There aren’t enough game consoles in the world for our upcoming locked-down holiday. Good luck finding a PS5 for Christmas. As Nintendo similarly struggles to keep up with demand, the number of people searching iFixit for Switch repair guides has more than tripled since last year. Traffic to our Joy-Con controller repair page started growing dramatically on March 14—the day after President Trump declared a national emergency. It’s been surging ever since. At a time when so many of us are turning to games for fun, stress relief, and social connection, it is imperative for our collective sanity that we press every game console into service.

But if you talk with expert repair technicians like Bryan Harwell, they’ll tell you that significant obstacles stand in the way.

At Replay’d, Harwell’s Boston repair and game shop, one out of every 10 customers brings in a console with a broken optical drive. Not only does a broken drive mean you can’t play your favorite discs, but on most Xbox and PlayStation models, a faulty DVD or Blu-ray drive will cause the whole console to stop working, even if the owner mostly plays downloaded, digital games. Harwell has hundreds of Xboxes in the shop basement that his technicians could harvest drives from, but there’s a catch—an obscure part of US copyright law makes it illegal for him to repurpose those drives. All too often, he’s had to give a hopeful child a dour prognosis: The only cost-effective way to fix their console is illegal. The only legal path requires parts so expensive that they’d be better off buying a new console (if they can find one).

The root of the problem is that Microsoft and Sony lock down the software they use to pair their disc readers with their consoles’ motherboards. Shops like Replay’d could easily replace those drives by accessing the software pairing the drives with the boards. Instead, the repair industry is cowering in fear of a relatively obscure provision of copyright law banning the removal of digital locks that’s kept everyone from gamers to farmers and hospitals from fixing the devices they own.

Fortunately, Congress built an escape hatch. Every three years, the Librarian of Congress decides that, for certain products, circumvention of these digital locks should be allowed. That time is once again upon us. Next week, with the help of Public Knowledge and our fellow advocates for Right to Repair, iFixit will ask the US Copyright Office to make fixing consoles, along with other software-enabled devices, legal.

Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, passed by Congress in 1998, makes it illegal to “circumvent a technological measure that effectively controls access to a copyrighted work.” In Harwell’s case, the copyrighted work is the firmware on the optical drive.

Manufacturers, and the Copyright Office, have interpreted this to mean that maneuvering around the digital locks on your own devices in order to fix them is against the law. And the penalties for breaking this law are harsh, with fines up to $150,000 and even jail time.

The result is that too many beloved consoles are heading for the trash heap rather than getting regifted under the Christmas tree. That’s a shame, because the demand is there—iFixit’s Xbox and PlayStation repair pages get hundreds of thousands of hits every year.

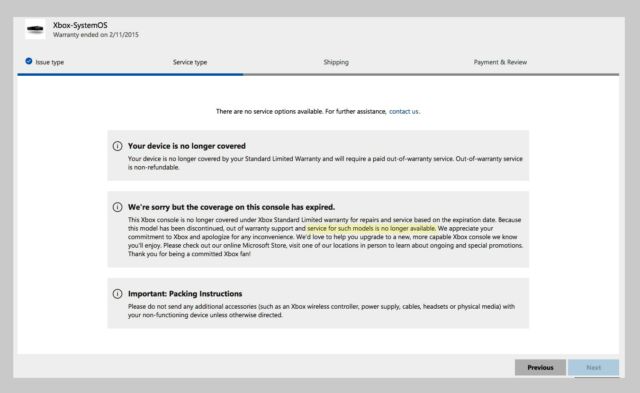

Manufacturers argue that enabling repair will open a Pandora’s box of game piracy and cheating. But pirates and cheaters aren’t deterred by copyright law. The Entertainment Software Association claims that the locks are necessary to “to prevent users from making unauthorized copies.” They point out that manufacturers have mail-in repair programs and will happily fix your console for a fee. But when I logged in to Microsoft.com to see what it would cost to fix the drive in my Xbox One, they told me “there are no service options available.”

If the manufacturers won’t fix them, then consumers and repair shops will have to maintain their consoles themselves. But all the latest consoles have locks getting in the way of standard repairs, and gamers are stuck without options. After modders discovered a way around the Xbox 360’s safeguards with a drill and a resistor, Microsoft built a custom circuit board onto the Xbox One optical drive. That game-verifying board shares a secret key with the main processor, and removing either one causes the system to fail.

