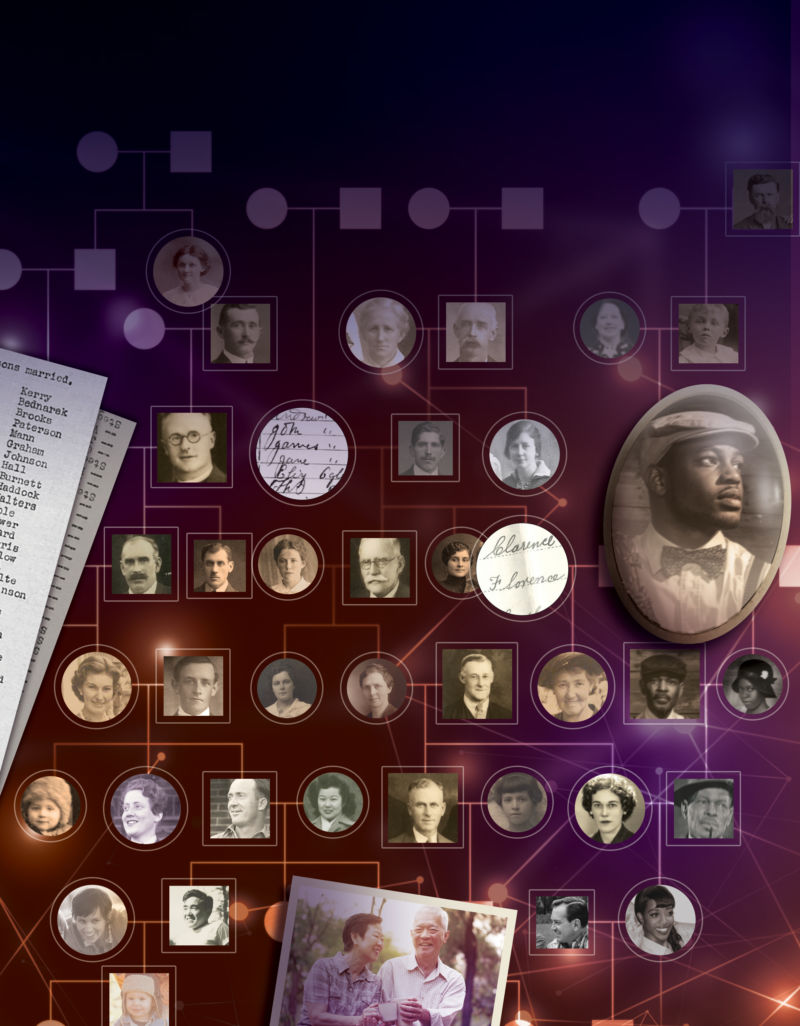

Using crowdsourced data from a social genealogy site, a team of geneticists put together a family tree that includes 13 million people. Researchers used this behemoth of a family tree to investigate how much heredity influences longevity and to track shifts in migration habits and marriage taboos in Europe and North America over the last 300 years.

Tree building

Putting together an extended family tree on such a large scale is normally a daunting and tedious task for researchers. They typically have to ferret out records from churches and county courthouses, and most of the time those records are the old-fashioned paper kind. Tracing long-distance connections using these records can be a nightmare.

But the payoff is big, because tracking that many people’s relationships can yield insights into cultural trends, economics, genetics, and population movements. That’s especially true if researchers can combine the family tree with genetic or health data for the people listed.

New York Genome Center geneticist Joanna Kaplanis and her colleagues say they’ve found an easier way to assemble the large, interconnected datasets they need: crowdsource it from popular genealogy sites. The team collected 86 million individual records from genealogy website Geni.com, a database of genealogical data uploaded and maintained by enthusiasts. Each record contains a person’s name, their connections to other people in the dataset, and other information like when and where they were born, got married, and died.

The site’s software checks whether each user’s family tree has any branches in common with other profiles, then helps merge those small family trees into larger ones. That, combined with the researchers’ analysis and processing, turned all those records into a total of 5.3 million family trees, the largest of which connected 13 million people and spanned 11 generations born between 1650 and 2000.

Mobility

Armed with that map of human connections on a massive scale, the team was able to spot some interesting patterns of migration, marriage, and longevity over time. For instance, during the whole three centuries covered by the database, women moved more often than men, but they tended to move shorter distances. Men who moved made longer moves on average than women and were much more likely to end up in a whole new country.

“One potential explanation is that males tend to stay in their home town due to better economic opportunities: maybe a shop that they inherited or land. This creates pressure, or a social norm, for females to migrate closer to the home town of their husband,” explained coauthor Yaniv Erlich, a geneticist at Columbia University. “On the other hand, when males do migrate, they migrate to a much longer distance—for example, soldiers in an army that crosses Europe, and then soldiers marry local females.”

Differences in mobility between the sexes have been a consistent trend from 1650 up until the late 20th century, according to the study data. People’s marriage habits, on the other hand, changed drastically in the 19th century. From 1650 to about 1800, the average married couple in Europe and North America were fourth cousins, and most had been born within eight kilometers of each other.

Historians have long assumed that, with the advent of railroads and steamships, people moved around more and were therefore more likely to marry people born farther from home, as well as people more distantly related to them. But this study’s data says the story is more complex than that.

People did start marrying farther from home as everyone started moving around more. The average person born in 1850 would marry someone born 19km away from their own birthplace. And by 1950, the average couple was born a whopping 100km apart.

But people born between 1800 and 1850, who would have been old enough to marry between about 1820 and 1875—just at the peak of the rapid spread of transportation technologies like railroads and steamships—actually showed a slightly increased tendency to marry relatives than their predecessors. That’s true even though the cousins they married had been born farther from their own birthplaces.

That only began to change for people born in about 1850, who were much less likely to marry a relative than earlier generations. Because of the 50-year lag between the increase in people’s mobility and their shift to marrying non-relatives, Erlich and his colleagues say the shift probably had more to do with changing cultural taboos about marrying cousins.

Long-lived genes? Maybe not

The study offers some hints that previous estimates of how much your genes impact your longevity may have given heredity a little too much credit. The researchers tracked longevity—how long a person lives compared to their expected lifespan at birth—among lineages in the sprawling family tree. Because there were so many connections, even among very distant relatives, the team was able to rule out the effects of people living in the same household and look for patterns that could be attributed to heredity.

Most studies estimate that about a quarter of the complex set of factors that determine how long we live comes down to heredity, but Kaplanis, Erlich, and their colleagues say that it may actually be closer to 16 percent.

“These results indicate that previous studies are likely to have overestimated the heritability of longevity,” they write. “As such, we should lower our expectations about our ability to predict longevity from genomic data.” We probably shouldn’t expect good odds of identifying genes directly linked to longevity, either.

While the findings are interesting, it may be more significant that the team was able to get scientifically useful datasets from popular genealogy sites. That opens a lot of doors for further studies, and Erlich says some of that work is already in progress.

“During this year that the study was under review, we collected a large DNA database of over 1 million [records]. We also have surveys where people can document different phenotypes,” he said. “All of these mean that we are not going to run out of data or research questions soon!”

Science, 2018. DOI: 10.1126/science.aam9309 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1267777