The American 19th century entrepreneur Thomas Edison is perhaps most famous for his development of the incandescent light bulb, but few people likely know that part of his inspiration came from an obscure fellow inventor in Connecticut named William Wallace. Edison visited Wallace’s workshop on September 8, 1878, to check out the latter’s prototype “arc light” system. Edison was impressed, but he thought he could improve on the system, which used a steam-powered dynamo to produce an incredibly bright light—much too bright for household use, more akin to outdoor floodlights. The result was the gentle glow of the incandescent bulb.

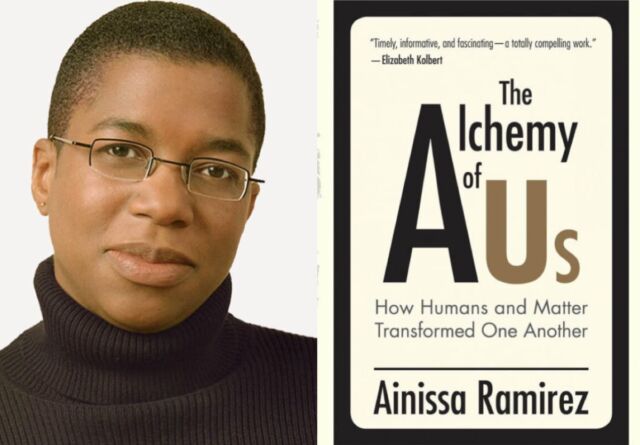

Other inventors had come up with versions of an incandescent lamp prior to Edison, but the Menlo Park wizard discovered an excellent incandescent material in carbonized bamboo that lasted for over 1000 hours, and also devised a fully integrated system of electric lighting to drive adoption of this new technology. Edison found a material he could shape to his needs. But electric lighting would in turn shape how people slept, as physicist and self-described “science evangelist” Ainissa Ramirez explains in her book, The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another, released in April.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, people experienced “segmented sleep”: they would retire to bed and sleep for three or four hours (“first sleep”), then wake up after midnight and stay awake for another hour or so, before going back to bed for their “second sleep.” There are references to first sleep in Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid, according to Ramirez, as well as several 19th century novels and thousands of 19th century newspaper reports. “When artificial lights came into being, they pushed back the darkness and lengthened the day,” she writes.

It’s just one of the many fascinating interconnected tales featured in The Alchemy of Us, which opens with the story of Elizabeth Ruth Belville, aka the Greenwich Time Lady, whose work was the means of ensuring standard time in London before the advent of radio. Bearing her pocket chronometer No. 485/786—a family heirloom dubbed “Arnold”—Belville made the rounds every day to her 200 or so clients, who would pay for the privilege of looking at Arnold (set to Greenwich Mean Time) and adjusting their own timepieces accordingly. That growing cultural obsession with keeping time also ended up impacting our sleep patterns.

Again and again, in The Alchemy of Us, Ramirez demonstrates how we shape materials, and are shaped by them in turn, whether it’s steel rails, telegraph wires, hard disks, glass, or the thin and flexible cellulose film—which eventually spawned the entire movie industry—invented by a New Jersey preacher name Hannibal Goodwin. (Goodwin died in a tragic street accident before he could capitalize on his invention, leaving the way clear for George Eastman to start production of roll-film using his own patented process.) Ars sat down with Ramirez to learn more.

Ars Technica: What inspired you to write this particular book?

Ainissa Ramirez: I was trying to find another way for people to get excited about materials. There’s a whole range of books out there that profile different materials and how they’re used, maybe telling a few stories [in the process]. I decided to turn that upside down and really focus on the story—because I believe stories are a little stickier—and use that as a conveyor belt, if you will, to have the science enter into someone’s mind. It was also an attempt to generate new myths. We talk about great people, great men of science, and I really wanted to emphasize people that you don’t know, who’ve made things that you take for granted.

Ars Technica: We have built a popular science mythology with people like Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Albert Einstein, and so forth in the pantheon. But there are all kinds of inventors and scientists lost to the archives—William Wallace doesn’t even have his own Wikipedia page—and your book brings them more to the forefront. How does it happen that some of these people get forgotten while others are lionized?

Ramirez: Well, part of Edison’s business was promoting Edison. He actually had a reporter following him all the time. He met William Wallace in Ansonia, Connecticut, which is actually two cities over from where I am. I went over there and I asked people, “Did you know Edison came to Connecticut?” Nobody knew this. Over the generations, the myth has become that he just had this bolt of inspiration, not that he got it from some gentleman tinkerer. So Wallace is often relegated to the footnotes in many Edison biographies. I got to see one of the lights Wallace had made, and the factory. There was much, much more to him than that footnote. I just wanted to give him an opportunity to shine.

