entomophagy—eating insects—is catching on. In a 2013 report, the United Nations recognized that, given the food demands of a booming population, insects presented a “significant opportunity.” High in protein but with a small carbon footprint, insects seem like a “superfood’ at a time of increasing scrutiny on the sustainability of the food chain.

In the US today, protein bars and cookies can be baked with cricket flour. High-end chefs like Jose Andres and Rene Redzepi serve up grasshoppers and ants. It may soon be possible to keep a small bug farm in your kitchen, fed only by food waste—and then empty the critters directly into a pan for dinner.

Of course, all this progress continues to run into one small problem: bugs give people the creeps. So to cross that psychological barrier and embrace the food of the future, the recipe is clear. I would make a bug-based dinner of my own and actually convince my friends to eat it.

The first hurdle

I already had a passing familiarity with entomography thanks to Exo, a line of protein bars made with ground-up cricket flour that helped fuel several months of marathon training. My bug-based dinner party would have to go much further than that—we’ll get to those live mealworms in a bit—but cricket flour seemed a good place to start.

It turns out this is exactly what the bar’s creators had in mind.

“If the idea of consuming insects is a challenge already, we need to get [people] over the hurdle in a form that’s recognizable and approachable,” said Kyle Connaughton, a California chef and Exo’s head of R&D.

Connaughton first worked with insects while at England’s Fat Duck, which hosted a Victorian dinner featuring roasted crickets injected with sauces. That’s not exactly mainstream, but a protein bar is already a regular part of many people’s lives.

Exo chose deliberately non-exotic flavors for its bars, things like peanut butter and jelly or cocoa nut. The packaging emphasizes just how much protein each bar contains: 40 crickets’ worth. Each cricket has about twice the protein, by percentage, as beef jerky and just under three times that of chicken.

Crickets have been described as the “chicken of the bug world”—ubiquitous, easy to cook, providing a good base for other flavors. Since crickets are a popular pet food, the infrastructure for mass production already exists, though not every farm raises food-grade crickets (that is, grown in a manner safe for human consumption and big enough to make them worthwhile).

As an added bonus, Connaughton said, the protein from cricket flour just tastes better than conventional whey or soy protein, which is usually masked with sugary vanilla or fake chocolate. Crickets have an earthy flavor on their own, but Connaughton said that roasting and drying them before grinding brings out “reactive flavors” that deepen the flour’s taste (like the difference between a roast chicken and a boiled one).

Decades ago, sushi was popular in Japan, but it just wouldn’t catch on in America—until a Los Angeles restaurant wrapped up crab and avocado and called it a “California roll.” Exo hopes that cricket bars can do the same for bugs.

If protein bars aren’t your thing, cricket flour is expanding into more foods. Bitty, a New York-based retailer, now offers up cookies and biscuits made with cricket flour. Portland, Oregon-based Cricket Flours sells oatmeal blends with crickets and has partnered with the chain Wayback Burgers to sell a cricket chocolate milkshake.

Considering all this, cricket flour felt like a good way to ease my dinner party guests into the meal. I ordered a box of Exo bars and a bag of cricket flour from Bitty, which promised that it could be swapped into any baked-good recipe. I added both to my growing list of ingredients.

Listing image by Jason Plautz

https://arstechnica.com/?p=836591