-

A sample video shows how computer vision (running on an external computer) detects the enemy and calculates how far the mouse needs to move to target that enemy.

-

Just a few frames later, thanks to inputs sent through external hardware, the cheat user automatically targets the enemy and fires.

-

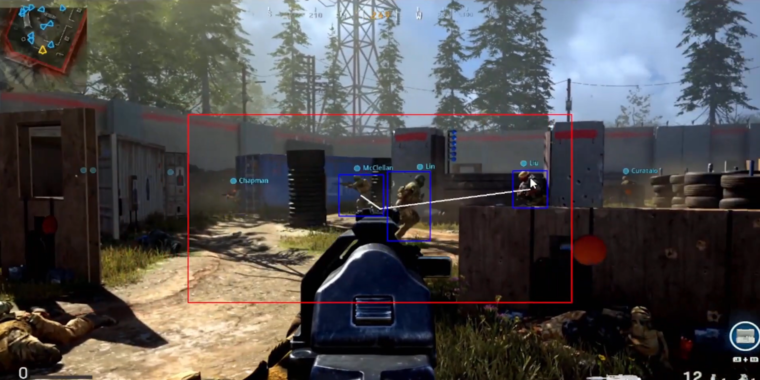

Another demonstration of computer vision identifying multiple valid targets inside the central “kill zone”

-

The detection seems to work quickly in a variety of lighting and obscuring conditions.

-

Input devices like the Titan Two are key to making computer vision cheat tools like this work.

When it comes to the cat-and-mouse game of stopping cheaters in online games, anti-cheat efforts often rely in part on technology that ensures the wider system running the game itself isn’t compromised. On the PC, that can mean so-called “kernel-level drivers” which monitor system memory for modifications that could affect the game’s intended operation. On consoles, that can mean relying on system-level security that prevents unsigned code from being run at all (until and unless the system is effectively hacked, that is).

But there’s a growing category of cheating methods that can now effectively get around these forms of detection in many first-person shooters. By using external tools like capture cards and “emulated input” devices, along with machine learning-powered computer vision software running on a separate computer, these cheating engines totally circumvent the secure environments set up by PC and console game makers. This is forcing the developers behind these games to look to alternate methods to detect and stop these cheaters in their tracks.

How it works

The basic toolchain used for these external emulated-input cheating methods is relatively simple. The first step is using an external video capture card to record a game’s live output and instantly send it to a separate computer. Those display frames are then run through a computer vision-based object detection algorithm like You Only Look Once (YOLO) that has been trained to find human-shaped enemies in the image (or at least in a small central portion of the image near the targeting reticle).

Once the enemy is identified on the screen, these cheating engines can easily calculate precisely how far and in which direction the mouse needs to move to put that enemy (or even a specific body part, like the head) in the center of the crosshairs. That data is then sent to an input-passthrough device like the Titan Two or the Cronus Zen, which emulates the correct mouse input and fires a shot at superhuman speed.

On their own, all of these external devices and tools have legitimate uses (though the automated macros enabled by input-passthrough devices are controversial in many competitive gaming circles). Put them all together, however, and you get an effective cheating engine that doesn’t require any modifications to the software or hardware that’s actually running the game. In a way, it’s kind of like printing a gun from basic 3D-printer resin, or building an explosive from chemicals derived from legal products.

“Why create a bomb that can destroy the world?” one cheat maker asked rhetorically in a Discord conversation with Ars Technica. “But we did it.”

The cheat factory

Cheating methods based on external tools and emulated inputs aren’t entirely new. But they have gained increased attention in recent days thanks to a promotional video from the makers of a specific cheat tool we’ll be calling CVCheat (Ars won’t be naming the actual cheat tool here or linking to it in this piece). Many of CVCheat’s promotional videos were taken down from YouTube through an Activision copyright claim sometime in the last 24 hours, but the most recent is mirrored in this tweet, sans any identifying information.

The current versions of CVCheat provides some basic automation features, including a “trigger bot” that detects when an enemy is in the player’s crosshairs and automatically sends a shot command. The current tool also features automatic recoil adjustment that can steady the players’ aim by virtually moving the mouse to reverse the recoil after every shot (optical character recognition helps detect what weapon is being used for specific recoil adjustments in this case).