Ars Technica: I understand the book’s theme came about when you signed up for a glass-blowing class. Can you tell us a little about that?

Ramirez: I live about two cities over from a glassblowing studio. I had gone to Italy and saw Murano glass makers and I was like, “Oh, my God. This is amazing.” I wanted to learn new things about an old material. When I’ve worked with materials [in the past], I was working with nanotechnology, so I had many degrees of separation between myself and the material. So I signed up for a class, but I was very, very timid, because you’re working with things that can definitely give you some harm. My instructor said, “If you step on hot glass, it’s going to melt a hole in your shoe.”

There was a physicality to it that I really enjoyed. I also was able to put concepts together with action. I could swing the glass and I was employing viscosity. The way that I rolled the glass on this metal surface spoke to heating and cooling. I was developing over the course of weeks a new relationship with glass. And then I had a very bad day where I was working with the glass and it fell on the floor. Fortunately my instructor came over and reattached the piece to my pipe. But after I completed that very lopsided looking piece, I thought, “I came into class in a very bad mood. And then I wasn’t in a bad mood.” The glass shaped me. I was certainly shaping it because it was a lump and I was giving it form.

Maybe it was a little bit of a stretch, but it made me think, “Okay. I was in a dance with this glass. Nothing else was on my mind. It was shaping me because it was putting me in a better mood.” That was the impetus for me to think about this dance between humans and matter, and how they shape each other. I kind of became a glass nerd. What I didn’t think was covered was glass’s role in science and how instrumental it’s been in terms of discovering things like the electron, and penicillin, for example.

Ars Technica: What are some of your favorite stories that you discovered while researching and writing your book?

Ramirez: I stumbled on the story of Hannibal Goodwin by accident. My brother told me, “I just heard about this guy in Newark, a preacher who made a camera film.” I said, “Stop giving me new work. I’ve got stuff to do.” But I looked into it and yes, Hannibal Goodwin had created camera film before George Eastmam. I’m originally from New Jersey, and I hate when New Jersey history gets buried. I found the people who are taking care of Hannibal Goodwin’s old home. It’s very dilapidated. In fact, you can’t walk in the center of the floor because it’s decaying. But I was able to go into his house and take a picture of where he did his experiments.

I also learned about Almon Brown Strowger, a mortician who became convinced that the operator was redirecting calls to his competitors. The story goes that he was reading the obituary section, and he was upset because his friend had died. We’re not sure whether he was more upset that his friend had died, or that his competitor had embalmed the body. It put him into a creative rage, where he wanted to figure out how to make an automated switch that didn’t require female operators, known as “Hello Girls.” He wore very nice clothes and he kept his collars in a cylindrical box. He took that out, dumped all the collars, and stuck in some pins. He thought, if I were to move something up and down, I can reach each one of these pins, and each pin could be a telephone number. If the number was 73, the pin would move over seven and up three, for example.

He applied for a patent for [the “Strowger switch“] and eventually found someone to make it. That was the first automatic exchange, and it was part of Bell Labs’ business for a long, long time. I worked at Bell Labs, but I had never heard of Almon Strowger. I only heard about him because I went to an antique radio museum—really just an old warehouse—in New Haven. I called my friend at the Bell Labs archives and said, “There was a mortician who created the switch. How come you don’t put that out in the front? Because that’s an amazing story.”

Ars Technica: The last chapter, “Think,” talks about how, even though materials, and the associated technology, is shaping us, we can and probably should push back a little, because it might in turn help us reshape technology in a more beneficial way. Can you elaborate on that point?

Ramirez: Thinking is the most human part of us. It’s already been shown that the way that we think has been altered by our devices. This has always been the case. Ancient Greek teachers used to be so angry when their students wrote stuff down because they were expected to memorize and remember those things. The computer might just be an extension of that, but the way computers are being infused into our lives, it’s happening much faster. I think we should just pause and make sure that this is the direction that we want to go in. I know my childhood phone number but I don’t know my mother’s [current] phone number because it’s stored in my smartphone. We now have a new relationship to information.

Having stuff in our memory banks is good, because in our subconscious we’re going to put them together in new ways. But if we’re just offloading them to our hard drives or to our computers, will creativity look the same? That’s the question I wanted to ask, and I used this book as a gymnasium. I’m hoping that if we look at older technologies that we think are simple, like the telegraph and the light bulb—if we can be critical of them, then when things come down the line like driverless cars and AI, we can at least feel empowered to ask questions. “Hey, the telegraph shaped language in unexpected ways. This AI thing, I have some questions.” Hopefully this book is a manual for us to look to the future, by taking another gander at the past.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1732479