As Kabul fell on Sunday, 20 young Afghan tech workers tracked the Taliban’s advance, broadcasting real-time reports of gunfire, explosions, and traffic jams across the city through a new app.

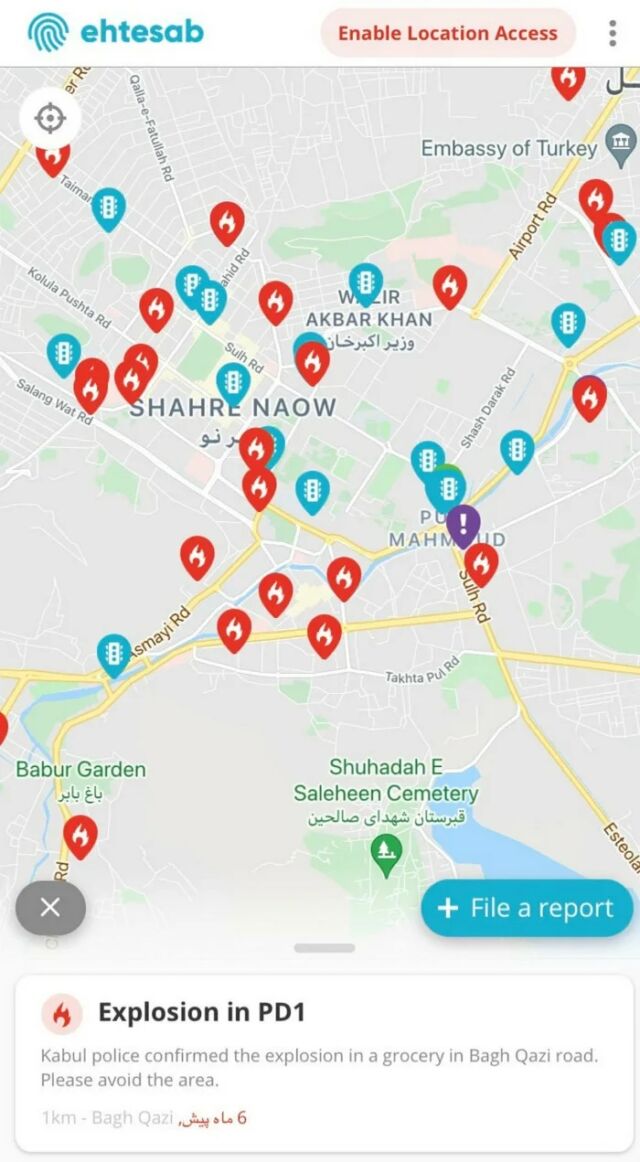

Called Ehtesab, the app relies on ground-level reports from a vetted team of users to a private WhatsApp group.

The reports, which are then verified by the app’s fact checkers, range from security incidents, such as fires, gunshots and bombings, to road closures and traffic problems to electricity cuts. Sara Wahedi, the 26-year-old founder of the app, said the team tried to confirm the reports with the interior ministry, “when it used to exist.”

On Sunday morning, Wahedi and her team were supposed to be uploading the new version of their iOS app but instead found themselves dealing with an ever more frantic stream of reports.

“Breaking on the @ehtesabaf App: Taliban have entered Arghandi, Paghman District. South Gate of Kabul. ANDSF [Afghan National Defence and Security Forces] under attack,” Wahedi wrote on Twitter at the time.

She said that as the Taliban advanced across Afghanistan, Ehtesab had built a reliable way of “getting reports from a lot of different security structures,” including police, the government and international organisations.

Soon the team started receiving reports that the Taliban had captured Bagram prison, in the former US military base just north of Kabul.

“At that point our reporting mechanisms were still in place, so it was easy to converse with our security team and all our reporters. We were monitoring minute by minute, talking to different police districts, tracking the Taliban kilometer by kilometer by that point,” she said.

“But by the time they reached the city center, everything shut down, nothing was online, there was no way of speaking to each other. People deleted their messages or turned off their phones. When the Taliban reached the president’s office, it was like, ‘OK, now we have to work alone’.”

Ehtesab, which means “accountability” in Pashto and Dari, is co-owned by Afghan company Netlinks, which invested $40,000, and Wahedi, who said she has put in $2,500 of her own money.

“I didn’t want to register as an NGO, to be benchmarked or limited by the United Nations or the United States. This is an Afghan-led and funded, fully 100 percent Afghan team working on this,” she said.

Users of the app can opt to receive phone alerts based on their location, warning them to avoid certain areas, buildings or businesses. They can also report incidents themselves via the app, which turns on your camera and microphone so you can send video footage to Wahedi’s team. The goal, she said, is to empower local communities with live information on which to act.

Ehtesab is still running, and Wahedi said she wants to keep operating it as long as possible, although she is currently outside Afghanistan. She has managed to raise nearly $15,000 through a GoFundMe campaign, part of which she will send to her team in Kabul as emergency funds.

Her plan is to build a nationwide alert system, not just through the apps but through SMS warnings as well. Their office in central Kabul remains closed, with employees working from home, but they plan to upload a new iOS version as soon as they can get back to their desks.

“We just want to alleviate some of the anxieties that Afghans have in these uncertain and volatile times,” she said. “We will find different ways of garnering data about the city and security… That’s the beauty of tech, it knows no borders,” she said.

Wahedi founded the company in 2018, after spending two years working for President Ashraf Ghani’s office on Afghanistan’s social development policy, but insists she is not affiliated to any political group.

She had moved back to her hometown as a 21-year-old, after having escaped Taliban rule in her native Kabul to go to Canada as a refugee at the age of six. Two decades later, the Afghan entrepreneur found herself fleeing from the Taliban again. This time she does not know if she will ever be able to return. “It’s like Groundhog Day,” she said.

Today, she is using what she calls the “privilege” of having escaped Kabul to try to put her friends and family on charter flights out of Afghanistan.

“I’m grateful to be with my mom but the guilt is crippling when I think about my home, when I think about the fact I’ll never be able to go back to the Kabul I’ve known for so long,” she said. “I don’t think any of us will ever be the same again.”

© 2021 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1789110