Early in 2020, I wrote about my experiences of moving to online learning: learning to use new tools, changing the way I taught, and dealing with the challenges of remote assessment. Sitting, unmentioned in the background, was the fact that the faculty where I teach had already agreed to revamp our electrical engineering curriculum, which directs the lives of students during three of their four years here. This raised a rather critical question: do we stick with the old in these trying times, or forge ahead with something new? In the end, we decided that we would press on with the new.

Then, just to add to the confusion, management decided that we should have two student intakes: one in August/September (the traditional starting time for new students), and one in February. This meant that, if we were fast enough, we could trial the new curriculum on a small group of students that started in February, rather than jumping in the deep end in September. After a lot of work, and with much material still to be developed, we think we are ready to roll.

One of the best parts of developing the new curriculum has been the criticism and feedback we’ve had from colleagues, students, and alumni. Now, with a month to go before we’ll be using the new curriculum, I want to open it up to critique by you, the Ars readers. I’m ready to be the Christmas roast.

Out with the old

Our old curriculum is very traditional. We slog through courses of traditional lectures, backed up by practical exercises that, hopefully, link the theory to practice. The students do project work throughout their degree. These projects are a bit like an overgrown vestigial organ: they take a lot of work, but, as far as the students are concerned, don’t have a lot of functionality.

Our assessment is also very traditional. Almost every subject has a written exam. The final grade is entirely determined by the exam, as long as the student has also obtained a passing grade on their practical exercises.

We consistently score low in student satisfaction, and we have a higher than average drop-out rate in first year. Students often fail to see the relevance of what is taught. Furthermore, our students often fail to perceive the links between the different subjects. While the students aren’t overjoyed, employers that take our graduates are happy, observing that they seem to have the right skill set.

The question for us: how can we improve our delivery, so that we reduce the weaknesses, but still graduate students that have the right skill set?

In with the new

We decided that we would drag our curriculum out of the 19th century and squarely into the 20th (education is conservative, so baby steps). The first change was to scrap all the courses. We no longer offer “analog electronics” or anything along those lines. These have been replaced with a set of “learning outcomes.” A learning outcome is a statement about what a student can do. In order to get their study credits, a student has to demonstrate to our satisfaction that they can do.

To take a specific example, one of our learning outcomes reads “You can design, simulate, create and characterize a DC network of passive components with a specified response.” That is a rather vague statement, but it is backed up by a series of more detailed statements that tell the student exactly what we expect to see. For instance, the student should demonstrate that they can simulate a DC circuit, that they can perform accurate measurements on the circuit, that they can hand-calculate the voltages and currents at any node in the circuit, and more.

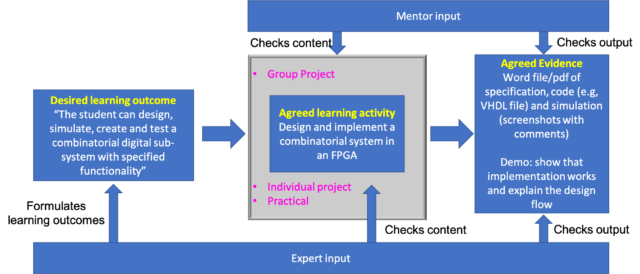

How the student does that is, to a large degree, up to them: they simply have to deliver evidence of their mastery of a learning outcome. To help the students, we provide them with group projects that are defined only in terms of a theme (e.g., healthcare). The student group gets to determine the details of the project. The students take on the portion of the project that’s linked to their learning outcomes. In other words, a student that wants to pursue analog electronics can work on whatever analog electronics are needed to complete the healthcare project. They will use their contribution to the project as evidence of an analog electronics learning outcome. The process is illustrated below.

Maintaining standards, preserving freedom

This gives students a lot of freedom, but that has to be balanced against educational requirements. We have to be sure that the students reach a minimum standard. To ensure that we do this, the students have to describe what they are going to do in their project, and this description has to be signed off by their project mentor and a subject-matter expert. So, if a student wants to obtain their analog electronics learning outcome, they have to propose something that meets the standard set by an analog electronics expert. This is all compiled into a (digital) learning agreement that is signed by all parties.

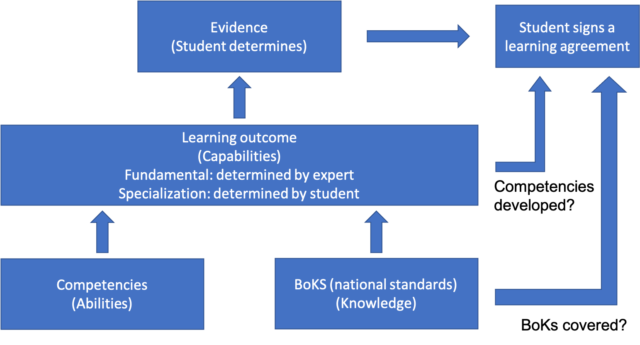

One challenge is that students who are obsessed with one aspect of electrical engineering may neglect other areas. The result would be one-dimensional students who are entirely ignorant of some of the basics in other areas. To avoid this, we have designated certain learning outcomes as mandatory and every student has to achieve those. In that way, we cover the fundamentals of electrical engineering.

Even with the mandatory component, however, we still have nearly half the credits available for electives. Elective learning outcomes are blank. The students are expected to write their own learning outcome, along with describing the evidence that will demonstrate their mastery of the learning outcome. That means that students can take traditional courses at other institutes, or even use their work at a company as part of their education.

The boundary condition is that we (the teachers) have to agree. The student’s learning outcome has to be approved by their mentor and a subject-matter expert. The approval process ensures that the student still has sufficient breadth of knowledge when they graduate. The whole process is illustrated below.

This gives the students the chance to engage with areas that really interest them, hopefully increasing their satisfaction. It also encourages them to consider their education in terms of life after university. They need to justify their choices to themselves and their mentors.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1731628