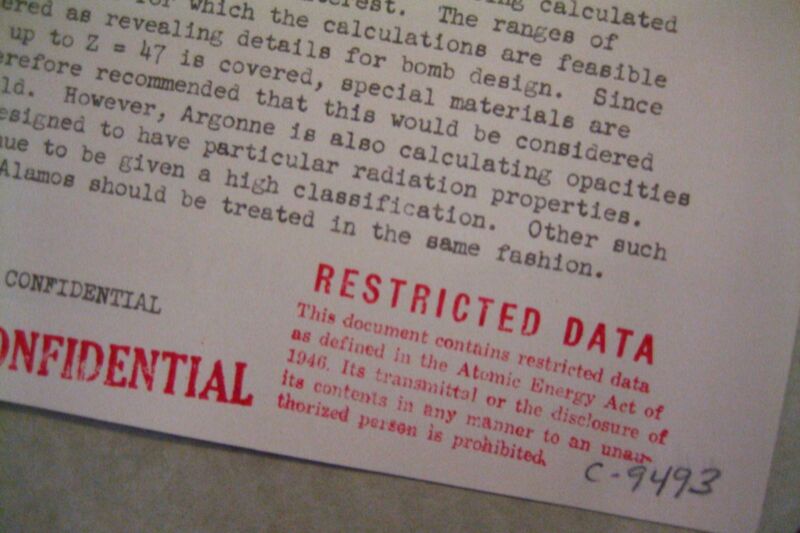

The revolutionary discovery of nuclear fission in December 1938 helped launch the Atomic Age, bringing with it a unique need for secrecy regarding the scientific and technical underpinnings of nuclear weapons. This secrecy evolved into a special category of proscribed information, dubbed “Restricted Data,” which is still in place today. Historian Alex Wellerstein spent over 10 years researching various aspects of nuclear secrecy, and his first book, Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States (University of Chicago Press), was released earlier this month.

Wellerstein is a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey, where his research centers on the history of nuclear weapons and nuclear history. (Fun fact: he served as a historical consultant on the short-lived TV series Manhattan.) A self-described “dedicated archive rat,” Wellerstein maintains several homemade databases to keep track of all the digitized files he has accumulated over the years from official, private, and personal archives. The bits that don’t find their way into academic papers typically end up as items on his blog, Restricted Data, where he also maintains the NUKEMAP, an interactive tool that enables users to model the impact of various types of nuclear weapons on the geographical location of their choice.

The scope of Wellerstein’s thought-provoking book spans the scientific origins of the atomic bomb in the late 1930s all the way through the early 21st century. Each chapter chronicles a key shift in how the US approach to nuclear secrecy gradually evolved over the ensuing decades—and how it still shapes our thinking about nuclear weapons and secrecy today.

Along the way, we meet such pivotal figures as Vannevar Bush and James Conant, as well as famous Manhattan Project scientists like Robert Oppenheimer, embedded journalist William Laurence, and notorious Soviet spies Klaus Fuchs and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Wellerstein delves into the establishment (and eventual dissolution) of the post-war Atomic Energy Commission, the emergence of the Cold War, and how attempts to reform the system failed (due in part to partisan politics), leaving the US with an outdated nuclear secrecy policy that is arguably not especially effective.

“One of the things that makes American nuclear secrecy so interesting is that it sits at a very interesting nexus of belief in the power of scientific knowledge, the desire for control and security, and the underlying cultural and legal values of openness and transparency,” Wellerstein writes in his introduction. “These at times mutually contradictory forces produced deep tensions that ensured that nuclear secrecy was, from the beginning, incredibly controversial, and always contentious, and we live with these tensions today.”

Ars sat down with Wellerstein to learn more.

Ars Technica: Why is there still so much interest in this period of US history?

Alex Wellerstein: I think there is an inherent draw toward nuclear weapons because of their power and their persistence. Even if we got rid of all of them tomorrow, we would still be fascinated with their history and their development because they represent some level of the maximum that we as clever creatures can accomplish, for both good and for ill. The Cold War feels like it’s further away from us, but we still live in a world that’s shaped by it, and it really wasn’t that long ago. We had the historical conditions that led to these states building massive nuclear arsenals, doing so with huge amounts of secrecy around them, knowing that if they ever use these weapons, it could potentially be catastrophic. I think it’s very telling about human beings and the types of creatures we are.

Ars Technica: A major theme running throughout your book is the tension between the need for secrecy and the ideal of free and open science.

Alex Wellerstein: You cannot make these weapons without relying heavily on advanced scientific input. Scientists typically share an ideology that developed over the 19th and 20th centuries about what it means to be a scientist. It usually does not mean that they want to be technicians; they actually look down on technicians and engineers—people they see as being simply transactional in their knowledge, people who are just fulfilling a role. The scientists, especially the physicists, look at their job as being explorers of the natural world. They often identify not along national lines but on professional lines. They see themselves as being apart from the world to some degree.

