Earlier this month, the Haiku project released the second beta of its namesake operating system, Haiku.

Haiku is the reimagining of a particularly ambitious, forward-looking operating system from 1995—Be, Inc.’s BeOS. BeOS was developed to take advantage of Symmetrical Multi-Processing (SMP) hardware using techniques we take for granted today—kernel-scheduled pre-emptive multitasking, ubiquitous multithreading, and BFS—a 64-bit journaling filesystem of its very own.

BeOS—the Apple OS that never quite was

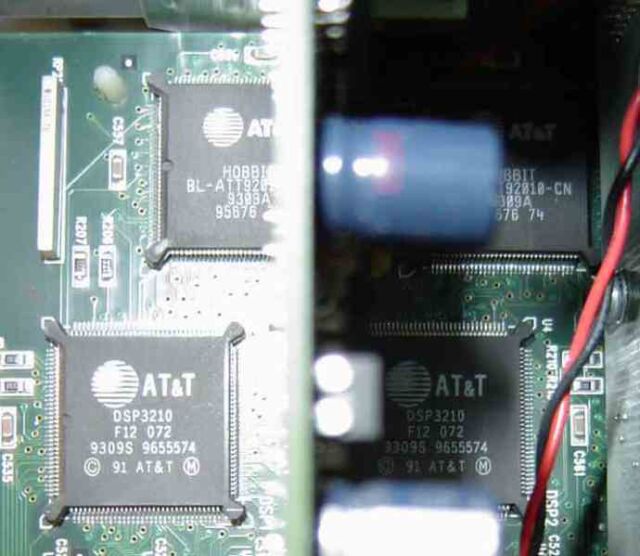

Most of those who remember BeOS remember it for its failed bid to become Apple’s premiere operating system. The platform was created by Jean Louis Gassée, a former Apple executive who wanted to continue work he had done on the discontinued Apple Jaguar project. In its early days, Be developed the machine for its own hardware, called the BeBox—a system with two AT&T Hobbit processors on which BeOS’ unrivaled attention to SMP efficiency could shine.

Unfortunately for Be, AT&T discontinued the Hobbit in 1994—a move that perhaps should have been anticipated by Gassée, given that Apple itself had originally approached AT&T to develop the Hobbit, but then abandoned it due to it being “rife with bugs… and overpriced.” In the scramble to find a new hardware platform, Be moved to PowerPC architecture. The company moved through eight hardware revisions in two years before giving up on designing its own hardware.

The next step for BeOS was Apple’s own Common Hardware Reference Platform. Apple was in dire need of a refresh for the aging MacOS Classic, and briefly the tech industry was abuzz with the possibility that BeOS would be the next Apple operating system—but Gassée and Apple’s then-CEO Gil Amelio couldn’t agree on a price. Gassée demanded $300 million, but Amelio wouldn’t go higher than $125 million. In the wake of the stalled negotiations, Apple’s board decided to bring founder Steve Jobs back into the fold by purchasing his NeXT, instead.

This was the beginning of the end for BeOS, which went through another four years looking for a home—distributed first on Power Computing’s Mac clones, then Intel x86 computers, and even a free, stripped down “Personal Edition” intended to drum up consumer interest, which could be run atop either Microsoft Windows or Linux. In 2001, the rights to BeOS were sold off to Palm, largely ending the original BeOS saga.

Although Be, Inc sold the rights to BeOS to Palm in 2001, its community had no intention of abandoning the project—it founded an OpenBeOS project the same year. In 2004, Palm sent a notification of trademark infringement regarding the name, and the project renamed itself Haiku.

Back to the present: Installing Haiku R1/Beta 2

-

You can run the Haiku installer directly, or you can run it from within the live desktop itself.Jim Salter

-

An enormous variety of partition types are available here. The choices here refer only to Type ID—not formatted filesystem.Jim Salter

-

When Haiku asks you to “initialize” a Be File System partition, what it really means is “format.” Back to the partitioner!Jim Salter

-

Right-clicking the new partition, then selecting Format->Be File System is the step we missed before.Jim Salter

-

Success! We can now click “Begin”—from here, we’re literally only a minute or so away from a fully installed Haiku system.Jim Salter

In June 2020—nineteen years after OpenBeOS was born, and sixteen after its rename to Haiku—the project released its second beta distribution. The project still adheres to backward application compatibility with 1990s BeOS—although only in its 32-bit version, which I did not test.

Haiku’s installer is easy to use, if you know what you’re doing—but that caveat is an important one. There’s a live desktop option, but I dove straight into the full hardware install in a new Haiku VM, and it was a bit frustrating.

Disk partitioning is both necessary and entirely manual. The installer tells you it will need “at least one partition [initialized] with the Be File System” but otherwise leaves you alone. Inside the partition manager, there are no hints about “Intel Partition Map” vs “GUID Partition Map”—or whether a GUID Partition Map will also need a BIOS Boot Partition.

It’s also not clear that creating a “Be File System” here really just means setting a Type ID on a raw partition and isn’t sufficient to let the installation continue. After creating the partition, you must then select it and format it—the installer won’t do it for you and won’t warn you why the installation can’t continue, either.

Once I’d figured that out, I went with a GUID partition scheme, created a 1000MiB BIOS Boot partition, allocated the rest of my 32GiB virtual drive to a BFS partition, and formatted it. The main installer stopped complaining that it couldn’t find a valid installation target, and the rest of the installation was over with in a minute or less.

Listing image by Jim Salter

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1687930