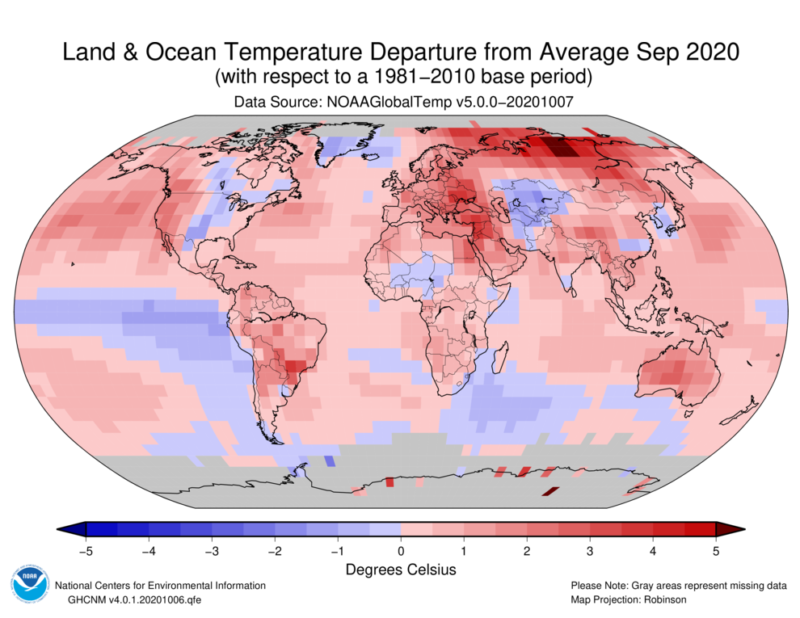

September apparently wasn’t feeling like doing anything unusual, so it ended up being the warmest September on record for the globe. That’s been something of a trend this year, with each month landing in its respective top three. It has become increasingly clear that 2020 will likely be the second warmest year on record, if it isn’t the first.

Unlike in August, the contiguous US didn’t set a record in September, though it was still above the 20th century average. A high-pressure ridge dominated over the West Coast again, leading to even more warm and dry weather for much of the Western US. But a trough set up over the Central US in mid-September, bringing cooler air southward.

Two more hurricanes—Sally and Beta—led to above-average rainfall in the Southeast. Total precipitation for the contiguous US was a touch above average as a result, but the average as usual masks local differences. Drought conditions have expanded and worsened over much of the West, and there has been little relief for wildfire conditions.

Speaking of those hurricanes, they brought the number of named storms making landfall in the contiguous US to nine for the year. That tied 1916 for the most on record, but Hurricane Delta’s landfall in Louisiana has since added to 2020’s dizzying tally.

September also saw the number of billion-dollar-plus disasters in the US climb to 16—tying 2011 and 2017 for the most in a year since the start of this (inflation-adjusted) metric in 1980.

-

Some of the notable events in December.

-

Each of these disasters caused at least a billion dollars in damages.

-

September wasn’t as warm for the eastern half of the US.

-

Total precipitation was nearly average, but the regional differences are huge.

-

Over 40% of the contiguous US is now in drought.

What next?

NOAA released its winter outlook on Thursday. These long-range outlooks are based on a combination of observed trends, important slow-changing patterns, and model simulations. NOAA typically discusses the next-month and next-three-months outlook, but this round includes the December-January-February seasonal window.

If you caught last month’s update, this will look pretty familiar. The biggest factor in play is the La Niña conditions in the Pacific Ocean, which are likely to persist at least until spring. La Niñas tend to have a pretty defined impact on US winter weather, though the variability of weather doesn’t disappear. But the cold surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific generally promote a shift in the US storm track that leads to more cold and wet weather across the northern tier of the country, with warmer and drier weather across the south.

The outlooks reflect that pattern. For November, above-average temperatures are favored across most of the US, save interior Alaska and a stretch from the Pacific Northwest to the Northern Plains. For the winter months of December through February, odds of average or below-average temperatures expand in those regions.

The precipitation outlook highlights generally shows below-average precipitation favored across the southern half of the country. Odds of above-average precipitation start in the Pacific Northwest (and northwest Alaska) in November and stretch all the way to the Great Lakes region for the winter.

-

November temperature outlook. (Warm colors show probability favoring above-average. EC/white means equal chances of above or below.)

-

Some areas tilt cooler in the December-February timeframe.

-

Here’s the November precipitation outlook.

-

In the winter months, things change a bit.

-

Here’s the expectation for drought conditions over the next three months.

-

Precipitation outlook for October to December.

-

Similarly, here’s the Canadian temperature outlook (October-December).

-

And here’s November-January.

-

The precipitation outlook is a little spottier in November to January.

The implication for the drought outlook is obvious. Drought is likely to expand through Southern California and across the High Plains states. It could also develop in Georgia and North Florida, although recent rainfall in that region provides some buffer. Drought should improve in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and the far Northeast, though, as the La Niña pattern sends water.

Connecting the dots northward, the winter outlook from Environment and Climate Change Canada is a bit more uniform. Above-average temperatures start out favored across Canada, with cooler temperatures creeping in from the west toward January. The precipitation outlook is mostly average, but in the nearer term, the odds favor wetter weather on the western coast and drier weather in the far southeast.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1715208