So you have these conflicting desires, even within individual people. I spent a lot of time in the book talking about Leo Szilard. I like him as a character because he was, in certain ways, really conflicted. He believed in the openness of science. He did not believe that military secrecy is a good thing; he thought that it would be misused. He believed scientists need to have total freedom of movement. At the same time, he also was terrified of the Nazis. So he had to try to come up with ways of reconciling these two impulses, which ultimately left him pretty unsatisfied because there really isn’t a great way to reconcile them.

Ars Technica: Many Jewish physicists fled Nazi Germany and occupied countries and ended up working on the Manhattan Project. That experience couldn’t help but color their perceptions.

Alex Wellerstein: It’s not even that many as a proportion, but their impact is extremely disproportionate. That’s not a coincidence. If your project requires people who really take the threat seriously, there’s nobody who takes the threat of a Nazi atomic bomb more seriously than Jewish refugees from Nazism. Somebody who’s a native-born American might say, “Well, I don’t know what the odds are that it’s possible.” These are the people who are going to say, “It doesn’t matter if there’s a low chance because the consequences are unimaginable. This is not some petty squabble with a fool. This is a genocidal experience. And if you don’t get your act together, it’s going to come for you, too.”

It’s also part of the answer to why so many of the spies were Jewish—because of the history, especially in New York City, of Judaism and communism. This was a time in which many of the Jews felt that the United States and the capitalist world were not doing enough to combat fascism, so [Stalin] looked like a viable alternative.

Ars Technica: Just how extensive were the spy networks?

Alex Wellerstein: We’ve learned a lot more about the spies in the last 15–20 years, including the size of the Soviet spying effort, partially through the release of the Venona transcripts, which are intercepted Soviet decrypts. There were so many communications from World War II that were decrypted after and revealed the existence of these spy networks. And there has been at least one major case of a former Soviet agent grabbing all of his old books and [defecting] to the United States, which gave the codenames of everybody who was in the Venona transcripts.

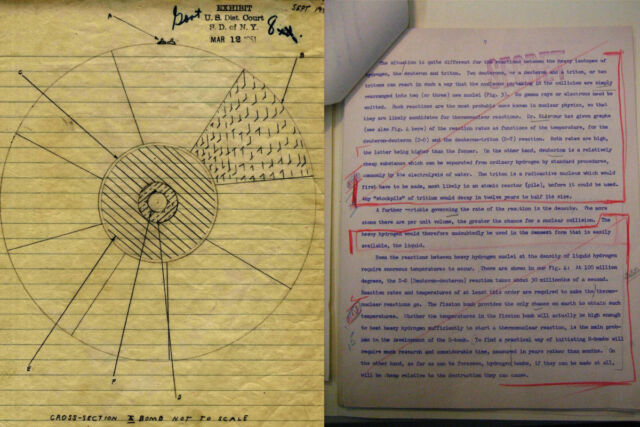

As far as we can tell, there were zero spies for Nazi Germany in the Manhattan Project, zero spies for Japan, zero spies for Italy. The Soviet spy apparatus in the United States consisted of several hundred people in different roles, maybe 10 of whom were connected in some way to the Manhattan Project. Of those 10, two or three at Los Alamos actually knew very much. And of those, Klaus Fuchs was the only one with deep connections. Through him, you got David Greenglass and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Fuchs could give the Russians detailed diagrams, with measurements, of every part in the bomb.

There were probably at least 10,000 scientists working on the Manhattan Project out of a total labor pool of 500,000 people, so having one crucial spy is not very surprising. They were so preoccupied with other things, that really wasn’t what they were worried about. In the book, I describe it as an impossible mandate because it’s literally impossible to imagine screening out those people and not having one of them slip in under the radar. With Fuchs, they didn’t screen him at all because he was part of the British delegation, so he basically got a free pass. If they had looked closely at him, they probably would have raised some questions about what he was doing and what his political views were.

There was an event for the 70th anniversary of the Manhattan Project at the Atomic Heritage Foundation a couple of years ago. A physicist named Ben Bederson spoke; he was bunkmates with David Greenglass in the same special engineering detachment. He said, “Oh, Greenglass was obviously a [communist], he talked about it all the time. I tried to get transferred out of his bunk because he was so annoying. He never tried to recruit me, but he assumed that because I was from the same part of New York as he was, that I had similar opinions because I was Jewish. If anybody had ever asked me once, ‘Are there any communists in here?’ I’d have said, ‘Obviously, David Greenglass.’”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1760295