A new DNA analysis of stains on a silk shawl that may have belonged to one of Jack the Ripper‘s victims concluded that the killer was a Polish barber named Aaron Kosminski, according to a paper published last week in the Journal of Forensic Sciences. But other scientists are already calling into question the paper’s bombshell conclusions—and they’re not exactly mincing words.

Finally putting to rest the identity of one of history’s most notorious killers would indeed be very big news, especially for true-crime buffs who have followed the Ripper saga for years (so-called “Ripperologists”). The problem is, we’ve been here many times before. This is just the latest claim to have “proof” of Jack the Ripper’s true identity, and while it has all the trappings of solid science, the analysis doesn’t hold up under closer scrutiny. Several geneticists have already spoken out on Twitter and to Science magazine to point out, as Kristina Killgrove writes at Forbes, that “the research is neither new nor scientifically accurate.”

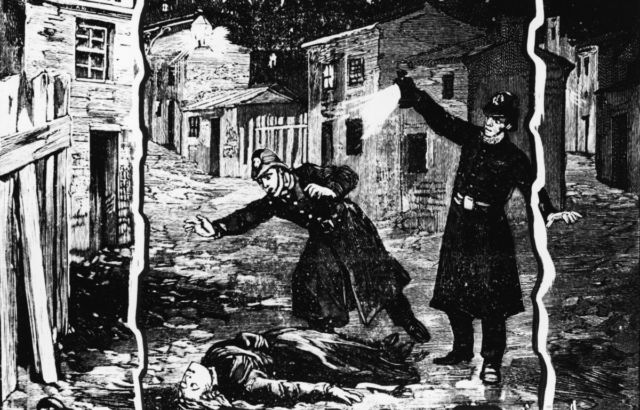

On August 31, 1888, police discovered the body of Mary Ann Nichols in Bucks Row in London’s Whitechapel district. Her throat had been cut and her abdomen ripped open. Over the next few months, a serial killer who came to be known as Jack the Ripper would use the same method to kill four women: Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. And then, as abruptly as they began, the murders stopped. (These are the “canonical five.” Other murders sometimes attributed to the Ripper are inconclusive.)

The murders remain unsolved in terms of the Ripper’s true identity. Kosminski, who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, is a frequently suggested suspect, since he was committed to an asylum right around the time when the murders suddenly ceased. But FBI criminal profiler John Douglas noted in his 2001 book, The Cases That Haunt Us, that if Kosminski had been the Ripper, he would likely have boasted of the killings during his incarceration, and there’s no evidence he did so.

Other men on the potential Ripper list include a barrister named Montague John Druitt; Queen Victoria’s physician, Sir William Withey Gull; Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale; and author/mathematician Charles Dodgson, aka Lewis Carroll. In her 2002 nonfiction book, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper—Case Closed, crime novelist Patricia Cornwall described her own years of research, concluding that a German-born artist named Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper. Despite its optimistic title, Cornwall’s treatise failed to convince her critics; nor did her 2017 follow-up, Ripper: The Secret Life of Walter Sickert.

So there’s a long history of people claiming to have made the definitive identification of Jack the Ripper. This latest analysis, by Jari Louhelainen of Liverpool John Moores University and David Miller of the University of Leeds, focuses on a shawl that supposedly belonged to Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes. Author Russell Edwards bought the shawl at auction in 2007 and supplied it to the authors for analysis. His 2014 book, Naming Jack the Ripper, relied on that then-unpublished work to claim Kosminski as the Ripper. (Edwards reportedly became interested in “solving” the Ripper murders—and cashing in on Ripper-mania in the process—after watching the 2001 film From Hell.)

“How did this ever get past peer review?”

While the authors claim this is “the most systematic and most advanced genetic analysis to date regarding the Jack the Ripper murders,” their work has not been well received, either back in 2014 or now. Geneticist and popular-science writer Adam Rutherford, author of A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived (among other tomes), interviewed Louhelainen at the time of the book’s publication for BBC Inside Science. “I asked him if this evidence would stand up in court if the murder had taken place recently, and he said ‘no,'” Rutherford tweeted. “So why do we even vaguely consider that 130 years later it would be valid?” Turi King, a geneticist at the University of Leicester, whose team did the genome sequencing of Richard III, called the new paper “unpublishable” on Twitter, asking, “How did this ever get past peer review?”

One issue is the lack of conclusive proof that the silk shawl in question actually belonged to Eddowes—or, even if it did, that she was wearing it when she was murdered. The authors state that it is “purportedly linked” to Eddowes, but that provenance is questionable, according to both Rutherford and King. Furthermore, the authors merely “hypothesize” that the stains are related to blood spatter from the victim and semen from the killer.

Both Rutherford and King noted that the silk shawl has been handled extensively over the years by lots of people who did not take the slightest precautions to avoid contamination (i.e., wearing gloves), and those people included the same descendants of Kosminski whose DNA was used for the comparison in the study. So despite the authors’ good-faith attempt to exclude the DNA of contemporary people, the shawl has already been hopelessly tainted.

Then there’s the authors’ use of mitochondrial DNA for their analysis, i.e., DNA that passed from a mother to her children. That might work to link Eddowes with her maternal descendants but not for the descendants of Kosminski. “The suspect couldn’t have passed on his mitochondrial DNA, as he was a man,” King tweeted. “And yes, I know [about] that recent publication of rare set of cases.” Furthermore, “Based on mitochondrial DNA one can only exclude a suspect,” Hansi Weissenberger of Innsbruck Medical University told Science.

Walther Parson, a forensic scientist also at Innsbruck Medical University in Austria, questioned the authors’ decision not to include the specific genetic variants used for their analysis in the paper, opting instead for a public-friendly graphic using colored boxes to illustrate where DNA sequences overlapped. The authors cite the UK’s Data Protection Act as their rationale, but Parson said publishing mitochondrial DNA sequences isn’t a privacy risk. “I wonder where science and research are going when we start to avoid showing results but instead present colored boxes,” he told Science.

Biologist Jerry Coyne raised similar criticisms on his blog, although he was initially a bit less scathing in his evaluation of the claims. “The data, at least in the weak form presented here, increase the likelihood that Aaron Kosminski, who was a suspect in the murders, was the killer,” he wrote. “But we’re a long way from knowing who butchered those five women. Caveat lector.” He later posted a lengthy critique supplied by Rutherford, however.

Rutherford is confident the identity of Jack the Ripper “will never be known” and reserved some of his harshest criticism for media coverage of the paper, which he felt lacked skepticism and was hence irresponsible. “This is terrible science and terrible history,” he said on Twitter. “It doesn’t warrant discussion in the press, let alone in an academic journal. Nonsense like this paper and a gullible media does nothing but foment scientific and historical illiteracy built upon the grotesque romanticization of the brutal murders of five women. And we should all try harder to be better than this.”

DOI: Journal of Forensic Sciences, 2019. 10.1111/1556-4029.14038 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1475945