This weekend, I was excited to deploy my first Ryzen 3000-powered workstation in my home office. Unfortunately, a microcode bug—originally discovered in July but still floating around in large numbers in the wild—wrecked my good time. I eventually got my Ryzen 3700X system working, and it’s definitely fast. But unfortunately, it’s still bugged, and there’s no easy way to fix it.

Not long after the product launch, AMD Ryzen 3000 customers started noticing problems with their shiny new CPUs. Windows users couldn’t successfully launch Destiny 2 (due to a power-management bug, unrelated to the one sidelining my system), and Linux users in many cases couldn’t even get their system to boot. Jason Evangelho covered the initial discovery and report of the bug at Forbes back in July, and an AMD representative provided him with a statement by email:

AMD has identified the root cause and implemented a BIOS fix for an issue impacting the ability to run certain Linux distributions and Destiny 2 on Ryzen 3000 processors. We have distributed an updated BIOS to our motherboard partners, and we expect consumers to have access to the new BIOS over the coming days.

This sounds happy and upbeat, but the reality isn’t quite so simple. When there’s a bug in the CPU microcode, you’re at the mercy of your motherboard vendor to release a new system BIOS that will update it for you—you can’t just go to some download link at AMD and apply a fix yourself.

AMD responded to the bug in July. As far as I can tell, AMD did so only by direct email response; there’s no press release about it—and the company’s response made it sound like everything would be fixed in a week or two.

I have the unfortunate duty of reporting to you, three months later, that it is not.

What’s an RDRAND?

The microcode bug in question is a faulty response to the RDRAND instruction. Modern x86_64 CPUs—beginning with Intel’s Broadwell and AMD’s Zen architectures—are supposed to have high-quality onboard random number generators (RNGs), which use thermal “noise” to very rapidly offer high-entropy pseudorandom numbers to anybody with kernel-level access who wants it. RDRAND is, in turn, the instruction that provides these random numbers.

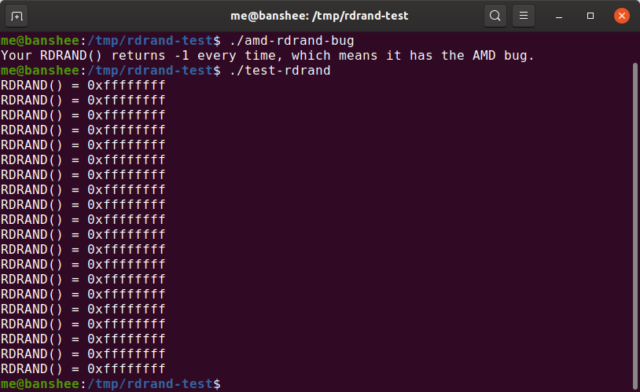

All of this is supposed to be fairly failsafe. There’s a CPUID function call that checks for the availability of RDRAND, and there’s also a “carry bit” in the return value from a call to RDRAND that’s supposed to let the calling application know if the CPU’s RNG was unable to generate a sufficiently random number due to lack of entropy. Unfortunately, unpatched Ryzen 3000 says “yes” to the CPUID 01H call, sets the carry bit indicating it has successfully created the most artisanal, organic high-quality random number possible… and gives you a 0xFFFFFFFF for the “random” number, every single time.

-

In a sufficiently broad dataset, 20 consecutive 0xFFFFFFFF returns might be considered a valid “random” grouping. This is not a sufficiently broad dataset.Jim Salter

-

You shouldn’t rely on /dev/hwrng to tell you if you’re NOT vulnerable to the AMD microcode bug, because /dev/hwrng might be getting its data from somewhere else. In my case, it’s getting its data from RDRAND, and it’s pretty obvious that data’s no good.Jim Salter

Obvious RDRAND bug impacts

When theRDRAND bug in Ryzen 3000 first surfaced back in June, Linux users widely reported that their entire Ryzen 3000-powered systems wouldn’t boot. The failure to boot was due to systemd’s use of RDRAND—and it wasn’t systemd’s first clash with AMD and a buggy random-number generator, unfortunately.

