With Labor Day out of the way, school is afoot here for most high school and college kids in the States—and that, of course, means procrastination by way of gaming. Ars Technica’s staff knows a thing or two about putting off important work by using video or board games as an excuse (let alone the times we make work out of our favorite games), so we used the latest school year as an excuse to recall our favorite risking-our-GPA memories.

Our staff runs a pretty wide gamut of ages and gaming proclivities, so this list includes a nice variety, but it’s incomplete without your contributions. Enjoy our stories for inspiration, then take to the comments and let us know how you juggled your favorite gaming addictions between classes.

My job ate my homework

I managed to turn video gaming into a job at a young age, as I wrote for a daily newspaper’s gaming column through much of my high school and college career. The game that got closest to wrecking my high school GPA was Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, which arrived at my home a few weeks before its retail launch. A tight review-draft deadline for the holiday’s biggest game left me scrambling to juggle entry-level calculus, a high school newspaper editorship, and a proper rumination on Link’s open-world, time-travel journey from boyhood to manhood. (Way to drop a classic before a bunch of pre-Thanksgiving tests and papers, Miyamoto-san.)

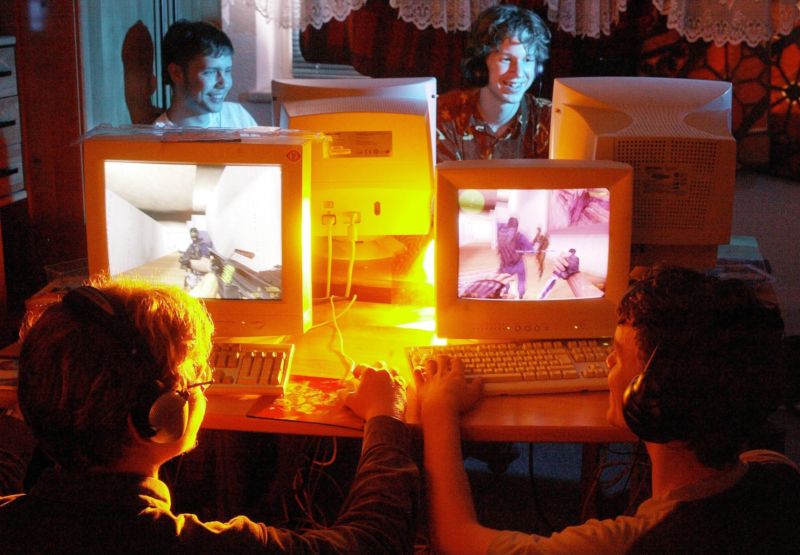

I arrived at the University of Texas in 1999, just in time for every on-campus dorm to be slathered in T1 connections. My random-lottery dorm assignment didn’t just turn out to be the only all-guys dorm on campus; it was also notorious for being full of nerds who lugged giant gaming PCs and CRT monitors to their dorm rooms. I showed up to this dorm with a serious Quake III Arena online-deathmatch addiction, and I was giddy to finally stop getting called out as an “HPB” thanks to my reduced ping. (Look it up.)

The rest of the dorm fell hard for a brand-new Half-Life mod called Counter-Strike, whose networked-multiplayer action left me a bit unsatisfied. (CS 1.6 is a tension-filled classic, obviously, but I’m a rocket-jumping madman at heart.) Instead of switching to a new PC shooter, I leaned into a newfound Dreamcast addiction, since I was my newspaper column’s lead Sega critic at the time. (Tomorrow will mark the Dreamcast’s 20th anniversary in the United States, since it famously launched on 9-9-99.)

Singling out one classic Dreamcast game as a grades-threatening timesink would be disingenuous, but Resident Evil: Code Veronica‘s gorgeous terror was an attention-stealing highlight, while my dorm room became an eventual four-player hub for non-stop doubles Virtua Tennis among friends. That is, when we weren’t all screaming along to Offspring and Bad Religion songs while trading turns in Crazy Taxi.

As a side note, my best gaming friend in the dorm ran a Quake-related fansite in his off hours. I don’t remember its domain, but it was typical of fansites at the time: a massive list of links to other sites’ news and opinion posts, along with my friend’s occasional whiny op-eds. He rigged the site so that pop-up ads appeared in hard-to-spot frames in readers’ web browsers, and he often bragged about the resulting cashflow while showing off his latest PlayStation game purchases or ordering pizzas for anybody who wanted to hang out.

I remember the day the pizzas stopped coming. “My advertising network sent an audit earlier today,” he said with the kind of pained expression I haven’t since seen in my adult life.

—Sam Machkovech, Tech Culture Editor

Dorm shareware chaos before Counter-Strike

Gamers “of a certain age” may remember the 1995 shareware shooter Rise of the Triad. In it, players ran around… shooting things… while bouncing on trampolines. The goal probably involved saving the world, but I wouldn’t know anything about that, because I never ponied up any cash for the rest of the game.

