Few people these days are familiar with the name Vannevar Bush, an engineer who played a significant role in fostering the developing of key technologies that helped the Allied Forces win World War II. He also spearheaded a highly influential federal report, Science: The Endless Frontier. Presented to President Franklin Roosevelt in 1945, the report famously argued for federal funding of basic research in science, calling it “the pacemaker of technological progress.” It shaped national science policy in the US for decades, and helped usher in an unprecedented explosion of economy-boosting scientific and technological innovation. (On the downside, Bush took a very dim view of the humanities—including science history—and social sciences.)

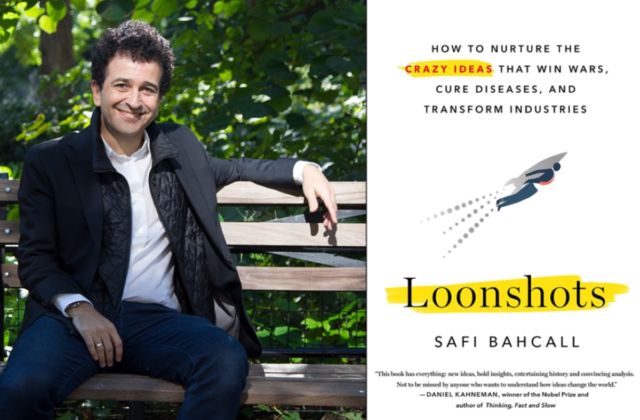

Physicist Safi Bahcall first learned about Vannevar Bush when he joined the President’s Council of Advisers on Science Technology in 2011, charged with producing a version of that 1945 report for the 21st century. The experience dovetailed nicely with his longstanding interest in the arc of human thought over the course of history, and his background as both a physicist and a biotech entrepreneur. (Bahcall comes by his physics bona fides naturally: his father is the late John Bahcall, best known for helping to solve the solar neutrino problem.) The result: an intriguing new theory about fostering innovation, based on the physics of phase transitions, that led to his first popular science book: Loonshots: How To Nurture the Crazy Ideas that Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries.

“I think business people are really tired of the thousands of more or less identical business books produced every year, saying more of less the same stuff,” Bahcall told Ars about his fresh approach to the topic. “And most economists have never seen the inside of a real company, so their models have no connection to reality. I happen to be in the middle of a very weird Venn Diagram of someone with condensed matter physics experience, someone with business experience, someone who likes to tell stories, and likes to think about history.”

According to Bahcall, the most significant breakthroughs comes from what he calls “loonshots,” as opposed to “franchises”: ideas that seem a bit crazy and are hence often dismissed outright, with anyone championing it labeled unhinged. There are two types. An S-type loonshot introduces a novel strategy or business model that no one believes can ever make money. When Sam Walton founded Walmart in 1962, for instance, he did so in a small town far away from major cities, bucking conventional thinking about the best locations for major retail. Walmart is now the largest corporation in the world by revenue, per the Fortune Global 500 list.

A P-type loonshot introduces a new product or technology that nobody believes will work. Business leaders once thought the telephone was little more than a toy, and foolishly passed on investing in what would become the Bell Telephone Company. Similarly, physicist Robert H. Goddard‘s design for a liquid-fuel rocket in the 1920s was dismissed by academic and military experts at the time. Decades later, his invention helped usher in the era of spaceflight.

Understanding the science of phase transitions can nurture loonshots faster and better, according to Bahcall, so groups can achieve a harmonious balance between radical innovation (loonshots) and “operational excellence” (stable franchises). Instead of trying to change corporate culture, he maintains that small changes in structure can help transform group behavior, much like making tiny structural changes in a material can change its phase (water freezes into ice, or boils away as vapor). That was the secret to Vannevar Bush’s success: US military culture was resistant to taking risks on radical new ideas, so instead of trying to change the culture, he changed the structure, creating a separate research branch (eventually leading to the establishment of DARPA), where those radical “high risk, high gain” ideas could find a home.

Bahcall’s theory rests on three fundamental concepts familiar to any condensed matter physicist: phase separation, dynamic equilibrium, and critical mass. No two phases can co-exist in an organization—say, being good at loonshots (eg, original independent films) versus excelling at franchises (eg the Marvel Cinematic Universe)—unless they are poised right at the critical edge of a phase transition. “At the cusp of a phase transition, blocks of ice co-exist with pockets of liquid,” he writes. The phases break apart but stay connected, cycling back and forth to maintain a state of dynamic equilibrium—teetering on the edge of chaos. Ars sat down with Bahcall to learn a bit more about his intriguing new theory.

Ars Technica: Most people associate the critical threshold of a phase transition with Malcolm Gladwell’s 2000 bestseller The Tipping Point. How does your book differ from Gladwell’s take, almost 20 years later?

Bahcall: The Tipping Point is simply a qualitative discussion of the concept that the spread of ideas is governed by a phase transition. That’s well known in the literature, and [Gladwell’s book] weaves popular stories around the concept that the spread of ideas is like the spread of a virus. Gladwell pioneered the idea of translating academic science through compelling personal stories for a popular audience. That field, which was N=1 when he did it, is now N=5,000 people imitating him.

But there’s no underlying new theory there. Loonshots is written by a scientist, and it’s based on an underlying original theory that hasn’t existed in the world of economics. No one has ever suggested the concept of an organization having a phase transition based on underlying incentives. People have been working on this problem literally for 200 years, since Adam Smith first asked, “Well, how might incentives affect behavior in organizations?” There’s a straightforward underlying academic paper I could write, which is essentially appendix B of the book. Here’s the model. Here’s why it’s reasonable. Here’s why I’m making these approximations, and here’s how you analyze this model. And here’s what you extract from it.

