AUSTIN, Texas—While watching new documentary The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, I constantly marveled at the film’s effort to do the seemingly impossible: to present Elizabeth Holmes, the founder and CEO of Theranos, as a likeable person.

For one, that’s an uphill battle for a Silicon Valley burnout whose crash-and-burn reputation precedes her. For another, this documentary comes from famed takedown artist Alex Gibney, who has previously focused his filmmaking lens on the obvious-villain likes of Enron and the Church of Scientology. Shouldn’t we expect the worst?

Things get savage in The Inventor, certainly. Theranos’ worst stories have previously been laid bare, and anybody familiar with the company’s original promises—transparent, affordable bloodwork for all—won’t learn much new in this documentary. (Though, yes, The Inventor is still a fine primer for anyone going into the story blind.) Rather, what Gibney really contributes is a better look at Theranos’ secret sauce: how Holmes got so far with so little.

U can’t touch this?

-

In this interview moment, Elizabeth Holmes is asked by an interviewer to “tell us a secret.” She takes a long pause and answers, “I don’t have many secrets.” The rest of the movie suggests otherwise.

-

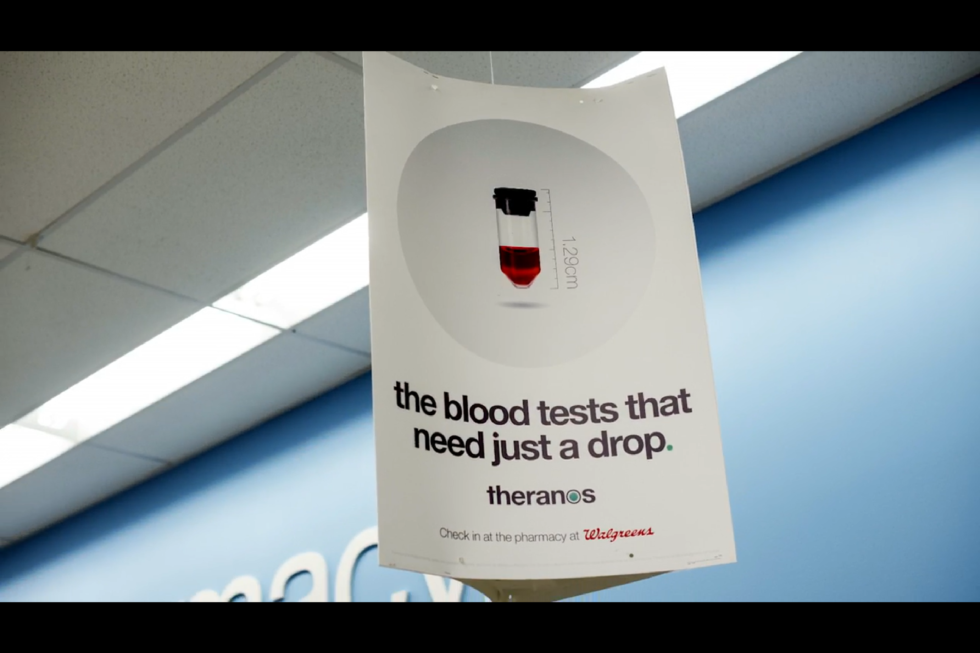

Theranos used this image on a regular basis to promote its “nanotainer” concept.

-

A photo used in the film of a younger Holmes in Theranos’ earlier days.

-

Holmes in 2015 at an all-hands company meeting, not long before a WSJ report changed everything.

-

The film explores Holmes’ obsession with Yoda.

Unsurprisingly, Holmes didn’t agree to any interviews with Gibney or his crew. Yet HBO Films still presents plenty of direct footage of Holmes talking up her former company, usually in a promotional capacity. This footage emerges with a metric ton of context, either from the journalists who profiled her or the half-dozen former Theranos employees who are now free of non-disclosure shackles.

In some cases, this means hearing stories Holmes liked to recite on a regular basis, particularly one about her beloved uncle dying at a young age thanks to undetected cancer. In others, it means getting a front-row seat to “fun” Theranos company events, like one in July 2015 that saw Holmes, fresh off some dodging-and-weaving of prying regulators and investors, dance-walk into a company party to the tune of MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This.”

But by and large, the most common version of Holmes on-screen is one of projected confidence—and selective engagement. In the film, we watch her align with countless politicians and investors while banging the drum of what might sound like a reasonable thesis. Massive blood draws, she said, are insane in a technology world where we’ve transitioned from “giant mainframes to smartphones.” And non-transparent blood-lab firms like Quest and LabCorp control 80 percent of the market using decades-old technologies.

