California’s attorney general—as well as attorneys from three of the state’s largest cities—have sued Uber and Lyft, accusing the companies of violating the labor rights of thousands of drivers. The plaintiffs argue that state law requires Uber and Lyft to treat their drivers as employees, which would make them eligible for minimum wage protections, overtime pay, expense reimbursements, and other benefits they don’t currently receive.

The legal status of ride-hail drivers has been a controversial issue for years. We’ve written about several legal cases over proper driver classification. But so far, those lawsuits have been filed by individual drivers. Uber and Lyft have effectively neutered many of the lawsuits by forcing them into arbitration, denying them class-action status in the process. These lawsuits by individual drivers simply weren’t big enough to make a real impact on Uber and Lyft’s overall business.

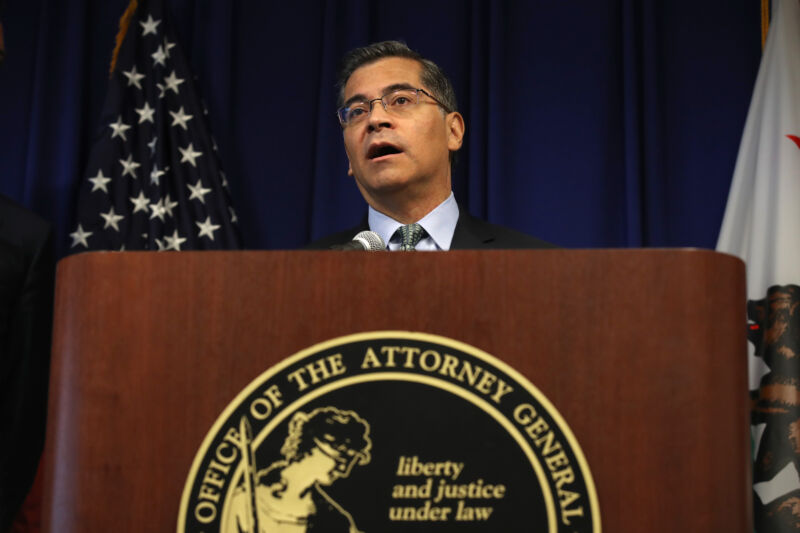

A lawsuit from the state of California is a totally different scenario. Attorney General Xavier Becerra and the city attorneys of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego have enough combined legal resources for a fair fight against the ride-hailing giants. And if Uber and Lyft lose, they could not only owe hundreds of millions of dollars in back wages and other costs, they could also be forced to fundamentally rethink how they do business in the most populous US state.

“Californians who drive for Uber and Lyft lack basic worker protections—from paid sick leave to the right to overtime pay,” Becerra said in a Tuesday statement. “California has ground rules with rights and protections for workers and their employers. We intend to make sure that Uber and Lyft play by the rules.”

But Uber says it plans to fight the lawsuit. “At a time when California’s economy is in crisis with 4 million people out of work, we need to make it easier, not harder, for people to quickly start earning,” Uber said in an emailed statement. Uber says it plans to “raise the standard of independent work for drivers in California, including with guaranteed minimum earnings and new benefits.”

Uber says it sells a technology platform, not rides

Last year, California’s legislature passed landmark legislation that sets a high bar for companies to classify workers as independent contractors rather than employees. Under the so-called “ABC test,” an employer wanting to exclude a worker from employee status must show that the worker meets three criteria:

(A) The person is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work…(B) The person performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business.(C) The person is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business.

To win, Uber and Lyft must prevail on all three of these questions. The companies must show that they don’t control the drivers and that drivers’ work isn’t core to their business and that drivers are engaged in an independent trade.

Becerra and the city attorneys argue that Uber and Lyft drivers don’t meet any of these criteria to be independent contractors. He points out that Uber and Lyft exercise extensive control over the ways their drivers provide services, including deciding which customers a driver should pick up, how much to charge, and where to go. Drivers are given just 15 seconds to decide whether to accept a job and are penalized if they turn down more than a small fraction of rides offered to them, Becerra says in his lawsuit.

Uber has recently made some changes to its app in an apparent bid to preempt some of these arguments. A new version of the app released earlier this year gave drivers more information about riders and allowed them to decline rides without penalty. Uber has also experimented with a new system where drivers set their own fares, with the app matching riders to drivers that make the best offer. It’s not clear how widely these feature are available, however.

On the second prong of the law, Becerra argues that Uber and Lyft’s entire business revolves around selling rides to the public, making drivers obviously core to Uber and Lyft’s “usual course of business.”

But we can expect Uber and Lyft to dispute that. Uber has argued that it isn’t in the business of providing rides to passengers. Rather, Uber says it runs a technology platform that connects drivers with riders.

But the plaintiffs scoff at this as mere hair-splitting. They note that Uber and Lyft don’t allow drivers to decide which passengers to pick or haggle over the fares they charge. When a rider books a Lyft ride, Lyft assigns her a driver, sets the fare, charges the customer’s credit card, takes its cut, and passes the rest on to the driver. In other words, in Becerra’s view, customers are really doing business with Uber and Lyft, not with individual drivers operating independently.

The lawsuit could mean new benefits for drivers but possibly less work

If Uber and Lyft lose the case, it could force dramatic changes in the way the companies do business. Drivers would be entitled to earn a minimum wage, which would probably force Uber and Lyft to restrict how many drivers can log on during periods of low demand—a step they were forced to take in New York after a minimum wage was instituted there. Uber and Lyft would likely also limit the number of hours drivers work each day and week to avoid triggering overtime pay requirements.

Drivers could be entitled to compensation for gas, depreciation, and other expenses for each mile they drive. They could start to earn sick leave, unemployment benefits, paid lunch breaks, and other benefits.

Not only that, but existing drivers could be entitled to back pay, retroactive reimbursements for past expenses, and compensation for missed lunch breaks and other benefits. The lawsuit covers Uber’s practices over the last four years, so some drivers could receive substantial payments.

That would all be great for drivers that get these benefits. But the downside would likely be significantly higher fares—and quite possibly a reduction in business. Data showed that the number of Uber rides fell by 8 percent after the company raised fares in New York in early 2019 when the new minimum wage went into effect. Lyft rides volumes stayed flat during the same period.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1673581