Update 8/16/2021 11 pm ET: The Biden administration has decided to recommend that most Americans get a COVID-19 vaccine booster shot eight months after their initial two-dose regimen, according to a report by the New York Times. The administration could announce the decision as early as this week and begin offering the third doses as early as mid-September, two officials familiar with the decision told the Times.

Nursing home residents and frontline health workers are expected to be first in line for the extra shots, followed by older people. The administration cited the ongoing surge in COVID-19 cases and the rampant spread of the hyper-transmissible delta variant in making their decision. Officials also pointed to data from Israel suggesting that older people vaccinated with the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine at the start of the year have since lost some protection against severe disease.

The original story follows.

Original post 8/16/2021 7:49 pm ET: Pfizer and BioNTech submitted new COVID-19 vaccine-booster data to the Food and Drug Administration Monday as US officials continue to consider whether to recommend third doses for more Americans.

For now, officials have only recommended that some people with weakened immune systems get a third dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. While officials continue to say that there is not enough evidence to support third-dose boosters for other vaccinated groups at this point, many officials say boosters will likely be in our futures. The lingering questions are when exactly shots will be needed and who will be next in line.

On Sunday, Director of the National Institutes of Health Francis Collins told the Associated Press that, with the delta variant raging and immune responses possibly waning, officials could be making decisions on boosters for this fall or winter within the coming weeks.

“There is a concern that the vaccine may start to wane in its effectiveness,” Dr. Collins said. “And delta is a nasty one for us to try to deal with. The combination of those two means we may need boosters, maybe beginning first with health care providers, as well as people in nursing homes, and then gradually moving forward” with older people and so on, essentially replicating the order of the initial vaccine rollout.

People eligible for a third dose now

Late last Thursday, the FDA amended the emergency use authorizations for both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, greenlighting third doses for some people with weakened immune systems. The very next day, an advisory committee for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—voted unanimously to recommend third doses for people who are “moderately or severely immunocompromised.”

Specifically, ACIP and the CDC recommend a third dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine (for people ages 12 and up) or a third dose of the Moderna vaccine (for people ages 18 and up) if they have:

- been receiving active cancer treatment for tumors or cancers of the blood;

- received an organ transplant and are taking medicine to suppress the immune system;

- received a stem cell transplant within the last 2 years or are taking medicine to suppress the immune system;

- moderate or severe primary immunodeficiency (such as DiGeorge syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome);

- advanced or untreated HIV infection;

- or have active treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (i.e., ≥20mg prednisone or equivalent per day), or other drugs that may suppress the immune response, such as alkylating agents, antimetabolites, transplant-related immunosuppressive drugs, cancer chemotherapeutic agents classified as severely immunosuppressive, and TNF blockers.

The CDC’s criteria do leave some uncertainty about who qualifies for a third dose. However, CDC experts in the meeting Friday noted that the recommendation is clearly not meant to apply to those with chronic conditions that result in relatively mild weakening of the immune system, such as diabetes or heart disease.

For those who qualify, the third dose should be given at least 28 days after the second dose. The third dose should be the same brand of vaccine as the person’s previous two, though the CDC said a swap was acceptable if the original brand of vaccine is unavailable.

The ACIP’s recommendations follow several studies—some published, some awaiting peer-review—suggesting that people with significantly compromised or suppressed immune systems have relatively low levels of protection and higher hospitalizations rates after a two-dose mRNA vaccine regimen. Studies also suggest that a third mRNA vaccine dose can boost protection in these groups.

Deciding to boost others

Unfortunately, there’s little to no such data for immunocompromised people who received the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine. It’s unclear how many immunocompromised people even received the shots—immunocompromised people became eligible for vaccination before the Johnson & Johnson shot was available in the US, and many doctors steered their immunocompromised patients to mRNA vaccines afterward anyway. For now, any immunocompromised people who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are stuck in a gray area with no clear vaccine guidance. Officials say they hope to have more data and guidance soon.

Officials are also eagerly reviewing data as it comes in on other groups who may need a booster shot at some point. Today, Pfizer and BioNTech announced that they submitted new data on booster doses to the FDA. The Phase I trial data suggested that a third dose, given to adults eight to nine months after their second dose, was safe and generated “significantly higher” levels of neutralizing antibodies against the original SARS-CoV-2 virus, as well as the delta and beta variants. The companies said they expect to have Phase III trial data on third doses “shortly.”

But that’s not all the data US officials will be looking at as they make decisions on potential boosters. Overall, officials will want to look at data on whether the actual protection from vaccines appears to be waning over time and/or waning against variants, such as delta. Are more people developing breakthrough infections, or are more breakthrough infections leading to severe illness? There’s also the question of whether that waning protection may vary by subpopulation, such as the elderly.

Then there’s the question of risk of exposure to COVID-19, if transmission levels are low or high at future points, and the risks of exposure to particular variants, such as delta or an as-yet unknown variant. Next is the question of whether booster shots will actually help—will they reduce breakthroughs and hospitalizations, and will they boost protection against current and future variants? Data on neutralizing antibody levels—such as the data Pfizer and BioNTech submitted to the FDA today—don’t capture the entirety of vaccine-elicited immune responses. So it’s not always clear if boosting waning or low levels will translate to more protection.

There’s also the consideration of vaccine availability in other countries. Just as the unvaccinated in the US can contribute to the emergence of new variants, countries with low vaccination coverage and high transmission levels may also see the emergence of new variants that can spread globally.

Current data on vaccine efficacy

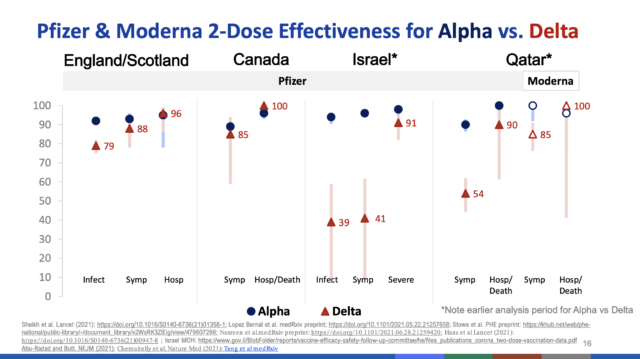

To date, data suggests antibodies from COVID-19 vaccines persist for at least six months. At six months, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine has shown 91 percent efficacy against symptomatic infection and 97 percent efficacy against severe disease. Moderna reported 93 percent efficacy against symptomatic infection at six months. Various real-world data from other countries suggests that vaccine efficacy is reduced by the delta variant but still substantial against infection and very high against severe disease and death.

Preprint and unpublished data from Israel suggest higher rates of breakthrough infections as more time passes since vaccination. For instance, one study of a cohort of 33,993 fully vaccinated adults found the rate of breakthrough infections was lower in those fully vaccinated less than five months ago (1.1 percent) compared with those vaccinated longer than five months ago (2.4 percent). The risk of breakthrough infections also increased by age group.

For now, it’s unclear what officials will see as the threshold for recommending booster shots. When a decision is made, Biden administration officials have been clear that they’ll be ready to quickly provide vaccine supplies to those who need them. Still, some people aren’t waiting for the official green light. According to an internal CDC document viewed by ABC News, the agency estimates that 1.1 million people have already gotten a third dose. And the number of people getting a booster ahead of recommendations may only increase as third doses are offered to people who are immunocompromised. People eligible for a third dose do not have to show any proof of their immune status; third doses will be administered based on the honor system.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1787625