Ars: Let’s talk a moment about “disruptive innovation” versus “loonshots,” because you draw a distinction between these two concepts.

Bahcall: So many people are sick of hearing about disruptive innovation. The flaw with that is that it’s a hindsight problem. Disruptive innovation is all about the effects of something on a market. If you’re talking about a new idea, the market might be two years, five years, ten years, or 20 years away. The even bigger flaw is that if it’s a very early stage idea, any experienced entrepreneur knows you have no idea where it’s going to be not only a year from now, but even next week. It could morph into something totally different. So you talk about disruptive innovation to analyze history. Otherwise, we should rip that word out of the dictionary.

A loonshot is about testing an embedded belief, those things that you are sure—as a manager, or a business leader running any kind of group—are absolutely true about your world, your market, your products. But what if you’re wrong? Do you want to hear about that new idea about as much as a bullet coming at your head, or do you want to nurture loonshots to challenge your beliefs?

Ars: How does the concept of phase transitions in physics translate into a viable model for human organizations?

Bahcall: The underlying idea is that there are phases of human organization driven by the underlying interactions. So whenever you organize people into a group, the only precondition you need is that there is a mission for that group and a reward system, meaning an incentive system tied to that mission.

It can seem to a general audience to be a little crazy. How could you possibly apply physics to people? But it really is no different than economics. A market is just people interacting with incentives. The buyers want to get the lowest price, and the sellers want to get the highest price. Those are the interaction rules. The laws of supply and demand, or the “invisible hand” of the market, emerge simply from those rules. I’m just taking economics and applying it to a different system: an organization.

“The underlying idea is that there are phases of human organization driven by the underlying interactions.”

If you’re interacting within an organization, it’s not buyers and sellers, it’s employees and managers. And instead of buying and selling goods, wanting higher or lower prices, they want to maximize their incentives, their reward systems. It’s really the intersection of three things: organizational behavior, economics, and physics. Physics is only brought in as a way of thinking about collective behavior in language that economists don’t usually think about. Ultimately this is a sub discipline of economics, organizational economics, which is understanding the influence of incentives inside an organization.

The tools, or techniques, of phase transitions are a simple set of shortcuts to extract useful insights from a system. You have people in this construct of an organization. You make a simple model. The goal is to make a model that keeps it simple, but not simplistic. You want to capture enough of the underlying interaction so that you can probe the features of the system you’re interested in, but not so much that the problem becomes intractable. So that’s what I did. I found a not very complicated model of an organization and the incentives inside of an organization that was tractable.

Ars: Can you explain how organizational structure changes and a phase transition might occur as a company grows in size?

Bahcall: Whenever you organize people into a group you instantly create two forces on any individual member of that group. One is their stake in the outcome of the project that they’re working on. And the other is the perks of rank within the hierarchy. So if you’re a two-person group, let’s say each person has 50 percent stake in the outcome. Whether you call A, or B, the captain, and the co-captain, is irrelevant. If the project works, everybody is happy, and if it fails, they’re depressed and unemployed. With four people, you’re now at 25 percent stake. You’re probably going to have a team captain and three team members, but it still doesn’t matter very much.

But when you’ve a hundred people, your stake becomes, let’s say, 1 percent. You can’t have one person with 99 people reporting to them. That just doesn’t work. So you have one CEO, five VPs, 25 SVPs, and the rest are the associates or worker bees. Now, if your stake is 1 percent, what’s your reward for getting promoted? It’s probably more than 1 percent. All of a sudden we’ve had a shift. Somewhere between four and a hundred, there is a shift in balance between these two forces.

That’s the phase transition. That’s the qualitative aspect. You can write down what that looks like more mathematically, with realistic incentives. You get cash: that’s how much your base salary goes up in the hierarchy. And you get equity. That’s your stake. You write those two terms down, and then you see what the break even point is, where the derivative is zero. That gives you the equivalent of the critical point. It also tells you what controls that size. Those are the dials that you can adjust. By cranking up the size, you’re effectively making a more innovative group.

Ars: You also talk about how having a “system mindset,” versus an “outcome mindset,” can help an organization maintain the balance between radical innovation and operational excellence.

Bahcall: I took that idea from one of [chess grandmaster] Gary Kasparov‘s books. The process that helped him achieve world champion status is that, when he lost a game, he wouldn’t just analyze why a particular move was a bad one. That’s an outcome strategy. Why did my outcome not achieve what I wanted? A more interesting level is one step up, where you look at the process behind the decision. Why did you make that decision? What set of rules were you following?? That has leverage far beyond that one move. It could apply to hundreds or thousands of games in the future.

Now let’s translate that to teams, groups, or companies. A team launches a product. The product flops in the marketplace. Some teams will say, “All right, let’s sit down and figure out what happened here,” post mortem. “Well, this product didn’t have this feature. Our competitor clearly had that feature. It was superior. So let’s make sure next time we launch a product we look at these features and we don’t launch until it’s at least as good as our competitor.” That’s the lazy, lower level, outcome mindset.

The more sophisticated meta level is, how did we as a group arrive at the decision? If you use that as an opportunity to analyze your decision-making system inside a company, you can gain far more leverage. If you want to maintain this delicate balance between loonshots and franchises, you want to understand the process by which you make those decisions. Key to the success of that system is maintaining life at the edge—maintaining balance between these two groups. To maintain life on the edge, on the cusp of the phase transition, you need to be constantly probing your system.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1507555