It’s September 1915 in Greenfield, Ohio, a small town located on the Paint Creek between Columbus and Cincinnati. At a time of year when summer’s warmth gives way to autumn’s chill, a change of another sort occurs in a small factory on N. Washington St.: the first Patterson-Greenfield Automobile is completed and readied for sale. It’s a major milestone, not just because this vehicle comes from a first-time automaker.

There have been more than 1,900 automobile manufacturers in the United States since the Duryea Motor Wagon Company sold its first automobile in Springfield, Mass. in 1896. Yet in the explosion of entrepreneurship that followed, only one American automaker has been founded and run by a Black individual: C.R. Patterson & Sons of Greenfield, Ohio.

In some ways, Patterson’s fate was typical of many small-town, small-time automotive manufacturers—the business found some modicum of success though never rose to the same heights as the auto brands we still know in 2021. Yet, in retrospect this Black-owned business had quite a run. The team behind C.R. Patterson & Sons worked its way through 74 years, three generations, and multiple changes in business strategy at a time of technological change and extreme prejudice, making the company’s story all the more remarkable.

Life before the wheel

Charles Richard Patterson was born into slavery on a Virginia plantation in 1833, the first of 13 children. Little else is known about his life there, and the same goes for how he and his family gained their freedom.

But eventually, around 1850, the Pattersons came to settle in Greenfield, Ohio. The town was already known for its strong abolitionist sympathies thanks to Rev. Samuel Crothers, the founder of the town’s First Presbyterian Church. With First Presbyterian, Crothers established one of Ohio’s—and the nation’s—earliest abolition societies in 1833. And before long, Greenfield became a stop on the Underground Railroad, and a magnet for Black slaves seeking freedom.

Here, the Pattersons eventually worked as blacksmiths, a common skilled trade for former slaves during a period when occupations commonly held by white individuals were closed off. By 1864, Patterson had become successful enough to woo and eventually marry Josephine Outz of Greenfield. Six children followed.

Like many blacksmiths, Patterson’s career led him to work for local carriage maker Dines & Simpson, where he became foreman, working side-by-side with white workers and supervising others. But Patterson wanted to start his own business. Looking back, it’s easy to perceive that as an impossible goal with insurmountable hurdles given the lack of financing available to aspiring Black businessmen and the general prejudice behind many policies of the day.

Nevertheless, Patterson ultimately partnered with J.P. Lowe, a white man, and they established J.P. Lowe and Company in 1873. The company soon earned the same reputation Dines & Simpson had enjoyed for constructing high-quality products. Lowe and Company grew a wholesale business supplying carriages to Cincinnati-area retailers and other regional customers.

As the business grew, so did Patterson’s community involvement. He was a trustee of the Greenfield African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1880, where he also taught Sunday school. Patterson was also active in the Cedar Grove Masonic Lodge No. 17 from 1871 through 1899. Patterson filed suit against the local Board of Education when his son was denied admission to all-white high school, a case he ultimately won.

Given his high profile locally, it’s no surprise that by 1888, the company employed 10 men, according to Ohio’s Bureau of Labor Statistics Report. It was a successful partnership that lasted until 1893, when faraway events would change Patterson’s life.

A not great Depression

The economy had been improving as 1892 ended, a notion reinforced by a myriad of economic business indicators. Unfortunately, there were signs the party was ending. Monthly indicators, such building construction and railroad investment, began to decline. In January, the failure of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, one of America’s largest employers, ignited panic on Wall Street, causing a run on banks. Needing deposits to feed the run, banks called in business and agricultural loans. But both sectors had become wildly overextended, leading to numerous bankruptcies, a drastic reduction in America’s gold supply on which the dollar was based, and a realignment of America’s political priorities.

The result was a four-year depression: the Panic of 1893. It was one of America’s worst depressions, and businesses in Greenfield, Ohio were not immune.

“The older firm of Lowe and Patterson, once extensive, dwindled through business depression to such proportions that the formation of the present partnership was opportuned and consummated,” Patterson later recalled during a speech at the first meeting of the National Negro Business League in 1900.