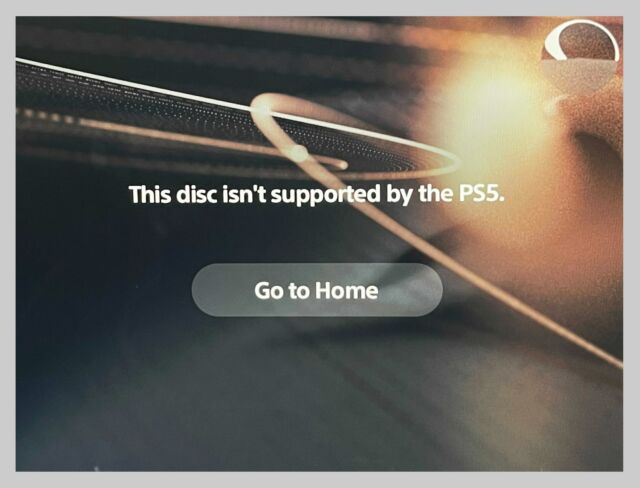

Earlier this month, we took apart the Xbox Series X and the PlayStation 5. Both offer optical drives that let you enjoy your library of older game discs, but after trying to swap the drives between two of our brand-new PS5s (this is only slightly a humblebrag that we have two glorious new consoles), the console complained that our newly unwrapped copy of Spider-Man: Miles Morales “isn’t supported by the PS5.” We quickly swapped them back. Sadly, the new Xbox also pairs its optical drive and motherboard.

That leaves gamers stuck with a catch-22: The manufacturers won’t fix their consoles, and it’s illegal for them to do it themselves. That’s why we go back to Congress every three years seeking exemptions. And it’s worked: We’ve successfully legalized unlocking cell phones, modifying smart home devices and vehicles, and fixing tractors. But three years ago, they denied my request for video game repair—leaving console gamers in the lurch.

Game consoles aren’t the only things that are illegal to fix. Philips is suing companies who repair medical equipment for hospitals, arguing that they have circumvented digital locks in the course of their work. Sound familiar? That’s because there’s not much practical difference between the software in your console, your smartphone, or a ventilator. They’re all just computers. But the Copyright Office insists on defining these categories so narrowly that we have to apply for separate exemptions for each type of product. For instance, the Copyright Office requires us to apply for a different exemption for smart televisions than smart refrigerators, even though Samsung uses the same Tizen operating system for both. Accessing the software in the exact same John Deere engine in a tractor or a boat requires two totally different exemptions. According to the Copyright Office, the former is currently allowed and the latter is not.

Hopefully some boat mechanics will band together to hire expensive IP lawyers that can ask Washington to make their trade legal again. If that sounds ludicrous, that’s exactly what Summit Imaging and Transtate Equipment, two medical servicing companies, are doing right now.

This hodgepodge of product-specific exemptions is the result of a process that is biased against tech users. Having to go to the Copyright Office every three years, hat in hand, to ask for permission to simply fix our stuff is infuriating. Congress thinks so too, and Representative Zoe Lofgren of California has repeatedly introduced legislation that would grant a permanent exemption to Section 1201 for activities like repair that don’t otherwise violate copyright law.

A lot has happened in the last three years, and a lot will happen in the next three. Tech moves at a speed that far outpaces the Copyright Office’s exemption process. There’s no way current copyright exemptions can predict (and protect us from) new repair-hostile practices, emerging tech, or a global supply-chain breakdown. The Copyright Office may believe it’s protecting the content industry’s interests, but in reality, it’s hamstringing essential repair services—critical to keeping the things that power our economy running—with arbitrary rules and burdensome administrative processes. We can’t keep playing exemption whack-a-mole. Consumers deserve the right to repair everything that they own.

Unfortunately for now, we’re stuck with a broken law. But an exemption for gaming consoles will help people and repair shops get consoles working again, save more circuit boards from clogging waste streams, and get you back to playing your favorite games.

Even though manufacturers keep releasing new consoles, repair shops are seeing real demand to keep older game consoles running. Harwell knows there are some customers who—out of nostalgia, frugality, or a desire to appease the kids—want to fire up an earlier Xbox or PlayStation and jam with some old favorites.

But the inability to fix consoles without a new motherboard or time-consuming soldering work make repairs more expensive than they need to be. Tim Mentzer, owner of Mentzer Repairs in Ephrata, Pennsylvania, estimates that locked-down parts are responsible for about 70 percent of decommissioned consoles at his shop—either because of physical impossibility or because the required parts make it too expensive for his customers.

When I spoke to Harwell at Replay’d, he didn’t mince words, “Microsoft and Sony are being irresponsible,” he told me. “It’s irresponsible that they make consoles with a part that could be easily replaced so difficult to [repair]. You could prevent all the waste once the drives go bad. We end up with all these boxes just recycled and trashed.”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1729471