The bodies of our Solar System’s asteroid belt have violent pasts. Some, like the dwarf planet Ceres, have seen their interiors restructured under the force of gravity while having their surfaces blasted by collisions. Smaller asteroids have experienced collisions that completely shattered them, leaving their debris’ weak gravity to pull the pieces together into a rubble pile. Now, new images of the fourth-largest body in the asteroid belt, Hygiea, suggest it has a history that’s somewhere between the two. After suffering a shattering collision in the distant past, the body’s remains had enough gravitational pull to shape it into a dwarf planet.

History vs. observations

We know Hygiea has experienced a collision in the past, because we can see its remains. An entire family of small asteroids are found in orbits that suggest they originated from the asteroid about two billion years ago.

In other cases where we’ve seen asteroid families like this, the body on which they originated is either pockmarked with craters and/or has suffered at least one extremely large collision. So, planetary scientists probably had similar expectations in mind when they turned the Very Large Telescope at the European Southern Observatory toward Hygiea in 2017.

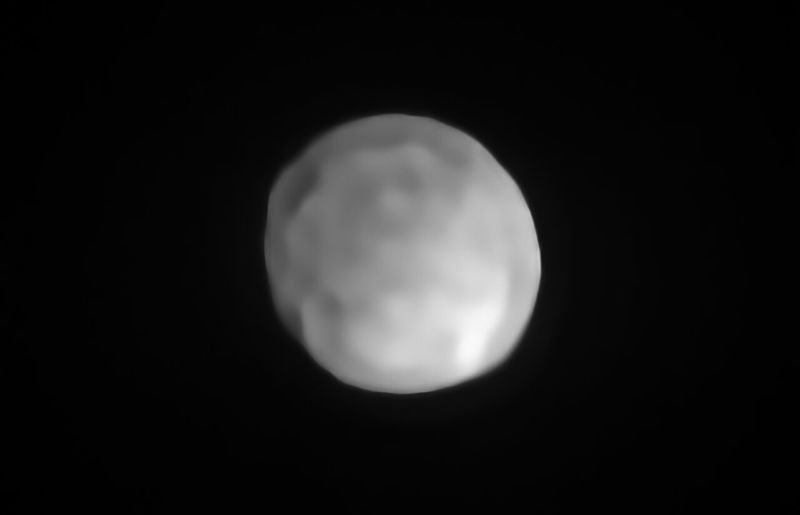

Instead, the body they imaged was remarkably smooth and nearly spherical—its average radius is 217km and likely only varies from 225km to 212km. It was also rotating at roughly twice the rate that we thought it had been.

None of that is quite what was expected: “None of our images and their associated contours revealed the large impact basin expected from the large size of the Hygiea [asteroid] family.”

To figure out how the asteroid family could have formed, the researchers built a model that allowed them to try out different collisions, testing different impactor sizes and angles of impact. After using these collision models to generate debris, the researchers let gravity take over to figure out what the re-formed Hygiea and its remaining debris (which would go on to form the asteroid family) would look like.

Rather than forming a large crater, the collisions that worked instead completely shattered the asteroid. This could be done either by a head-on collision with a 75km object or an off-center collision with a 150km object. The off-center collisions, however, tended not to leave any large bodies in the debris (other than Hygiea itself); since some members of the resulting asteroid family are larger, the researchers conclude that a head-on collision is most likely.

Liquified

In addition to liberating a debris field, the collision turned the remains of Hygiea into a fluid, which underwent large-scale oscillations for about four hours after the event. This allowed the debris to evenly mix and equilibrate, producing the body’s current spherical shape. This was probably enabled by the relatively low density of the material; the researchers estimate that Hygiea is less than twice as dense as water.

This is similar to the density of Ceres, the largest body in the asteroid belt. The authors suggest that the two formed further out than the “snow line” of water, the point where material was far enough from the Sun for water to remain frozen.

The authors also argue that the collision may have incidentally turned Hygiea into a dwarf planet. As they note, anything in the asteroid belt orbits the Sun and isn’t orbiting a larger body, fulfilling two of the four requirements for dwarf planet status. These bodies should also have cleared their orbit; that depends somewhat on the orbits of the other material in the same asteroid family—presumably, if they were close enough, they’d already have been incorporated back into Hygiea.

That leaves one last hurdle: does Hygiea have enough mass to form a spherical shape under the force of its own gravity? It’s not clear what Hygiea looked like before the collision, as some other large asteroids like Eros have pretty irregular shapes. But after its disruption, Hygiea’s gravity was clearly sufficient to shape it into a sphere. As a result, the researchers suggest it should be designated a dwarf planet, the smallest one yet.

Nature Astronomy, 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-019-0915-8 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1593455