We here at Ars were somewhat surprised to stumble across a BBC headline indicating that a university-industry partnership in Japan was working on developing wooden satellites. The plan is less insane than it sounds—wood is a remarkable material that’s largely unappreciated because of its ubiquity. But most of the reasons to shift to wood given in the coverage of the plan completely misses the mark.

To the degree that there is a plan, at least. According to the BBC and other coverage, the partnership is between Kyoto University and a company called Sumitomo Forestry. But neither the university nor the company has any information on the project available on the English-language versions of their websites. The BBC article gets all its quotes from Takao Doi, who’s currently faculty at Kyoto University. According to Doi, the collaboration is on track to be manufacturing flight models of wooden satellites by 2023.

While wood may seem like a horrific fit for the harsh environment of space, the idea may seem less insane if you think of wood in terms of its structural composition: a mix of two robust polymers, cellulose and lignin. The strength and durability of wood depends heavily on the ratio of these polymers and what’s also present in the mix with them. But it’s also possible to physically and chemically treat wood to alter its properties further. One version of wood was as strong as aluminum by some measures, and had some interesting additional properties. And a forestry company can be expected to have extensive knowledge of how to process wood.

The question is whether wood has any material properties that make it a better fit for satellites than any alternative material. Nikkei Asia indicates that one potential advantage is that wood is transparent to many wavelengths that satellites use to communicate, potentially eliminating the need for external antennae. If said antennae would otherwise need to unfurl after a satellite reaches orbit, this could eliminate one potential source of hardware failure.

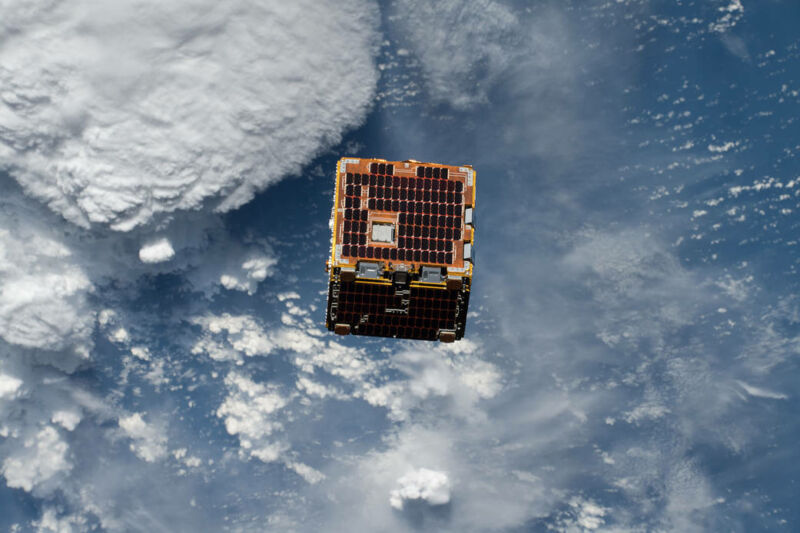

But the coverage by the BBC and others focuses on space junk. This is a real problem, as the amount of defunct satellites and random debris in low Earth orbit has created hazards for the functional stuff we’d like to keep there. Everything from scientific observatories to the International Space Station have had to be maneuvered around passing bits of junk.

Unfortunately, making satellite housings out of wood won’t help with this, for many, many reasons. To start with, a lot of the junk isn’t ex-satellites; it’s often the boosters and other hardware that got them to orbit in the first place. Housings are also only a fraction of the material in a satellite, leaving lots of additional junk untouched by the change, and any wood that’s robust enough to function as an effective satellite housing will be extremely dangerous if it impacts anything at orbital speeds.

Most of the coverage seems to present wooden satellites as helping with the space junk problem because of the fact that wood would burn up when it de-orbits. But this stuff is space junk precisely because it doesn’t de-orbit. All of our plans for handling the existing abundance of space junk involve finding a way to induce it to leave orbit. Wood won’t make any difference here.

The one point that wood might have in its favor, noted in some of the coverage and by Doi himself, is that it won’t leave much in the atmosphere if it does de-orbit and burn up. Most other hardware will vaporize into a gas of aluminum and various other metals, perhaps oxidized. Again, having a wood housing won’t eliminate these metals, given that many of them come from the satellites components and the rocket that put them in place. And, at least for the foreseeable future, this material won’t be present in the atmosphere at high enough levels to be meaningful.

Given all this, it’s completely unclear what problem wooden satellites are meant to solve. Still, the idea of figuring out how to process wood so that it would function in this context is an intriguing materials science problem, and might have some very down-to-earth applications. So, here’s to hoping that the project goes ahead regardless.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1732291