Still, RoTT holds a special place in my heart. It was the first multiplayer game I played against someone not sitting next to me on the couch. RoTT let you dial up another player by modem and, after listening to the soothing static of the two modems shaking hands, some extremely violent gameplay would begin. I used to round up a group of players who took turns playing on my computer, and we took on another team three doors down our college dorm hallway. The real shock was seeing just how another human moved in the game; it was nothing like the computer-controlled enemies, and the difficultly made every kill that much more satisfying.

RoTT was all about the kills, too, offering crazy weapons like the weaving “drunk missile” launcher. Score a particularly amazing hit and your opponent would explode into bloody bits while “Ludicrous gibs!” flashed on the screen. (This was usually followed by the sound of angry shouting drifting down the hall.)

According to Wikipedia, the game was later open sourced and ported “to AmigaOS, Linux, Mac OS, Xbox, Dreamcast, PlayStation Portable and Nintendo DS (homebrew) and 32-bit versions of Microsoft Windows.” I knew nothing of this because, as the group in our dorm moved on to other titles, so did I. But I still have fond memories of those evenings when I should have been studying, letting drunk missiles fly as I bonded with friends around the glow of a CRT monitor and those cries of disappointment down the hall.

—Nate Anderson, Deputy Editor

The “A” in this AD&D stood for “Automation”

When I was in college (1982-1986), “gaming” was still very much a tabletop thing. And one of my friends blamed our regular games of Risk for him not landing an engineering job before graduation. But my primary time-suck was that I was running our group’s Advanced Dungeons & Dragons campaign—and building the tool that would save me more time doing so.

In high school, I had written some fairly complex programs in Apple Basic, including a database program for the Apple II for my dad (who was my high school principal) to track student parking permits. I wasn’t far into my sophomore year at the University of Wisconsin when I realized I could remove a big chunk out of the workload of running AD&D games if I had the paperwork all computerized. So I wrote a menu-driven Dungeon Master’s Familiar, complete with a random-access database for player and non-player character data, random and planned monster encounters, random dungeon generation, and combat resolution—including a manual override for dice throws that the players insisted be physical.

The whole thing ran on an Apple II+ with 64 kilobytes of RAM and dual floppy drives.

—Sean Gallagher, IT Editor

GPA was not one of the eight virtues

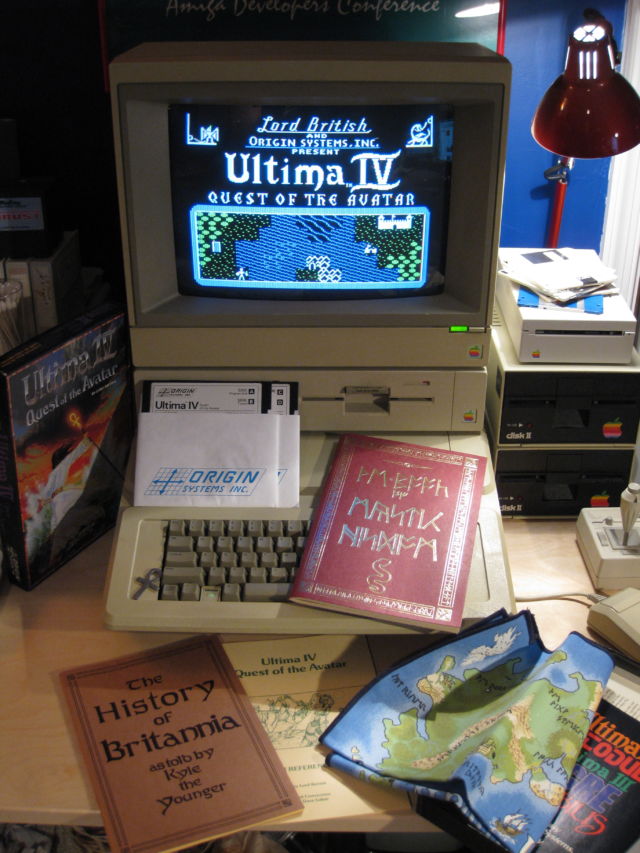

The GPA buster for me wasn’t really in college, it was high school—and the game in question was Ultima IV, played on my Apple IIc.

Ultima IV, aka Quest of the Avatar, was in some ways a radical departure for late 1980s gaming. The focus of the game was supposedly not on beating down monsters but on perfecting the Virtues of the player character themselves: Honesty, Compassion, Valor, Justice, Sacrifice, Honor, Spirituality, and Humility. This frequently required the player to balance decisions on a knife’s edge: do I increase my Valor by defeating these (non-evil but aggressive) enemies at the cost of Justice or my Sacrifice by retreating from battle with them at the cost of Valor?

It was an interesting idea, but at age 17, all I really cared about was treating Britannia as an open, make-your-own-fun sandbox. I wanted to sail the seas, walk the forests, and find all the hidden cities, towns, and dungeons—the heck with the main quest. I generally only worried about the Virtues if one of them being too low kept me out of a new location. I had no real interest in actually becoming the Avatar at all.