Now sole proprietor of the renamed C.R. Patterson & Sons, Patterson would soon bring his sons into the business. According to Christopher Nelson’s history of the family, The C.R. Patterson and Sons Company: Black Pioneers in the Vehicle Building Industry, 1865–1939, Frederick would graduate high school as a Valedictorian, entering Ohio State University in 1889. (He became the first Black player on the Ohio State University football team and served as class president in 1893.) He quickly joined the company beside his brother Samuel and their father before a few years of major family events changed things for Frederick. In 1899, Samuel died unexpectedly. Two years later, the younger Patterson married Betty Estelline Postell, and the couple would have two children who would also become part of the Patterson & Sons company: Frederick Jr. and Postell.

Victorian state-of-the-art

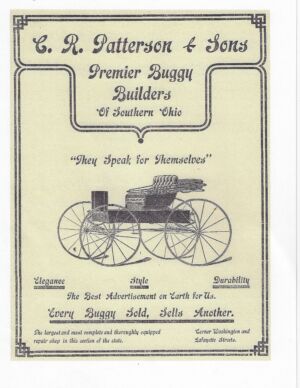

By the turn of the century, Patterson’s integrated workforce averaged some 35-to-50 employees strong. They produced 28 carriage models priced from $120 to $150 and also made specialty vehicles, such as the Mail Delivery Buggy and the School Wagon. However, their most popular offering was the Doctor’s Buggy—hardly surprising given the company’s targeted advertising strategy. Aside from appearing in their local newspaper, ads for Patterson buggies regularly appeared in “The Journal of the National Medical Association,” selected Black magazines including “Alexander’s,” and “The Crisis,” and a regional agricultural publication called “The Ohio Farmer.”

Patterson did not consider his shop one that merely assembled parts built by other companies. At the same time, Patterson & Sons was not large enough to mass-produce carriages, like Studebaker had done for most of the 19th Century. No, this was a custom shop where craftsmanship was good enough for the company to offer a two-year warranty on its vehicles.

Among some of Patterson & Sons’ details: The wood used was seasoned for three years in the company’s yards, with ash frames and poplar panels. Bodies weighed as little as 30 pounds, yet boasted a 600-pound payload. Shafts were constructed from black hickory, and the wheels came from elm and white hickory. Rubber tires could be ordered to replace the steel rims commonly used.

The quality of the company’s products sustained business even after the initial arrival of the automobile. In fact, it took a full decade into the 20th century before Patterson & Sons felt any economic impact. The year 1910 proved to be a turning point—C.R. Patterson died. Frederick, already heavily involved with designing and building of their products, took over management of the firm.

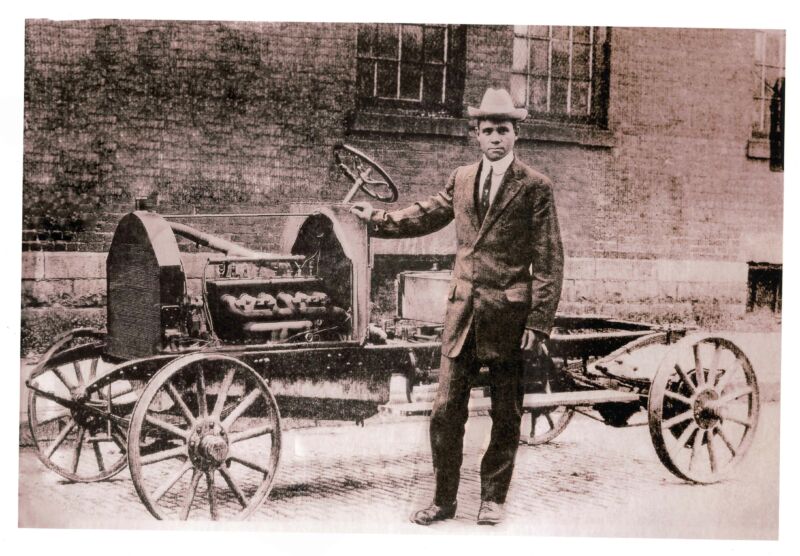

Unlike today, where there are 1.88 vehicles per household according to the US Department of Transportation, at this point in the US there was one car for every 800 people; that’s up from one car for every 65,000 people eight years before. During that time, Patterson & Sons had already built up a side business of servicing automobiles—something that wasn’t unusual in the early days of motoring. Initially, this involved restoring paint and upholstery, but eventually the work included electrical and mechanical jobs. Frederick Patterson knew that the time had come for his carriage company to do what so many others had already done—build a horseless carriage.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1747991