-

A mock-up of the user interface for one computer vision cheat tool, showing how it can be configured for head, body, or leg shots.

-

Users may need to play with detection threshholds and speed settings to get the cheat tool working correctly, the maker says.

-

The size of the central “kill zone” can be changed, affecting the detection speed and how far the auto-aim “snap” can go.

-

Access to higher “tiers” of the cheat tool is granted to users that make “donations” to the maker.

But it’s the upcoming version of CVCheat that the makers promise will take things to the next level with computer vision based “undetectable, unstoppable full auto-aim [and] full auto-shots” that works on “any game” on PC, Xbox, or PlayStation. The Pro version of CVCheat that promises these benefits is offered in exchange for a $50 “donation” to the makers; while that specific quid pro quo arrangement has disappeared from CVCheat’s website in recent days, it’s still explicit on the makers’ Discord channel.

The admin of the CVCheat Discord (who we’ll be referring to as LordofCV here to obscure the tool’s name) said their tool wasn’t intended to ruin the competitive balance of online shooters. Instead, they say it’s meant “to give console players a chance in [games] that are already overrun with hackers. Xbox players don’t stand a chance… the script would never had been created without request [from users]!”

The upcoming version of CVCheat can detect an on-screen enemy and fire in about 10 ms, according to LordofCV, and works effectively on games running at up to 240 fps. The detection algorithm currently “takes some adjusting” on the part of the user, they explained, but the threshold can be adjusted “to pick up anything that moves.”

Still, the algorithm works best when the target is a large identifiable figure on screen rather than a far off blob of tiny pixels. “Once you lock it on [it] works really good [at] close to mid-range, [and] long-range with a sniper scope it works fine,” LordofCV said.

LordofCV claimed he helped come up with the idea for the CVCheat tool and helps manage the community, while another coder does all the scripting and receives the donations. They say that CVCheat currently has about 200 users.

Detect and evade

Speaking to Ars, LordofCV expressed extreme confidence that their cheating method was completely undetectable, because “we are not manipulating any game files… it’s use at your own risk but cheat detection software can’t pick it up.”

At least one person in charge of actually protecting online games from cheaters took issue with that boast, though. “Ultimately, the ‘emulated input’ vector isn’t anything new, and the Vanguard team is very aware of it,” Valorant Anti-cheat Lead Phillip Koskinas told Ars Technica. “Cheaters are always looking for new corners to hide in, and ‘Kernel Drivers’ have never been the most important tool in our arsenal.”

Koskinas pointed specifically to a 12-month ban Riot issued for former Beşiktaş Esports player Yasin “Nisay” Gök back in February. Without going into too much detail, that ban announcement notes that Nisay was banned after “an automated system built by the [Valorant] Anti-cheat team to aid in cheat detection flagged the account for use of a cheat that reads the user’s screen before emulating corrective mouse movement with the assistance of external hardware.” Human confirmation after that automatic flagging confirmed the cheating, Riot said, suggesting a mix of software tools and human review can indeed detect these “external” cheating methods just fine.

Koskinas didn’t go into detail on Riot’s methodology: “Anti-cheat is partially a game of obscurity,” he said, “so we really wouldn’t want to bring unnecessary visibility to this topic.” But despite their “undetectable” boast, LordofCV hinted that observant players and/or analysis software could still notice the superhuman aim-and-fire speeds that show up when these cheats are used. “Kill cams are gonna be killer… meaning it’s suspect,” they said. “Humans can only do things so fast, [and] this software does it faster.”

Still, LordofCV suggested that it can be hard to differentiate between external emulated inputs and legitimate pro-level human gameplay, at least at a quick glance. “I’ve seen players that are [just] genuinely good at [the] game get banned,” they said. “You can get banned for no reason on most games.”

Whatever the case, it’s clear external computer vision-assisted techniques are going to continue to be an evolving front in the never-ending battle between cheaters and those that want to stop them. As artificial intelligence techniques continue to develop, it may get even easier for these external tools to disguise their use and harder for anti-cheat algorithms to even detect their existence. The cat-and-mouse battle continues.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1779166