Unfortunately for me, Lord British had other ideas. One day, I emerged from a dungeon to discover the entire world map covered in monsters on every single tile. I could magic myself to the nearest town—but upon exiting the town, it was just wall-to-wall monsters again. There was never an actual “game over” message, but it was obvious that Lord British had finally had enough of my BS.

Aside from the wonder of exploring such a huge game space—eight cities, eight towns/castles, eight dungeons, and seven Shrines—Ultima IV offered a young gamer something modern games don’t: unencrypted save files. The joys of using a byte zap utility to cautiously edit the saved file, slowly figuring out which hex codes represented inventory items, equipped items, or character attributes drew me as much as the game itself did. Why should Geoffrey the fighter be the only one to get the good plate mail or Mariah the mage be the only one who can equip the powerful magic wand?

Homework never stood a chance against Ultima IV. I barely squeaked out of high school with a diploma, but the foundational skills I learned forcing Geoffrey the fighter to equip a magic wand—and forcing poor Dupre the paladin to suffer being renamed “Blastmaster”—went a long way in my eventual IT career.

—Jim Salter, Technology Reporter

“Doing lines” in college

One of the four colleges I went to was a small conservatory in the Northeast, and you could play Tetris in the basement computer lab. Even though the game was nearly 15 years old by then, we still wasted enough time playing that we joked in the cafeteria about “doing lines.” One time, a guy got so depressed that he started playing Tetris for hours a day. I’ll never forget the look on his face when his girlfriend quietly begged him, in front of the whole lab, to go to class, and he ignored her. His expression was the platonic idea of self-loathing. I wonder what happened to that dude. I think he played bassoon.

—Peter Opaskar, Line Editor

A LAN party reward for good behavior

When I started college in 1998, networked gaming was still a new and obscure phenomenon. Most people only had dial-up modems if they had Internet connections at all. So the possibilities of gaming on a college LAN were a revelation.

My game of choice was Starcraft, which had only come out a few months earlier. On Friday nights, when many of my peers were out trying to get drunk and/or laid, I’d head down to the computer lab in the basement of the computer science building. The lab was officially closed, but we had friends in the IT department who would give us access to the lab after hours if we behaved ourselves.

PC gaming is more fun when you can do it at the scale of a campus computer lab. Having everyone in the same room allows people to shout encouragement at teammates and taunt opponents.

Starcraft only accommodates eight players per game, so there were sometimes three or four games happening at once. Everyone would start at the same time, then as some games wrapped up (or players were eliminated), stragglers would hover behind those still playing, cheering them on.

Sadly, these semi-organized Starcraft tournaments only happened about once a week. The rest of the time, I’d play smaller-scale games with friends in the dorms. Later we moved into a group house, and I set up a house-wide LAN with ethernet cables snaking along the walls (wi-fi was new, and most desktop computers didn’t have it). This experience was a little different because we’d each go to our separate rooms—on multiple floors—during the game, then afterwards we’d congregate in the hallway to talk through the game and relive our greatest moments.

I didn’t realize what a unique experience this would prove to be. I still play occasional Starcraft games—now Starcraft II—with friends. But my Starcraft-playing friends are now spread out across the country, so we have to play over the Internet. Our days of in-real-life encouragement and trash talk are over.

—Timothy B. Lee, Senior Tech Policy Reporter

The quest that sank the most time

In my college days, I played a lot of games. I’ve always been a fan of MMOs, and World of Warcraft came out while I was in college, so that was dangerous enough. Before the expansions, WoW was extremely demanding of players’ time, even for college students. However, I was pretty casual in WoW compared to some earlier MMOs I played in high school, like Meridian 59 or Ultima Online.

Beyond WoW, I mainly associate gaming in college with three other specific experiences: one was playing split-screen Halo with my friends after class almost every day on the Xbox. I have such fond memories of that game and still enjoy the franchise today. The next was playing LAN party Civilization IV games with my best friend Eryn. We must have played 100 hours together, each on a Dell laptop and sitting in two matching recliners in his living room, Joey-and-Chandler from Friends style—usually with Battlestar Galactica or Star Trek episodes playing on the TV.

But if we’re talking about risking your GPA with games, for me the real danger was Final Fantasy XII, which I played in my last year of college. I stood in line overnight to buy that game, and I’m not going to lie—my grades suffered as I spent my last semester 100 percenting it. To this day, it’s still my favorite Final Fantasy entry. But its length and addictive nature made that one of the most precarious gaming experiences I’ve had in terms of impact on other, admittedly more important things!

—Samuel Axon, Senior Reviews Editor

A different kind of massively multiplayer experience

The reasons for my crappy college GPA were completely unrelated to gaming.

—Eric Bangeman, Managing Editor

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1564019