The pickup truck was so overloaded with medical equipment that the chassis sagged almost to the ground. Dr. Austin Demby had just finished loading up the Toyota Hilux with as many microscopes, IV bags, computers, and lab and chemistry equipment he could fit in the extended bed. And as fast as possible, he sped away from the hospital in Segbwema, Sierra Leone.

Literally under gunfire, Demby and his colleagues were fleeing the Revolutionary United Front, a violent and destructive rebel army. It was 1991, and a brutal civil war had just erupted, putting the staff at Nixon Memorial Methodist Hospital at extreme risk. So, they were evacuating.

Darting along the muddy roads, they drove into a deep pool of rainwater. Suddenly, the truck stalled. They opened the hood but couldn’t figure out what was wrong. The battery seemed fine.

“I just went back in and prayed and turned it and it quickly fired up and I just put my foot on the pedal and zoomed out of there,” Demby told Ars. They drove about 40 kilometers to Kenema, Sierra Leone’s second largest city, but they weren’t there for long. “We couldn’t stay because Kenema was slowly being surrounded, and so I moved my staff and the US-government supported program out of the country.”

Since 1976, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had been running a Lassa fever research program in Sierra Leone, which Demby began directing in 1987. Lassa is a viral hemorrhagic fever closely related to Ebola, characterized by rare, but severe, vascular leakage—a clinical way of saying the body is so overwhelmed with fluids that it begins to leak blood from every orifice (yes, mouth, eyes, anus, vagina, etc.). It’s difficult to detect, deadly, highly contagious, and has no vaccine.

Lassa, which is endemic to West Africa, is somewhat of an ignored, forgotten disease. While news of Ebola outbreaks regularly splash headlines, Lassa is fairly unknown, despite annually infecting around 300,000 people and killing 5,000 per year. Little was known about the virus, named for the Nigerian village where it originated in 1969. The CDC had accomplished much in the prior 15 years, such as learning how to better detect and manage infections, but Demby and his team had to flee an even more deadly virus: war.

“It’s not running away,” Demby said. “We’d done quite a bit. It was just not safe to be there at that point, so turning over the skills, assets, and all of the equipment and supplies that we had to the host government was the right thing to do.”

Yet, amidst the chaos and violence and disease, one man stayed behind. His name was Dr. Aniru Sahib Sahib Conteh, a modest physician from Sierra Leone. With few resources and a skeleton crew, Conteh would spend the next 11 years treating Lassa patients in the middle of one of his country’s—heck, history’s—most horrific war zones.

Decades later, it’s clear Conteh’s work helped revolutionize the way Lassa is diagnosed and treated, and his persistence amidst civil unrest and human rights violations provided a framework for others battling hemorrhagic fevers and emerging diseases in some of the world’s most in-need environments. By one estimate, Conteh’s work reduced Lassa mortality by 20 percent. He saved countless lives. He even housed refugees in his own home.

However, not long after the war finally ended, an accidental needle prick led to Conteh’s own Lassa infection. He eventually succumbed to the disease that he had dedicated his life to fighting. But while Conteh and the virus that killed him are widely unknown, his example continues to inspire others and shape the approach to fighting devastating viral outbreaks in Africa and beyond.

-

Dr. Conteh (white polo, third from right) stands with his staff at the Lassa Ward. Ross Donaldson (far right) would later write up the experience in a book.Ross Donaldson

-

Outside the Lassa Ward in Kenema.Ross Donaldson

-

Here’s the protective clothing staff at the ward would utilize during Donaldson’s time there.Ross Donaldson

-

Educating the public about Lassa is a consistent means to battle the disease.Ross Donaldson

Danger within the dangers of war

The Sierra Leone Civil War broke out in March 1991, as the Revolutionary United Front attempted to overthrow President Joseph Momoh, a former major-general who won a 1985 election in which he was the lone candidate. Momoh inherited a profoundly corrupt and nearly bankrupt government, leading him to slash health and education budgets. An uprising soon followed.

Led by ex-army corporal Foday Sankoh, the RUF were notoriously vicious, spreading sexual violence, torture, mutilation, and indiscriminate death throughout the small West African region. They were aided by Charles Taylor, a guerrilla leader and war criminal instrumental in another civil war in nearby Liberia, one that started two years earlier.

In turn, Taylor received cash and guns from numerous outside groups, including Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi; Blaise Compaoré, president of Burkina Faso; and Viktor “Merchant of Death” Bout, a notorious Russian arms dealer. Blood diamonds abundantly mined throughout the lush landscape also played a key role in financing the brutal conflict. (Yes, the Leonardo DiCaprio thriller Blood Diamond takes place during this time.)

