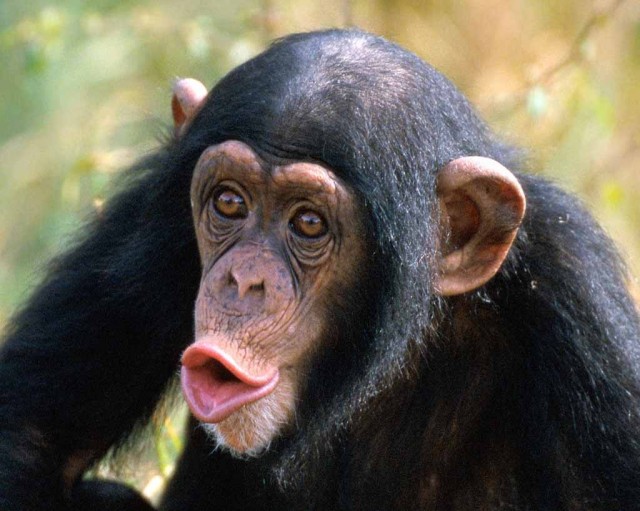

Wildlife veterinarian Stephen Ngulu starts his typical working day watching from a distance as the chimpanzees under his care eat their breakfast. He keeps an eye out for runny noses, coughing or other hints of illness.

These days, Ngulu and others at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy’s Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Kenya have doubled down on their vigilance.

Chimpanzees and other great apes—orangutans, gorillas and bonobos—are prone to many human viruses and other infections that plague people. So when SARS-CoV-2 began circulating, the community that studies and cares for great apes grew worried.

“We don’t know what will happen if the virus is transmitted to the great apes. It might get severe,” says Fabian Leendertz, an infectious-disease ecologist at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin. These endangered apes have the same receptor that SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter human cells—angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)—making infection a distinct possibility. What’s less predictable is how sick the apes might get were the virus to take hold.

Genetic similarities—we share at least 96 percent of our DNA with each great ape species—mean that apes are susceptible to many viruses and bacteria that infect human beings. And though some human pathogens (such as a coronavirus called HCoV-OC43 that causes some cases of the common cold) cause only minor illness in the animals, others can be disastrous. “There have been incidents of common human respiratory pathogens spilling into chimpanzees, and it’s fatal to them,” says Fransiska Sulistyo, an orangutan veterinary consultant in Indonesia.

Between 1999 and 2006, for example, several outbreaks of respiratory disease occurred among chimpanzees in the Ivory Coast’s Taï National Park, including a 2004 episode that infected a group of 44 and killed eight. Analyses suggest that the underlying pathogens were human respiratory syncytial virus or human metapneumovirus, which both cause respiratory illnesses in people, along with secondary bacterial infections. And in 2013, rhinovirus C, a cause of the human common cold, caused an outbreak among 56 wild chimpanzees in Uganda’s Kibale National Park, killing five.

Even in normal times, those who work at ape sanctuaries or study apes in the wild are perpetually trying to stave off disease. Guidelines from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recommend that field researchers and sanctuary staff coming from other countries quarantine for at least a week before entering ape habitat, in the wild or otherwise. They should wear face masks and stay at least seven meters away from apes. The IUCN also recommends that people working with apes stay up to date on immunizations, get screened for infectious diseases of regional concern (tuberculosis and hepatitis, for example), and watch for signs of illness in research staff. Sanctuaries should routinely disinfect surfaces within their facilities.

Such practices have been common for years, says anthropologist Michael Muehlenbein of Baylor University, who wrote about the risks of ecotourism to apes and other wild animals in the Annual Review of Anthropology. “They just now need to be applied more vigilantly.” But, he adds, the IUCN’s guidelines are only recommendations. Enforcement responsibility rests on sanctuaries and research groups.

The Sweetwaters sanctuary employs such practices, veterinarian Ngulu says. But in February 2019, he got a taste of what might happen if a virus like SARS-CoV-2 broke through. A severe respiratory outbreak—probably spread from an asymptomatic worker infected by some bacterial or viral pathogen—had affected all 39 of the sanctuary’s chimpanzees, and two died. “From that experience last year, I can say I was baptized by fire,” he says.

With the emergence of COVID-19, it was clear that Sweetwaters needed to further tighten protocols. To that end, it has closed visitor areas and suspended volunteer activities and allows only necessary staff into the sanctuary. Workers returning from leave quarantine at the staff camp for 14 days instead of immediately resuming work, then remain at the sanctuary for a month at a time, until another staff member comes to relieve them.

Measures also have tightened in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the local wildlife authority locked down a chimpanzee sanctuary called J.A.C.K. (a French acronym that stands for young animals confiscated in Katanga) from April through August. “Our team made huge sacrifices away from their families,” says Roxane Couttenier, J.A.C.K. founder and one of the sanctuary managers. “Chimpanzees are known for having fragile lungs, and because the coronavirus is brand new, it was obvious we had to protect them.”

Although staff now can go home between shifts, they take extra precautions before returning to work, like changing face masks before entering the sanctuary and traveling by foot or bicycle to avoid crowded buses.

Orangutan sanctuaries in Indonesia have also been in lockdown, says Sulistyo. They’ve limited staff on site, and those staff aren’t permitted to leave the local town. They’ve arranged the orangutans into what scientists call epidemiological groups, akin to the COVID pods that people have formed with friends and family. That way, if an orangutan becomes infected, staff can limit further spread.

Economic effects of the pandemic—a global recession, no tourism—have hit the sanctuaries hard. At Sweetwaters, staff have taken at least a 20 percent pay cut while working more hours. Ngulu says there’s less money to buy food for the chimps and disinfectants and personal protective equipment for staff. At the orangutan facilities, Sulistyo says, “they’ve had to close and cut staff,” affecting the standard of care.

The pandemic has shut down or reduced work at many field sites, slowing the pace of research, Leendertz says. In the case of his own group, which tracks pathogens circulating in nonhuman primate populations in the Ivory Coast, the bare minimum of staff is on site. “There are still people collecting data because it’s important to keep monitoring those populations,” he says.

Wherever people and great apes share a common environment, there will be a risk of exchanging pathogens, says George Omondi, former deputy manager and head veterinarian at Sweetwaters and now an epidemiologist and wildlife veterinarian researcher at the University of Minnesota. “Every sanctuary exists in the continuum of a community,” he says.

And so a growing number of experts favor what is known as a One Health approach, the better to protect all of us. Keeping local human populations healthy and tracking human diseases can prevent transmission of dangerous pathogens to apes. And monitoring disease in apes and implementing protective health measures at the reserves and sanctuaries prevent pathogens from jumping from apes to the people who work with them, and from there to the broader community.

“We cannot only focus on great ape health,” Leendertz says. “We have to look at the human population, the entire picture, while still trying to protect the great apes.”

10.1146/knowable-120220-3

Jackie Rocheleau is an independent science journalist covering brain science, public health and, if she’s lucky, cool animal stories too. Follow her on Twitter @JackieRocheleau.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews (sign up for the newsletter). It is part of Reset: The Science of Crisis & Recovery, an ongoing series exploring how the world is navigating the coronavirus pandemic, its consequences and the way forward. Reset is supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1732164