“Change the paradigm”

“It’s time to change the paradigm,” Holmes said in response to that market reality. Her pitch was to let consumers take a much tinier draw of blood, then buy a Theranos box that would fit on a kitchen counter. The device, dubbed the Edison, could run roughly 200 tests on that sample as a solution to “the pain of traditional phlebotomy.” Users would control when and how often they got bloodwork results.

One of Holmes’ university advisers appears early in the film to talk about Holmes’ college-aged engineering idea to take advantage of microfluidics and nanotechnology and make her cutting-edge dream a reality. But that patent didn’t take medical realities into account, this source says. “There’s a reason you have a big IV bag,” Holmes’ adviser points out.

Shortly afterward, Holmes went in search of a new adviser, and she found Channing Robertson. He went on to quit his tenured Stanford job to help her start Theranos. (A 2014 Fortune feature about Holmes’ rise at Stanford only mentions Robertson, not the other advisor.)

“Blood spilled all over”

Sadly, The Inventor skimps on detailing the scientific and medical questions that fueled early doubts in Holmes’ vision, though it does make clear that Holmes, and Theranos leadership at large, sure liked to skip that part while raising money. As previously reported, Theranos consistently pushed back on any employees who expressed doubts with the vision of the Edison device, including its prohibitively small size, its unrealistic testing time window, and its high number of targeted tests.

“We couldn’t regulate the temperature,” one former employee says of a prototype Edison device late in the company’s lifecycle. “We couldn’t transfer fluids.”

In another story, an ex-Theranos employee described the company’s slapdash approach to getting sample blood: paying $100 for anonymous donors. This largely attracted a homeless population, and the company source indicated that this led to a prevalence of hepatitis in the blood. That became a concern when early Edison machines acted up.

“Blood spilled all over,” the source says. “It got gunky.” This is shown in The Inventor with a CGI illustration of how the machine might look as its automatic blood-sorting systems went awry, complete with blood caked and dried on various parts. That’s when the ex-employee explains how, when the machine would freeze or stop-and-start, “I’d have to reach in with my hand,” thus putting himself at risk to getting pricked by the Edison’s exposed needles. This also meant that blood particles, and those of potentially contagious diseases, “dissolved into the air.”

When the company wasn’t silencing its concerned employees by saying, “you don’t believe in our vision,” it was operating in highly paranoid fashion. Internal email chains may not have included Holmes or CCO (and Holmes’ boyfriend) Sunny Balwani, yet the company’s leaders would regularly reply to them. A keystroke-tracking hack was installed on at least one internal Theranos computer: the receptionist’s. (She appears in the film to ask why, incredulously.) And a “culture of silos” meant various departments were instructed not to communicate with each other.

You can lead a horse to wellness…

Any sign of doubt or disagreement clashed with the Silicon Valley archetype that Holmes obsessed over, particularly Steve Jobs. This manifested both in an it’s-impossible-until-it’s-not mantra and a love of turtlenecks. (One “iconic” photo of Holmes, holding her “nanotainer” device, looks eerily like a classic photo of Jobs holding an early iPod.)

The film takes a roundabout route to giving Holmes some semblance of dignity and integrity—by essentially saying that she ran on sheer will, fueled by a belief in intelligence and hard work being able to surmount any obstacle. In one example of how The Inventor frames her, Holmes’ ability to focus her gaze without blinking could have been used to paint her like a villain. Instead, Gibney attaches this quality to her rise as a bright new star in the health-tech sector in the early ’00s.

At that time, her sales pitch was clear: an established healthcare system had gone wrong and needed saving. She quotes Thomas Edison’s line about thousands of failures before a success, and her harshest critics in the film readily concede that when Holmes was questioned about her comfort-zone topics of engineering and future-tech visions, she was an unflappable debater and persuader.

The most striking of these defenses comes from Tyler Shultz, the lead source for The Wall Street Journal‘s 2015 exposé about Theranos’ deceptions. He admits to going back and forth between looking at hard data and serious problems while working as an engineer, then speaking directly to Holmes concerning her convictions about Edison’s development being on the right track. “You want it to be true so badly,” Shultz says. “She could still convince me.”

