We’re reaching the end of summer in the Northern Hemisphere, and the weather in the US has been about as eventful as one expects for the year 2020. A highly active Atlantic hurricane season has lived up to expectations so far, while record-setting wildfires have blanketed the drought-beset West Coast, creating smoke that has drifted clear across the country.

NOAA’s latest monthly summary shows how all this developed in August and what we have to look forward to in the next three months. Critically, La Niña conditions in the Pacific seem to have settled in, which has implications for winter patterns across North America and beyond.

Looking back

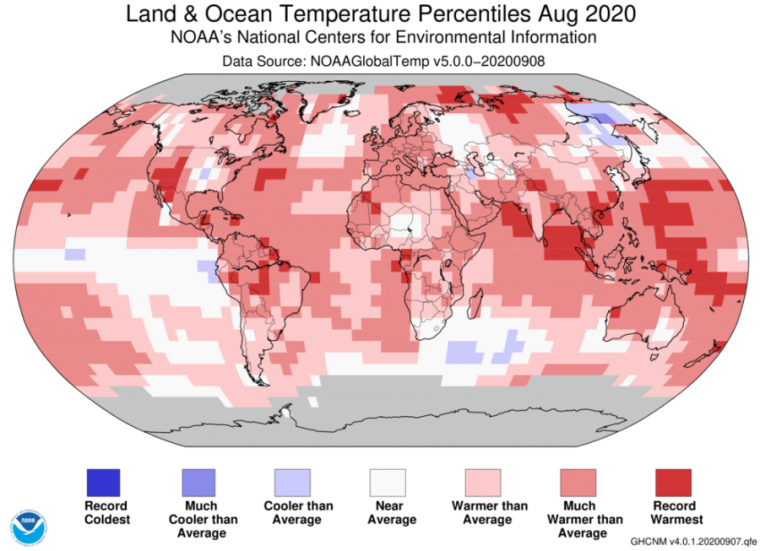

Globally, this was the second-warmest August on record (going back to 1880) and the third-warmest June-August stretch. Looking at the entire year through August, 2020 is the second-warmest on record just behind 2016. With so little of the year left, it’s very unlikely to drop in the rankings, and it still has a chance at the top spot. NOAA currently puts the odds of a new record at about 40 percent, while other estimates continue to be a bit higher. La Niña conditions will hold down the global average, so topping 2016 and its warm El Niño would be remarkable.

August in the contiguous US fell in line with the global numbers, coming in at third warmest. California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado each set a new record for their warmest August, as a high pressure system over the region produced a notable heatwave in the third week of the month. (This included a mark of 130°F/54ºC measured in Death Valley.) This particular pressure pattern is more common with a La Niña.

While August saw wet conditions in parts of the Eastern US—partly connected to hurricanes—it was exceptionally dry in much of the West. As a result, the area of the contiguous US in drought ticked up a couple more percentage points to about 39 percent. This includes most of the West, but also New England and portions of the Midwest.

-

August comes in second-warmest for the globe.

-

State temperature rankings for August, where 126 is a record.

-

For June through August, some regions ended up near average, but the rest were warmer.

-

Much of the country—and pretty much the entire West—got below-average rainfall in August.

-

The story is similar for the June-through-August total.

-

About 39 percent of the contiguous US is now in drought.

-

Here are the wind speeds experienced during the August 10 derecho.

NOAA tracks the number of weather-related disasters that exceed $1 billion in damages, and 2020 is on pace to be one of the worst years by this measure. August contributed several of those disasters.

August 3 saw Hurricane Isaias make landfall in North Carolina as a Category 1 storm. But from there, it spun its way up the East Coast, spawning dozens of tornadoes, including several EF-2 and an EF-3 twister.

On August 10, a derecho thunderstorm line raced across the Midwest, producing straight-line winds exceeding 100 miles per hour in some areas and 15 weak (EF-0 to EF-1) tornadoes. Iowa was hardest hit, with over 40 percent of its croplands damaged by winds.

In mid-August, a peculiar storm system brought prolific lightning to California with little accompanying rain, sparking dozens of wildfires that have since merged into several massive complexes. The August Complex fire is now the largest fire in California’s record, which goes back to 1932. The LNU Lightning Complex fire became the second largest on record. The SCU Lightning Complex fire is the third. The latter two are now almost completely contained, but the August Complex is still at only 30-percent containment. (Oregon and Washington added their own major wildfires in September, as wind conditions worsened across all three states.)

And on August 27, Hurricane Laura made landfall in the Gulf of Mexico at Category 4 strength. NOAA notes this was the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana since 1861, and the state has sustained significant damage to the electrical grid and water infrastructure.

Looking ahead

After largely being stuck in neutral since 2016, the Pacific has shifted to a La Niña pattern, which means cooler water has risen to the surface along the equator in the eastern half of that ocean basin. That shifts pressure patterns around, loading the dice for some regional temperature and precipitation averages. NOAA’s forecast gives the La Niña 75-percent odds of persisting through the winter, and it’s also the most likely forecast for the spring.

Particularly in the winter season, La Niñas tend to hold the jet stream in a position that brings cooler, wetter weather across the Northern US, but drier and warmer weather across the South—particularly throughout the Gulf region.

NOAA’s one-month and three-month outlooks are based on patterns like that La Niña, long-range weather model simulations, and observed long-term trends (like human-caused warming). In both time windows, the outlook calls for temperatures above the 1971-2000 average for nearly all of the US. Precipitation is more varied, though, with odds leaning toward above-average rain for the Pacific Northwest and coastal Southeast (where hurricane season continues). But dry weather is favored across a broad swath from the Southwest to the Central Plains states.

That means that the Pacific Northwest and New England (and Hawaii) are the only regions that are likely to see some improvement in drought. Drought is expected to expand in Southern California, across much of Texas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska, as well as in Alabama.

North of the border (we have heard your requests, Canadian readers), the three-month outlook also primarily calls for temperatures warmer than the 1981-2010 average. Wetter weather is generally favored for British Columbia and across the northern half of the country, with below-average precipitation possible for portions of the Prairies and the Atlantic coast.

-

Here’s the October temperature outlook, where color shading shows probability of above/below average.

-

The three-month outlook is similarly warm.

-

Canada’s three-month outlook is also warm.

-

Here’s the October precipitation outlook, where colors represent probability favoring above/below average. (EC means “equal chances” of either.)

-

And again, not a ton of change in the three-month outlook.

-

Here’s the pattern that often sets up in La Niña winters—look familiar?

-

Three-month precipitation outlook for Canada.

-

The drought outlook is good for the PNW and New England, not so good elsewhere.

For California, an outlook of expanding drought doesn’t provide a ton of solace for those fearing the rest of the wildfire season. The explosive fire seasons of 2017 and 2018 turned ugly a little later in the year, as a late arrival of the rainy season caused a dry landscape to collide with the hot and strong Santa Ana/Diablo winds that can occur in fall and winter. Although La Niña winters generally see below-average precipitation in California, the three-month outlook doesn’t show a strong dry signal for Northern California. You can still hope for enough rain to put a damper on the late fire season.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1707579