If the name Hayao Miyazaki means anything to you, new documentary Never-Ending Man will, too. The film provides a pretty intimate, charming portrayal of the legendary animator from the announcement of his retirement (September 2013) through much of the production on Boro The Caterpillar, Miyazaki’s first film done entirely with CGI (that short film debuted last year).

Throughout a short hour-ish run time, this documentary maintains a very narrow focus. Never-Ending Man really only consists of footage of Miyazaki at home or at the studio, and it relies solely on interviews directly with the man or with collaborators on this project. The approach allows viewers to draw their own conclusions about why this work remains great and what makes Miyazaki tick rather than having any longtime observers or contemporaries spell such things out.

Even at this age (in his 70s), Miyazaki has an incredible dedication to detail, for instance. To make a less-than-15-minute short about a caterpillar, he’s putting insects under a microscope and working through several hand-drawn interactions before anything shows up on a computer screen. In early film footage showing pre-CGI life at Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki stands over young illustrator shoulders and offers nuanced feedback: “It’s important to draw full human beings, you’re drawing people not characters,” he tells them, soon offering slight critiques on a character’s running form or how they hold a bundled up blanket. Later when working with CGI, Miyazaki may not understand or have comfort with the tools and medium, but he continues to share similarly micro observations. “The turning motion is too adult like,” he says, watching an early render of Boro looking around his landscape. “Babies don’t turn their heads so sharply.”

Miyazaki seems to know he’s a throwback and never shies away from this—he smokes cigarettes still and insists initially on having the background landscape for Boro drawn by hand—but what makes him an all-time great is perhaps the man’s desire to make contemporary work, things that take advantage of all these new techniques and abilities, in spite of those urges. “You think CGI offers new possibilities? That’s not it,” he says when asked why bother when fans would inevitably turn out for more of his previous stuff. “I have ideas I may not be able to draw by hand, and this may be a way to do it—that’s my hope. It’s a new technology.”

This challenge clearly energized the creator. Colleagues joke Miyazaki seems to be siphoning energy from the young people around him given the age difference with all the CGI animators. Never-Ending Man director Kaku Arakawa even observed physical changes in the animator: according to the film’s linear notes, Miyazaki started drawing Boro with very soft pencils (6B) “to compensate for his weakened grip.” Over time, “as he got fired up making the CG animation and got absorbed in creating the short, he was drawing with 2B pencils again without realizing it… Mr. Miyazaki was embarrassed to admit it and exclaimed, ‘It’s not that easy to regain strength!””

-

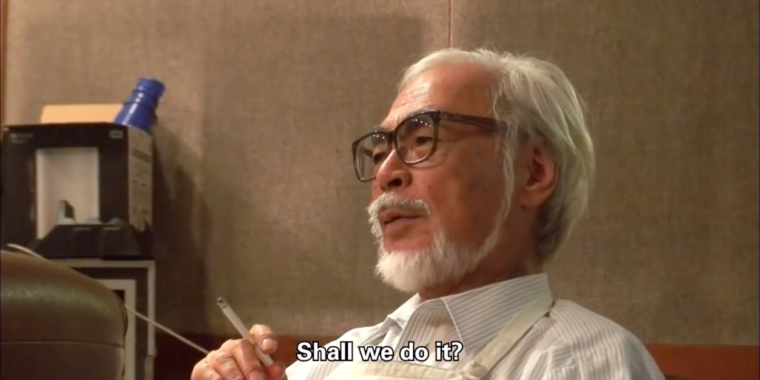

The animation legend, Hayao Miyazaki. (Spoiler: He does it.)Kaku Arakawa / GKIDS

-

Want to draw a caterpillar? Probably should observe one, first. “I can’t draw a caterpillar with a pencil,” Miyazaki says. “So i’ll turn to CGI.”Kaku Arakawa / GKIDS

-

Young Hayao Miyazaki from the new documentary, Never-Ending ManKaku Arakawa / GKIDS

-

Early proof of concepts for Boro, the subject of Miyazaki’s first CGI-animated short.Kaku Arakawa / GKIDS

-

A still from the final product

-

Miyazaki won’t be abandoning his pencil and paper anytime soon, but he willingly tinkers with Wacom tablets and similar tech.Kaku Arakawa / GKIDS

This film clearly has long-time fans in mind. Never-Ending Man doesn’t spend much time at all catching viewers up on who Hayao Miyazaki is, how he’s built his career, or what impact his films made. Such history seems contained to few short film clips and a sequence with Miyazaki flipping through old scrapbooks while acknowledging how fortunate he was in retrospect that his deeply personal ideas and tastes found larger popularity (“If we tried to please, we’d be forgotten,” he says). For someone who’s only seen a few of the big works (My Neighbor Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle), the film leaves you wanting a bit more historical and outside perspective. It’s easy to imagine a documentary that does better to contextualize the obvious legacy here in a way something like last year’s Gilbert, on raunchy comedian Gilbert Gottfried, did for watchers who know the name but not the whole story.

That said, this film still works as a small portrait of an all-time great still seeking a new challenge, a study of someone anxious to know whether the abilities and ideas that garnered such acclaim can work in what’s admittedly a new playing field. Never-Ending Man never comes out and says this, but the documentary continuously hints that technology has changed animation forever and may one day render the very thing that made Miyazaki—his unparalleled ability to translate the ideas in his head to paper through impeccable artistic skill—useless. Late in the film, for example, someone’s pitching Miyazaki on AI-enabled animation that will be able to emulate human painting within the next decade.

“We can’t stop CGI from taking over animated films,” Miyazaki says early in Never-Ending Man. He’s sketching out the lush world for Boro, coming to terms with this new reality for his beloved medium. “I did such a detailed layout not because I don’t trust them, but I want them to create something even better.”

Maybe CGI ultimately will win out—Boro debuted to much fanfare, and certainly studios like Pixar have become the premier names in animation today. But analog illustration offers something different even if the process itself isn’t as efficient, and it’s hard to imagine admiration for that ever totally evaporating. After all, while you may be able to find Never-Ending Man playing nearby, you’re perhaps even more likely to find Totoro or Howl’s Moving Castle, too.

Director Kaku Arakawa’s Never-Ending Man was made in 2016, but it didn’t receive a US theatrical release until December of last year. Screenings can still be found in select cities.

Listing image by Kaku Arakawa / GKIDS

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1446967