When did spaceflight begin? There is no single answer.

For newcomers to space, the beginning of time can be traced to as recently as December 2015. That’s when SpaceX landed its Falcon 9 rocket successfully for the first time, opening the modern era of rapid, reusable spaceflight. Increasingly, anything that came before feels anachronistic.

But for those with a bit more perspective, the dawn of spaceflight can be pushed back further back into time, to the 1957 launch of the Soviet Sputnik satellite that shocked the world. This small orbiting spacecraft kicked off the frenetic space race that culminated with NASA’s Apollo 11 Moon landing just a dozen years later.

Yet in a new book, From the Earth to Mars, space entrepreneur Jeffrey Manber takes us back much further into the murk of history to divine the origins of spaceflight. His story goes back a century and a half, telling the tales of some figures who are fairly well known, such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Hermann Oberth, and others a bit less so, including Thea von Harbou and Robert Esnault-Pelterie.

It is difficult to characterize Manber’s book. It’s part graphic novel, with illustrations by Shraya Rajbhandary and cartoon strips by Jay Mazhar, and part essay on the colorful origins and personalities who first conceived of modern rocketry and early attempts to commercialize it. One criticism I have is that the book is only lightly edited and could use some tightening. On the other hand, the colloquial prose is friendly and familiar. More than anything, reading From the Earth to Mars is a lot like having a conversation with Manber. And that’s a delight because he is knowledgeable, warm, witty, and entertaining on these subjects.

Woman in the Moon

There are several main themes in the book, which essentially covers the second half of the 1800s and the first few decades of the 1900s. One is the near total absence—but for some furtive experiments by Robert Goddard—of the United States of America. Space mania in its early decades was most common in Europe and Russia. Another is the lack of intervention by governments. Rather, early space activities were undertaken for commercial or entertainment purposes.

One of my favorite sequences in the book involves German screenwriter and actress Thea von Harbou, who collaborated with her husband, film director Fritz Lang, on the production of the classic film Metropolis. In 1929, she authored a book titled Woman in the Moon, which Lang pitched to studio owners as a potential movie. Von Harbou had been partly inspired to write Woman in the Moon after reading the works of Hermann Oberth and Willy Ley, both of whom had written popular spaceflight books.

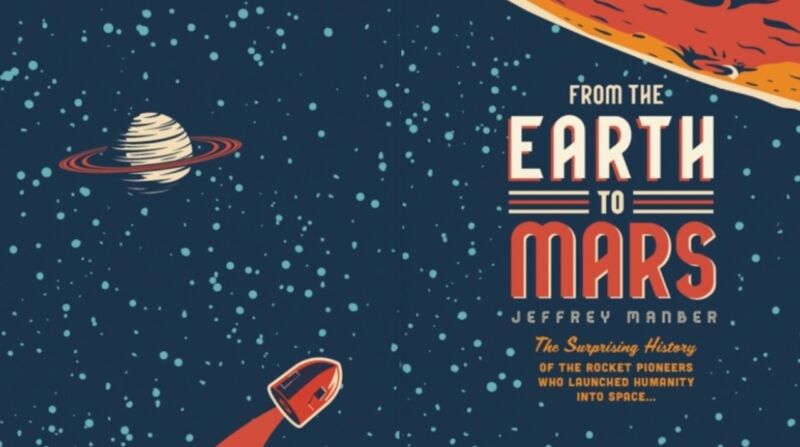

To add to the spectacle of the movie, in which a scientist flies to the Moon to claim deposits of gold in its interior, Lang wanted to film an actual rocket launch. Alas, he only gave Oberth four months to develop the rocket, and predictably, a rocket was not forthcoming in such a short period of time. But Oberth ensured that what was shown on the screen reflected reality to at least some extent.

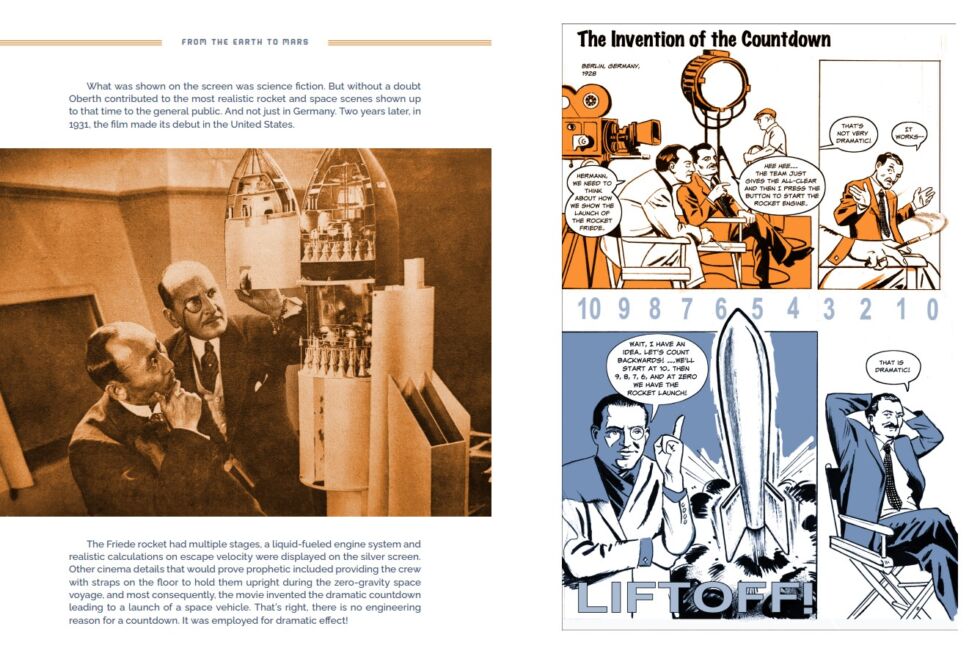

“The Friede rocket had multiple stages, a liquid-fueled engine system and realistic calculations on escape velocity were displayed on the screen,” Manber writes. “Other cinema details that would prove prophetic included providing the crew with straps on the floor to hold them upright during the zero-gravity space voyage, and most consequently, the movie invented the dramatic countdown leading to a launch of a space vehicle. That’s right, there is no engineering reason for a countdown. It was employed for dramatic effect!”

Governments take over

There are a lot of moments like this in the book, where we can see the seeds of modern spaceflight being planted a century ago.

This is history with enthusiasm and attitude. For example, Manber argues that governments sidetracked what was a very happily developing commercial space industry in the 1930s. This happened, of course, because the German government—and others—realized that suborbital rockets would make for good weapons to be dropped on foreign adversaries.

This launched the beginning of V-2 rocket development in the 1930s and ultimately led to the bombing of Britain during World War II, the development of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, and ultimately Sputnik and the space race of the 1960s. It’s interesting to ponder what course history might have taken had wartime needs not interceded with the private space mania nearly a century ago.

Manber’s book is subtitled “Before the Governments were Involved.” The second book in the series, he says, will tackle Russian rocket builders. I look forward to it.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1959045