The RUF recruited child soldiers, amputated limbs, and massacred civilians without restraint. Some rebels would bet on the sex of unborn babies, then eviscerate the pregnant mothers with machetes to determine the winner. They looted and destroyed any government or medical building they came across, including the Methodist hospital Demby called home at the time. When the dust settled in 2002, the war had killed around 70,000 and displaced 2.6 million people, roughly half the population, according to a United Nations report.

After fleeing the hospital and with nowhere to go, Dr. Conteh spent months wandering the countryside, hungry and fearful. Eventually, he wound up in Kenema and began treating war victims at a small clinic. He often considered escaping, perhaps fleeing to Nigeria or elsewhere. He was a skilled doctor who could easily find work somewhere, anywhere else.

“But how could I leave?” Conteh told one of his students, Ross Donaldson, as outlined in Donaldson’s book, The Lassa Ward. “My people, they had no one to help them.”

After Conteh diagnosed a patient with Lassa, paranoid medical staff at the makeshift clinic began referring all Lassa patients to the doctor. He was the only one willing to treat the disease, which he had become intimately familiar with after joining the CDC’s Lassa team in 1979. Conteh trained a few nurses with donated supplies and borrowed money, and, in 1991, he soon opened the world’s only Lassa fever isolation ward.

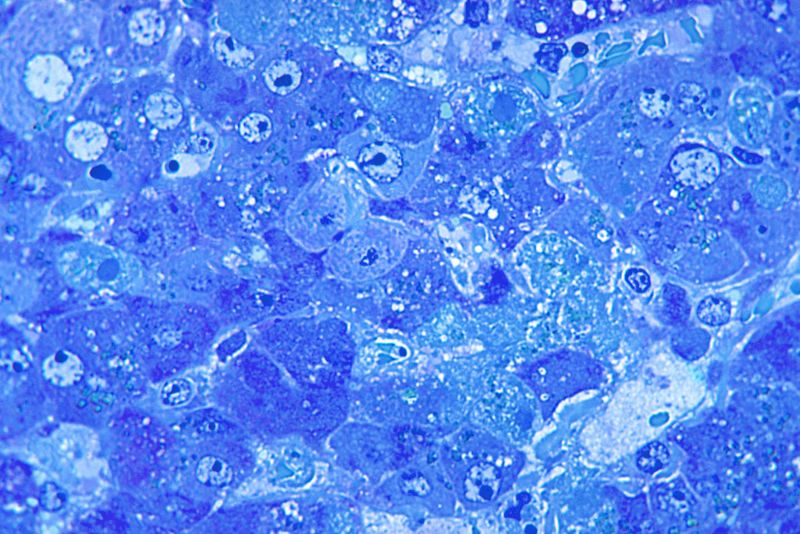

The grounds at Kenema Government Hospital were (and largely remain) a scattering of one-story buildings in a gravel courtyard. The Lassa ward was a small outlying concrete compound encircled by a tall barbed wire fence pegged with warning signs. Generator powered, the building had few rooms and as few windows. The smell of bleach and blood was omnipresent.

Medical staff working elsewhere avoided the ward, its patients, and its doctors as if it were a leper colony. The lab was so primitive it didn’t even have the capacity to actually confirm Lassa cases—Conteh was forced to rely on his intuition, but few, if anyone, knew the disease better than he.

It was a far cry from the fortified biosafety level 4 labs that typically analyze viruses like Lassa. Instead of positive pressure protective suits, the bulbous astronaut-like outfits standard for handling deadly substances, staff at the Lassa ward wore two pairs of gloves, surgical gowns, eye goggles, and a face mask. The nurses’ hand washing station was a table and two buckets. Yet, it was all that could be done, and under Conteh’s administration, the earnest efforts saved the lives of untold thousands.

By 1996, a big portion of funding for the ward came from Medical Emergency Relief International, or Merlin, a British non-profit health charity specializing in conflict zones. Nearly a decade later, Conteh would become the first recipient of the organization’s Spirit of Merlin Award to honor people who exemplified its values. Nicholas Mellor, one of the organization’s co-founders, doesn’t specifically remember how the NGO learned of Conteh’s operation. But in these kinds of situations, he says, there aren’t many medical healthcare workers left to begin with.

“At that particular time, there was only one anesthetist in the whole of the country,” Mellor said in a call with Ars, describing West Africa as “the world’s Achilles heel” for these emerging infections. “You are very much the last person standing in these kinds of places.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1444729