Plenty has happened since Ars last took a moment to outline the legal mishegas involving Defense Distributed, its founder Cody Wilson, and the future of 3D-printed guns.

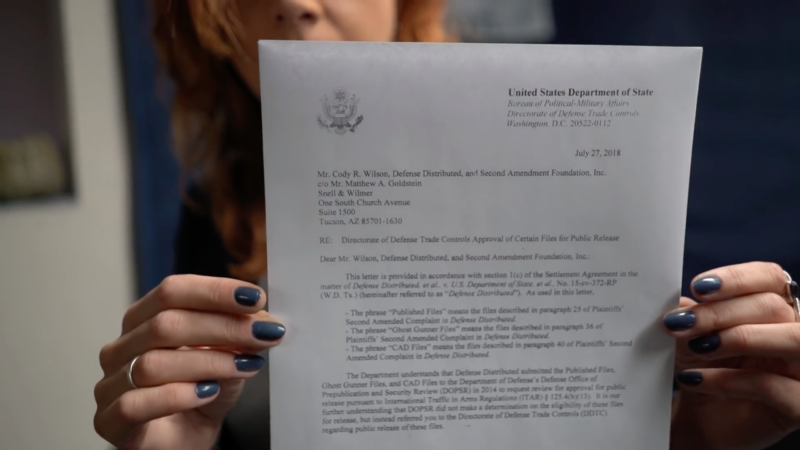

After a surprising settlement with the Department of Justice in summer 2018 ended a five-year legal battle, Defense Distributed finally had the go-ahead to legally publish its 3D-printable firearms CAD files online. Wilson initially announced the files would be restored on August 1, 2018—but he put them up early, on July 27.

Within days, several US states sued to stop the distribution. On July 31, a federal judge in Seattle granted a “temporary restraining order” (TRO) preventing Defense Distributed from further publishing its 10 firearms files. Wilson and Defense Distributed complied.

The move also prompted Defense Distributed itself to preemptively sue the state of New Jersey in an attempt to try to stave off further legal pressure.

Despite the legal hullabaloo, even Wilson acknowledged that the files were not substantively different from ones that had circulated on BitTorrent for years—nor were they different from ones that continue to be available through various mirror sites.

At the end of August, Wilson arranged Defense Distributed’s first official press conference at an Austin hotel. In an effort to comply with the TRO, the then-CEO announced that, rather than give the files away for free, Defense Distributed would sell them, pay-what-you-want style, for a “suggested price” of $10.

The files would not be available directly online; rather, they would be delivered via a Defense Distributed-branded flash drive sent by mail. (Ars successfully bought one.)

-

Ars ordered a Defense Distributed USB drive the day after the initial Wilson news broke; it arrived by the weekend (though Wilson’s name was still attached to the company at that time).Nathan Mattise

-

On September 19, APD’s Cmdr. Troy Officer spoke to the press about a new warrant regarding child sexual assault allegations against Defense Distributed founder Cody Wilson. The alleged incident took place on August 22, days before Wilson held his first Defense Distributed public press conference.Nathan Mattise

Less than three weeks later, this legal back-and-forth was bumped from the headlines by a separate Wilson saga. In late September 2018, the Austin Police Department unexpectedly issued an arrest warrant for Wilson, who was accused of sexually assaulting an underage teenager on August 15. The alleged incident took place just weeks before the Defense Distributed press conference.

Authorities soon laid out a narrative substantiated by what they described as testimony from the girl and hotel, parking, and video records.

Local police didn’t have Wilson in custody, however, because the firearms activist was overseas in Taiwan. Wilson skipped his return flight after authorities believe he was tipped off about the accusations. Through an international effort, Wilson was eventually taken into custody in Taipei and escorted back to Texas, where he was booked then quickly released on bond.

The incident led Wilson to resign from his own company despite Defense Distributed’s increasingly heated legal battles. Suddenly, those efforts against various state attorneys general would be led by an unlikely new leader, Paloma Heindorff. A British woman with a background in the arts rather than weaponry, she had worked at Defense Distributed for three years. By her own admission, she had never even shot a firearm before 2015.

Today, three primary cases involve either Wilson or Defense Distributed: State of Washington et al. v. Department of State et al, which is underway in federal court in Seattle; Defense Distributed v. Grewal et al, which is pending in federal court in Austin; and State of Texas v. Cody Wilson, which is just starting to unfold in Travis County court, also in Austin.

What has happened in these cases so far, and how are they related—or not? Perhaps more importantly, what are the stakes for Defense Distributed and for the distribution of its CAD files? Let’s break down the situation.

The case is moving ahead at a normal, methodical pace.

On August 28, 2018, US District Judge Robert Lasnik granted the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction—in essence, mandating that Defense Distributed cannot publish its relevant CAD files.

“It is not clear how available the nine files are: the possibility that a cybernaut with a BitTorrent protocol will be able to find a file in the dark or remote recesses of the Internet does not make the posting to Defense Distributed’s site harmless,” he wrote.

As Ars previously reported, the judge also found that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed based on their argument that the Department of State, in allowing for a modification of federal export law, had unwittingly run afoul of a different law, the Administrative Procedure Act.

In essence, the judge concluded that, because the Department of State did not formally notify Congress when it modified the United States Munitions List, the previous legal settlement that Defense Distributed struck with the Department of State—which allowed publication of the files—is invalid.

Since then, no substantive rulings have been issued.

In mid-November, the federal defendants asked for the case to be put on hold for four months while the State Department considered new rules that “will directly bear on this case.” In a filing, government lawyers explained that if the State Department goes ahead with its proposed final rule, there will be no question that Defense Distributed can legally publish its files.

In early December, the plaintiffs began the process of civil discovery—trying to force Defense Distributed to hand over relevant materials related to the company’s support of file hosting elsewhere. Primarily, this is about an August 28, 2018 promo video. The original version (seen below) urged supporters to “host the files or pay the tax for the men who will.” This video was quickly edited and re-released to remove the line.

Washington state’s lawyers did not like this at all. As they wrote:

Indeed, as discussed below, the Private Defendants appear to have an exceedingly narrow understanding of what it means to “export” the files in violation of federal law: they erroneously believe it is limited only to posting the files on their own website. Their mistaken belief underscores the need for discovery to determine whether and to what extent they may be involved in illegal and dangerous exports. Similarly, Defense Distributed may well be mailing the files to individuals who are ineligible to possess firearms, without checking their age, criminal history, or other eligibility requirements. The threat of “violations of gun control laws” if 3D-printable firearm files were to proliferate is a significant aspect of the harm to which the injunction was addressed.

(In light of that concern, it’s worth noting that, when Ars Features Editor Nathan Mattise bought a USB stick with the files from Defense Distributed, the company did not ask about his citizenship or check his age, criminal history, or any other eligibility requirements. The purchase simply required address information for billing and shipping.)

In response, Defense Distributed told the court that it shouldn’t even be part of the lawsuit. Furthermore, the company’s lawyers argued, the plaintiffs (including the state of Washington) “have no right to rifle through the Private Defendants’ papers, no right to demand disclosure of the Private Defendants’ membership lists, and no right to demand disclosure of who the Private Defendants have been talking to, who they plan to talk to, and how they carry out their constitutionally protected advocacy.”

By the end of December, federal lawyers again asked that the case be put on hold to allow the export rules to be fully changed, which “would render the current controversy moot.” But the plaintiff states requested again that the judge order compelled discovery.

Judge Lasnik has yet to rule on either the discovery question or the stay question. No further hearings have been scheduled, and there has been no more news about federal changes to the export rules. (The four-month time frame of the requested stay would approximately end in March).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1439591