As the US approached the start of the school year in 2020, the guidance it received from the federal government was a mess. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued a series of documents in late July that was a mix of evidence-based risk analysis and full-throated endorsement of having children back in school, with no consideration of risk at all.

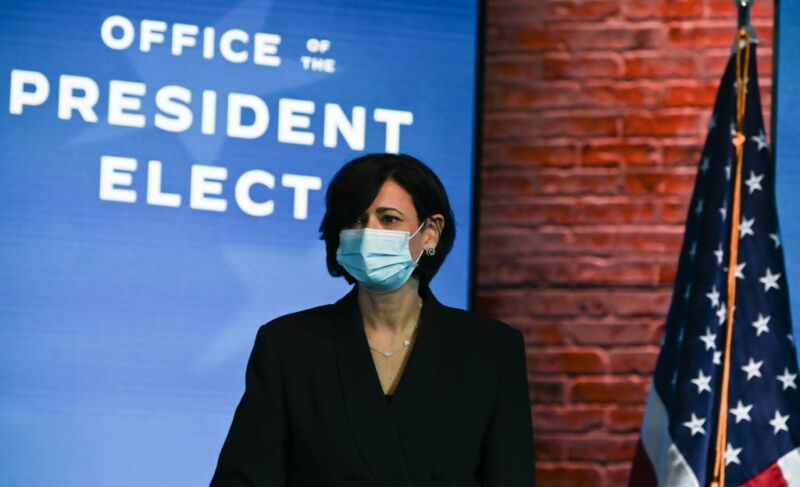

Now, with a new administration in charge and promoting evidence-based policymaking, the CDC has revisited its advice on pandemic safety in schools. The result is a set of documents that are far more coherent in their approach to managing risk. Several documents all promote a single approach to keeping schools open, focused on mask use and distancing, and back that up with an analysis of the latest research on the pandemic’s spread in children. And, in introducing them, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky announced, “I can assure you this is free from political meddling.”

Science-focused

In a press conference announcing the release of the new documents, the count of Walensky’s use of the term “science based” probably reached double digits. Backing that up is one of the three documents released by the CDC on Friday, which focuses entirely on the evidence that was used to formulate the new guidelines. The document makes clear that a lot of the information we now have has come from analyses of what happened after schools were reopened in the autumn, both in the US and overseas. This makes it clear that, even if it weren’t for the change in administration, we were due to revisit our thinking about school safety.

One thing that has remained consistent is that school-age children seem to be less severely affected by COVID-19 than adults. As the US approaches half a million people killed by the pandemic, only 203 of the victims have been under the age of 18. Symptoms in general appear to be less severe in younger individuals, and there are some indications that children are more likely to have asymptomatic cases.

That has ensured that children are less likely to be tested, which has made it harder to determine the spread of the virus between children and from children to adults. The CDC notes that there are some indications that spread via children may be less frequent, but the evidence here is much less certain.

The lower incidence of spread among children would tend to indicate that the risk to children in schools is lower. But the CDC also notes that, in cases where safety guidelines aren’t followed, there have been instances where schools have allowed significant spread of SARS-CoV-2. But safety guidelines can make a big difference. “When mitigation strategies—especially mask use and physical distancing—are consistently and correctly used,” the CDC document states, “the risk of transmission in the school environment is decreased.”

The other key piece of data that informs the new guidelines is on the relationship between spread in the community and that in schools. The CDC says that, for every five additional cases per 100,000 in the community, the risk of an outbreak in schools goes up by over 70 percent.

Science into policy

So, how do you convert that information into policy? In the CDC’s case, there are two key features. One is what Walensky called “layered mitigation.” She said that individual policies each provide a degree of protection, and layering each protection on top of the others can do far more than any individual one can on its own. The five layers the CDC is calling for are:

- Mask use. Mandatory under all circumstances, with guidance on how to wear them effectively.

- Distancing. Beyond spacing students in schools, use small class groups that stay together all day, stagger schedules, etc.

- Handwashing and respiratory etiquette. Make sure students know how to keep themselves and others safe.

- Healthy facilities. Improved ventilation, regular disinfection.

- Contact tracing and isolation. Handled in coordination with local health authorities.

The first two of these—mask use and distancing—are considered the most essential components of the strategy and the ones with the clearest evidence of their effectiveness. But all five are considered central to any strategy to reopen schools safely.

As the Biden administration is expected to boost national testing and vaccination plans, the CDC recognizes that both can also play a role in school safety. While vaccine safety in children is only starting to be tested, vaccination of teachers and staff can help improve safety. And regular screening, if available, can identify and isolate people at risk of spreading the virus in schools and, so, limit the pandemic’s spread. But the guidelines appear to be written with the sense that testing and vaccines are a welcome addition, rather than something that can be relied upon in the immediate future.

Community matters

In addition to describing these policies, the CDC also provides some advice on when they’re most needed. As mentioned above, the spread of the virus in the community has a profound effect on the risks posed within schools. These are defined in terms of both the number of positive tests per capita, as well as the frequency of tests that return positive results (called positivity, this acts as a measure of testing capacity).

A low rate of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is defined as fewer than 10 cases per 100,000 people within the last week, with less than 5 percent of tests returning a positive result. Those numbers shift gradually to high transmission, which is defined as over 100 cases per 100,000 people, and a positive test rate of over 10 percent.

At low and moderate transmission, the CDC advises that schools can be open for full in-person education, with some tolerance for lapses in our ability to keep everyone distanced at all times of the day. This includes allowing sports and other extracurricular activities, although these should be curtailed as the risk of transmission shifts to moderate.

When transmission reaches levels termed substantial, extracurricular activities are eliminated unless they can be held outdoors and with distancing. Physical distancing inside schools becomes mandatory at all times, and teaching shifts to hybrid modes with reduced in-person attendance. At high transmission, students over the age of about 12 shift to remote education, since their risks are thought to be more similar to those of adults. The only exceptions are schools where all of the elements of layered mitigation can be adopted with total compliance. Extracurricular activities are virtual only.

The documents make it clear that evaluating spread in the community is an ongoing activity, and school authorities need to be ready to shut their schools down entirely should conditions indicate this is needed.

In conjunction with these documents, the Department of Education has also issued a document that reiterates much of the CDC’s guidance. In addition, it goes into some of the practicalities on how to create pods of students that are kept together all day and how to bus kids to and from schools while maintaining the distancing advised by the CDC.

A “long needed roadmap”

In introducing these documents, CDC Director Walensky emphasized that “the safest way to open schools is to ensure there is as little circulating disease in the community as possible,” and she went on to call keeping schools open a “shared responsibility.” But right now, we’re nowhere close to handling that responsibility. She said that only 5 percent of counties in the US would currently fall into the low community spread category, while about 90 percent of them would fall into the highest.

Walensky also emphasized that the CDC wasn’t mandating anything via these documents; they were meant to act as “a long needed roadmap” to help guide schools through the process of opening (or keeping open) their schools in a way that’s safe.

Overall, the new documents make a welcome change. While some elements of these documents had been developed during the Trump administration, they were consistently undercut by contradictory messages from different agencies, and political signaling that promoted full school opening regardless of risk.

And that last element may end up undercutting even the best-designed school guidelines. In the US, educational policy decisions happen at the state and local level, and many of these governments are run by people who have gone in for the “open regardless of risk” approach, and the disdain for distancing and mask use that have accompanied it. It will be a difficult fight to get them to adopt the CDC’s guidance.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1742201