Early on, The Inventor reminds viewers of what a questionable and even deceitful inventor the real Thomas Edison could be, including his own overpromises about light-bulb technology before he eventually had his, er, light-bulb moment. (During this time, he bought time in the public eye by giving journalists shares of his company’s stock.) The phrase “fake it until you make it” is echoed by journalists and Theranos employees all the way through the film.

But unlike Edison and Jobs, Holmes’ path to keeping Theranos afloat eventually put real human lives on the line. In order to convince anxious investors that Edison was on the right track, the company refused to show actual footage of how the Edison machines worked. One seemingly convincing PowerPoint presentation, revealed for the first time in this documentary, was presented to Walgreens without any offer to open up an Edison box and prove its details.

Instead, Theranos worked out a deal with Walgreens to establish “wellness centers” where customers could pay for a la carte blood tests. This immediately infused Theranos with Walgreens’ cash, then attracted an additional $400 million in funding, the film reminds us.

But what was secret at the time was eventually exposed: Walgreens customers’ blood was driven away from these pharmacies, then regularly tested on competitors’ machines, which Theranos had secretly purchased. The remaining blood tests that were conducted on actual Theranos hardware were often alarmingly inaccurate.

One of the film’s most striking interviewees is a phlebotomist whose job it was to train standard Walgreens staffers with doing blood work. (“Nobody at Walgreens had handled blood!” this source points out. “What do you do if someone faints?”) This quirk of the Theranos-Walgreens relationship only got crazier when Theranos began demanding full venipuncture blood draws, which it needed to shift more of its tests to that secret stockpile of third-party blood-testing machines. Walgreens staffers were ordered not to inform customers of this bait-and-switch until moments before blood was drawn.

This phlebotomist confirms that she’d relied on Theranos’ tests for herself and her family. Once the WSJ‘s report came out, she rushed to have her entire family’s tests re-run at established firms, where she discovered she’d been lied to.

“If people are testing themselves for syphilis [using Theranos], there’s going to be a lot of undetected syphilis out there,” one former Theranos employee says in the film. And that’s nothing compared to the story of former Theranos chief scientist, Ian Gibbons, which is told in the film by his widow: “He was distraught over this stupid patent-misappropriation case [filed against Theranos]. That’s why he committed suicide.” (She then explains that she never heard from Holmes or Theranos after her husband’s death, except when they requested his confidential documents and laptop be returned.)

“Does not map to reality”

The Inventor‘s strength as a film, whether the Theranos story is old hat or brand new to viewers, comes from its breadth of sources eager to clear their names. Fortune writer Roger Parloff is the most visceral of these, having profiled Holmes for a major cover story in 2014, and by the film’s end, we watch him swallow his anger and curse Holmes’ name. “What comes out of her mouth does not map to reality as you and I know it,” Parloff says.

We also see at length the crazy, winding road that Theranos went down with that aforementioned WSJ source, Tyler Shultz, whose grandfather happens to be former Secretary of State George Shultz—a major Theranos investor and self-proclaimed adoptive grandfather of Holmes. (Tyler’s work at Theranos began in part because of how often Holmes would attend Shultz family gatherings, where she charmed Tyler into wanting to be a part of Theranos’ future.)

After the WSJ‘s report was published, Theranos figured out that Shultz was one of its sources… by combing staffers’ emails until finding a “42.7 percent” notation, which the WSJ had included in its article. Theranos began sending threatening letters to Shultz, which cost him and his parents roughly $500,000 in legal fees to deal with.

This legal battle ended in a sting operation that took advantage of Holmes’ association with the Shultz family: two Theranos lawyers were waiting for Tyler when he went to his grandfather’s house.

The resulting confrontation is described at length by George Shultz in a hearing that led to charges filed against Holmes and Balwani. His patience with Theranos ran out once he watched its lawyers “assault” his grandson, he testified.

Yet in that same hearing, the elder Shultz insisted that he believed and still believes that Holmes acted with the utmost of honesty and integrity as CEO and founder of Theranos. And The Inventor leaves enough breadcrumbs between its stories of blind ambition and dangerous, careless policies to show how Holmes swept everyone up—Joe Biden, Bill Clinton, Henry Kissinger, former US Defense Secretary James Mattis, and scores of excited, budding entrepreneurs, particularly women—with her determination to reinvent medical access.

“She was a good idol to have,” one ex-Theranos employee and Holmes admirer says in the film. “I drank the Kool-Aid too quickly.”

The Inventor: Out For Blood in Silicon Valley had its final preview screening at SXSW 2019, ahead of its cable television premiere Monday, March 18, on HBO.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1473801