NASA has released two more images made from data collected by the James Webb Space Telescope, and they reveal incredible detail about the largest planet in the Solar System.

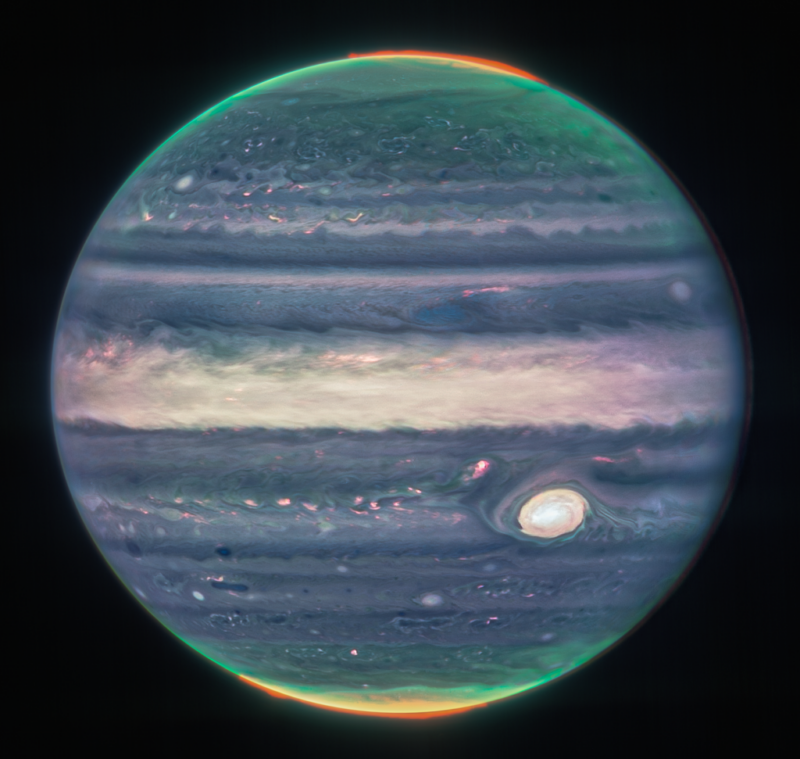

The data used to process the images was captured in late July using the telescope’s Near-Infrared Camera, which observes light at wavelengths slightly longer than those at the red end of the visible spectrum. By observing Jupiter at these wavelengths beyond visible light, the powerful space telescope is able to tease details of the planet not previously observed.

One of the photos, in particular, showcases the auroras at both poles that result from Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field. The colors in these images are false—because infrared light is invisible to the human eye, the light has been mapped onto the visible spectrum. The auroras shine in a filter that is mapped to redder colors due to their emission of ionized hydrogen.

Jupiter’s “Great Red Spot” also stands out in the new images, although it appears white rather than reddish. This white color indicates reflectivity from high-altitude cloud tops.

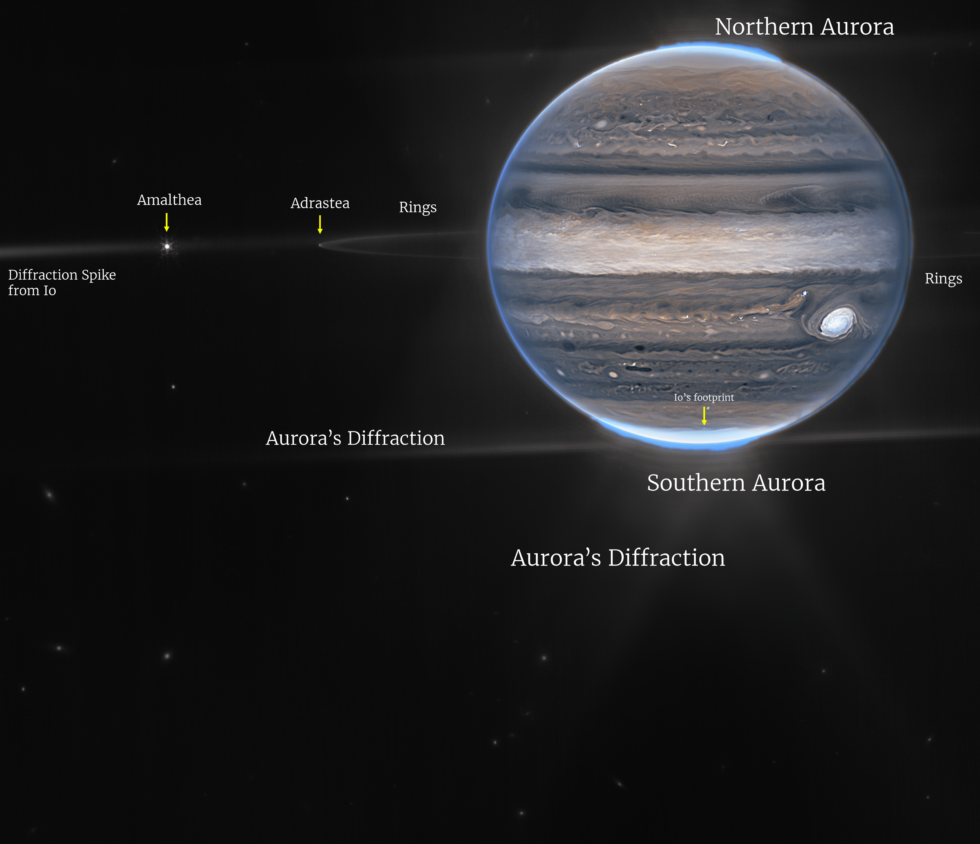

A second image provides a wider view of the Jovian system and includes perspective on the planet’s thin rings, two of its small moons, and the extent of its auroras. The rings are exceptionally difficult to observe from afar, as they are 1 million times fainter than the planet. Distant galaxies are also visible in the background.

Imke de Pater, professor emerita of the University of California, Berkeley, led Webb’s scientific observations of the planet along with Thierry Fouchet, a professor at the Paris Observatory.

“We hadn’t really expected it to be this good, to be honest,” she said in the news release accompanying the images. “It’s really remarkable that we can see details on Jupiter together with its rings, tiny satellites and even galaxies in one image.”

Why has it taken so long for these images to be processed? The simple answer is that the James Webb Space Telescope does not take photographs with its large mirrors that can simply be transmitted back to Earth. Rather, raw light brightness data from Webb’s detectors is sent to the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. Scientists, including NASA researchers, translate that data into images, the best of which are publicly released.

This data repository is public, however, and citizen scientists can use this data to process images as well. In the case of the new Jupiter images, Modesto, California-based Judy Schmidt did this processing work. For the image that includes the tiny satellites, she collaborated with Ricardo Hueso, who studies planetary atmospheres at the University of the Basque Country in Spain.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1875271