Intel and other semiconductor companies have joined together with industrial materials businesses to fight US clampdowns on “forever chemicals,” substances used in myriad products that are slow to break down in the environment.

The lobbying push from chipmakers broadens the opposition to new rules and bans for the chemicals known as PFAS. The substances have been found in the blood of 97 percent of Americans, according to the US government.

More than 30 US states this year are considering legislation to address PFAS, according to Safer States, an environmental advocacy group. Bills in California and Maine passed in 2022 and 2021, respectively.

“I think clean drinking water and for farmers to be able to irrigate their fields is far more important than a microchip,” said Stacy Brenner, a Maine state senator who backed the state’s bipartisan legislation.

In Minnesota, bills would ban by 2025 certain products that contain added PFAS—which is short for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances—in legislation considered to be some of the toughest in the country.

The Semiconductor Industry Association—whose members include Intel, IBM, and Nvidia—has cosigned letters opposing the Minnesota legislation, arguing its measures are overly broad and could prohibit thousands of products, including electronics. Chipmakers also opposed the California and Maine laws.

The pushback in the US echoes a dispute in Europe, where chipmakers have warned that a proposed ban on PFAS will disrupt semiconductor supplies.

Long-term PFAS exposure can weaken the immune system, decrease infant and fetal growth, and increase kidney cancer risk in adults, according to a 2022 report by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

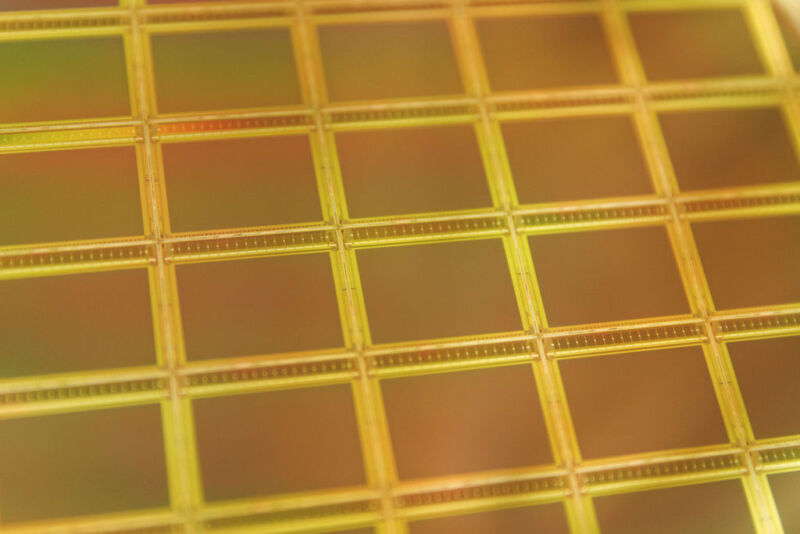

Widely used in products from non-stick cookware to firefighting foam to ski wax, PFAS are also widely used in semiconductor manufacturing. Chip companies have said there are typically no alternatives to PFAS for their manufacturing.

“In the applications I am aware of, there are not viable substitutes available at commercial scale,” said John Rogers, a senior vice-president at Moody’s who covers chemicals makers.

The state measures come as federal regulators also move to control PFAS. Last week the US Environmental Protection Agency proposed to limit the chemicals in drinking water, citing health risks. The proposal, which is open for 60 days of public comment, would lead to new rules that the EPA wants finalized by the end of this year.

If fully implemented, “the rule will prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses,” the EPA said.

Intel added PFAS to the issues it lobbied on starting in 2021, according to federal disclosures. In 2022 the company helped to launch the Sustainable PFAS Action Network, a lobbying group that has opposed the PFAS legislation in California and Minnesota. The executive director of the organization, Kevin Fay, has been an external lobbyist for Intel since at least 2008, regulatory disclosures show. The Sustainable PFAS Action Network is also representing the Semiconductor Industry Association.

Fay said companies are reviewing the EPA’s proposal. Intel declined to comment.

US PFAS regulations do not yet pose a significant risk for semiconductor companies, but if new rules are adopted, costs will probably be passed on to consumers in higher prices, said Jason Pompeii, a senior director at Fitch.

“There will be a tax incurred to remediate, which will hopefully drive innovation and alternatives to PFAS” in semiconductor manufacturing, he said.

© 2023 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1926260