For months, members of Conti—among the most ruthless of the dozens of ransomware gangs in existence—gloated about publicly sharing the data they stole from the victims they hacked. Now, members are learning what it’s like to be on the receiving end of a major breach that spills all their dirty laundry—not just once, but repeatedly.

The unfolding series of leaks started on Sunday when @ContiLeaks, a newly created Twitter account, began posting links to logs of internal chat messages that Conti members had sent among themselves.

Two days later, ContiLeaks published a new tranche of messages.

Burn it to the ground

On Wednesday, ContiLeaks was back with more leaked chats. The latest dispatch showed headers with dates from Tuesday and Wednesday, an indication that the unknown leaker continued to have access to the gang’s internal Jabber/XMPP server.

“Hello, how are things with us?” a Conti worker called Tort wrote in a Wednesday message to a gang colleague named Green, according to Google Translate. Tort went on to report that someone had “deleted all the farms with a shredder and cleaned the servers.” Such a move suggested that Conti was dismantling its considerable infrastructure out of fear the leaks would expose members to law enforcement investigators around the world.

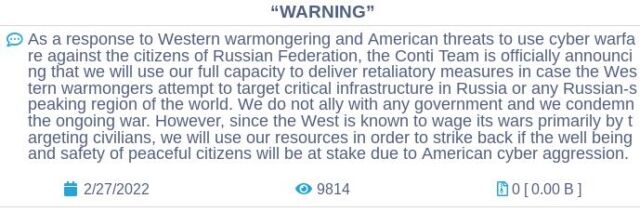

In another tweet, ContiLeaks wrote, “Glory for Ukraine!” This implied that the leak was motivated, at least in part, to respond to a statement posted to Conti’s site on the dark web that group members would “use our full capacity to deliver retaliatory measures in case the Western Warmongers attempt to target critical infrastructure in Russia or any Russian-speaking region of the world.”

KrebsOnSecurity, citing Alex Holden, the Ukrainian-born founder of the Milwaukee-based cyber intelligence firm Hold Security, has reported that the ContiLeaks is a Ukrainian security researcher. “This is his way to stop them in his mind at least,” KrebsOnSecurity adds. Other researchers have speculated that the leaker is a Ukrainian employee or business associate of Conti who broke with Conti’s Russia-based leaders when they pledged support for the Kremlin.

In all, the leaks—which are archived here—chronicle almost two years’ worth of the group’s inner workings. On September 22, 2020, for instance, a Conti leader using the handle Hof revealed that something appeared to be terribly wrong with Trickbot, a for-rent botnet that Conti and other crime groups used to deploy their malware.

“The one who made this garbage did it very well,” Hof wrote while poring over a mysterious implant someone had installed to cause Trickbot-infected machines to disconnect from the command and control server that fed them instructions. “He knew how the bot works, i.e. he probably saw the source code, or reversed it. Plus, he somehow encrypted the config, i.e. he had an encoder and a private key, plus uploaded it all to the admin panel. It’s just some kind of sabotage.”

There will be panic… and groveling

Seventeen days after Hof delivered the analysis, The Washington Post reported that the sabotage was the work of the US Cyber Command, an arm of the Department of Defense headed by the director of the National Security Agency.

As Conti members attempted to rebuild their malware infrastructure in late October, its network of infected systems suddenly mushroomed to include 428 medical facilities in the US, KrebsOnSecurity reported. The leadership decided to use the opportunity to reboot Conti’s operations by deploying its ransomware simultaneously to health care organizations that were buckling under that strain of a global pandemic.

“Fuck the clinics in the USA this week,” a Conti manager with the handle Target wrote on October 26, 2020. “There will be panic. 428 hospitals.”

Other chat logs analyzed by KrebsOnSecurity show Conti workers grumbling about low pay, long hours, grueling work routines, and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

On March 1, 2021, for instance, a low-level Conti employee named Carter reported to superiors that the bitcoin fund used to pay for VPN subscriptions, antivirus product licenses, new servers, and domain registrations was short by $1,240.

Eight months later, Carter was once again groveling.

“Hello, we’re out of bitcoins,” Carter wrote. “Four new servers, three vpn subscriptions, and 22 renewals are out. Two weeks ahead of renewals for $960 in bitcoin 0.017. Please send some bitcoins to this wallet, thanks.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1837820