Social perception bias is best defined as the all-too-human tendency to assume that everyone else holds the same opinions and values as we do. That bias might, for instance, lead us to over- or under-estimate the size and influence of an opposing group. It tends to be especially pronounced when it comes to contentious polarizing issues like race, gun control, abortion, or national elections.

Researchers have long attributed this and other well-known cognitive biases to innate flaws in individual human thought processes. But according to a paper published last year in Nature Human Behaviour, social perception bias might best be viewed as an emergent property of our social networks. This research, in turn, could lead to effective strategies to counter that bias by diversifying social networks.

“There’s a fundamental question about how people perceive their environment in an unequal society,” said co-author Eun Lee, a network scientist based at the University of North Carolina. Her interest in the topic was piqued in the wake of the 2016 US election and the mass protests and subsequent impeachment of the president in her native South Korea that same year. “Both sides had been separated into two groups by each issue,” Lee wrote in an accompanying Nature essay. “At the time, I was studying topics related to opinion dynamics models and wondered what was leading these collective segregation behaviors. It seemed the tendency of hearing from like-minded people trapped them in their own opinions.”

“There’s a fundamental question about how people perceive their environment in an unequal society.”

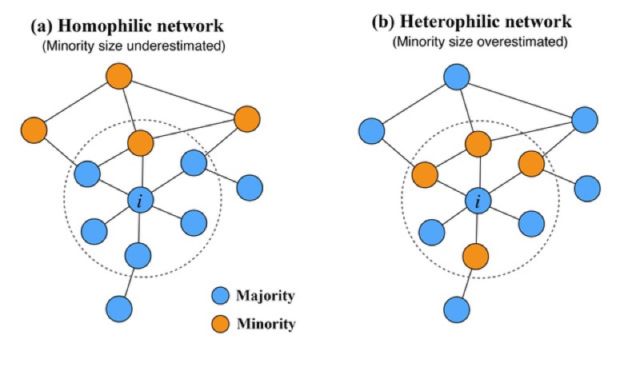

Lee had made the acquaintance of co-author Fariba Karimi of GESIS, in Germany, earlier that year at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. The two decided to collaborate on a study of the effect of “homophily“—people’s tendency to hang out with those who are similar to them (think “birds of a feather flock together”)—on people’s perceptions using network models. They came up with a generic binary model dividing individual nodes into two groups: Democrat or Republican, smoking or non-smoking, male or female, immigrants or nonimmigrants, for example.

The model treated people as individual nodes in a network, with no consideration of human cognitive processes. The emergence of perception biases depended solely on the relative sizes of the majority and minority groups, and the extent to which like nodes connected to other like nodes. To test the predictions of their model, they collaborated with co-author Mirta Galesic, who leads the research group on human social dynamics at SFI. The team conducted a survey of 300 participants based in Germany, the US, and South Korea, asking about perceptions of specific minority-associated attributes.

The team was surprised to find that the survey results closely matched the model’s predictions. Specifically, “People who were surrounded by people similar to them think that their group is larger than it really is, and people who have more diverse social circles think their group is smaller than it really is,” Galesic told Ars. “These biases are exaggerated with the relative size of the majority and minority groups.”

Thus, social perception bias appears to be a basic property of social networks (and large-scale networks in general), similar to the famous “six degrees of separation” phenomenon, or small world network structure, whereby everyone is separated by six or less social connections.

One future research angle might be to merge the current work with another model the group devised for how people recall information from memory. “We are immersed every day in experiences with different people and this leaves traces in our memory,” Galesic explained. “When we are asked to make judgments [like those in the study], we are basically trying to recall what we experienced and make a more or less precise judgment.”

There are so many different kinds of cognitive biases, each with its own unique working hypothesis about why such a bias flourishes and how best to combat it. But the implications of the SFI study is that perhaps the explanation is much simpler. “It’s basically just what our social network serves us as information, which is then reflected in our memory and is used to make social judgements,” said Galesic. “Then the solution is to enable people to meet as many different people as possible, to broaden their social horizons.”

The sticking point: people often strenuously resist such diversification efforts, in part because the associated cognitive dissonance can be so extreme and uncomfortable. “My personal opinion is that this is not an individual property,” said Galesic. “Most of us are just trying to fit in with the people we need to collaborate with, who are around us in a particular environment. I don’t think that people are inherently closed-minded. So a lot of that can be changed by changing the social environment.”

This is easier said than done. But tweaks to city design and media ecosystems to make them less sharply segregated might be a good start. For instance, Galesic acknowledges that while she lives in the fairly liberal city of Santa Fe, her social circle is comprised almost entirely of white intellectuals, even though the city is also home to a large population of Hispanic people and Native Americans. She only interacts with those groups once a year at the annual city festival.

The same might hold true for scientific collaborations comprised solely of women (who remain a minority group in many physical sciences). It’s a troubling paradox, since the same support structure that helps women cope with isolation can, in turn, exacerbate it. “When we have a minority group, and this minority is so cohesive as to only interact among themselves, they lose their overall visibility to the majority,” Karimi told Ars. “This is disadvantageous, but on the other hand, people need in-group support in order to thrive in academic workplaces.” The trick is to find a balance between the two extremes.

There is no easy answer when it comes to implementing structural changes that encourage diversity, but today’s extreme polarization need not become a permanent characteristic of our cultural landscape. “I think we need to adopt new skills as we are transitioning into a more complex, more globalized, and more interconnected world, where each of us can affect far-away parts of the world with our actions,” said Galesic. “We need to learn not to close ourselves off with the same circle of friends, but instead to intentionally communicate and go talk to other people.”

And if you cannot change the system, try changing your personal social network to counter your own social perception bias. “For a society, systematic social changes, including an increase in the number of minorities and getting more opportunities of knowing minorities, might help us live with more accurate perception,” Lee wrote. “I think it can be a light in this period of conflicts between minorities and majorities.”

DOI: Nature Human Behaviour, 2019. 10.1038/s41562-019-0677-4 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1637509