A much earlier bug in older CPUs caused some AMD systems to stop generating properly “random” numbers after resuming from suspend. The new bug caused Ryzen 3000 users to never get any proper random numbers at all. Both problems caused lockups in Linux operating systems using systemd, so in May systemd committed a patch that falls back to using alternate RNG sources if systemd receives the characteristic 0xFFFFFFFF back from the RNG. (This kinda sucks, because 0xFFFFFFFF is technically a perfectly valid random number—the implication here is that, after a sufficient length of time, systemd will decide any system has a buggy RNG when it eventually receives the “bad” number, even if it has never seen that number before.)

Systemd’s patch is ugly, but it certainly works well enough to allow systems to boot. Unfortunately, it doesn’t fix the actual problem, which is that the CPU’s random number generator is no more “random” than a two-headed penny. On my own system, I spent my entire weekend chasing phantom problems, first suspecting the system’s brand-new RX 590 graphics card and (necessarily) updating distro and kernel versions before haring off from there.

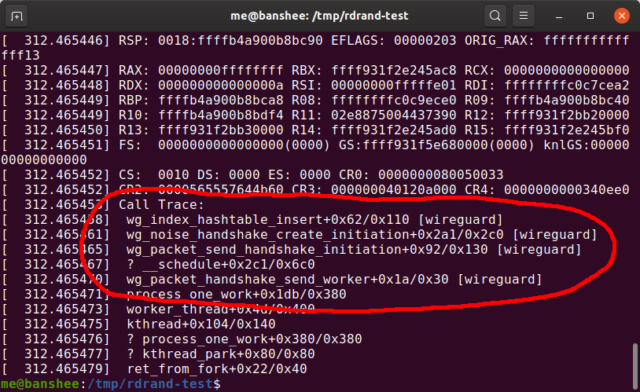

—PU#n stuck for 22s errors, which would rapidly lock the whole system up. This call trace from /var/log/syslog didn’t tell me the actual problem, but it was the first clue.

Eventually, after many false trails and much swearing, coffee, and less-respectable beverages, I actually read the call trace from my frequent CPU lockups—and “WireGuard” was right there, in every one of them. As it turns out, WireGuard relies on RDRAND (when available) to generate new session IDs. The session IDs need to be unique, and WireGuard wants them not to be simple consecutive integers, so it pulls a pseudorandom value from RDRAND, compares it against its existing session ID list to make sure there’s no collision, then assigns it to the session.

Read that last part again carefully—it makes sure there’s no collision first. If an existing session has the same ID as the new number, WireGuard asks RDRAND for another “random” number, checks it for uniqueness, and so on. Since RDRAND on my system—and any non-microcode-updated Ryzen 3000 system—always returned 0xFFFFFFFF no matter what, that means infinite loop. Infinite loops in kernel code are bad; they introduce you to the value of the hardware reset button in a hurry.

I want to be very clear here, this is not a WireGuard bug! WireGuard correctly checks to see if RDRAND is available, fetches a value if it is, and correctly checks to see if the carry bit is set. Then it indicates that, not only is there a value, it’s a properly random one. Nevertheless, it’s one that will lock up affected systems hard. So after considerable discussion this morning, the project decided it will implement a simple detection-and-fallback routine.

The fallback routine will allow WireGuard—and systems with WireGuard installed—to work even in the presence of the bug. But it still doesn’t fix the problem. A modern system needs high-quality pseudo-random numbers for lots of tasks, and the security implications of “random” meaning “always return0xFFFFFFFF” are difficult to predict. One obvious candidate is Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR). Both Windows and Linux use RDRAND as at least part of the randomness used to make sure code is never loaded in the same order twice, which mitigates against stack-smashing attacks.

Fixing the problem—or at least recognizing it

As AMD’s representatives told reporters back in July, the real fix comes from applying BIOS updates to your motherboard and hoping that the BIOS update also includes the microcode patch for the CPU itself. When I checked my own BIOS using the dmidecode utility, I saw a date of August 12, 2019. But when I looked at Asus’ download page for my motherboard, I saw downloads dated in September! Hurray! So I downloaded the BIOS update, saved it to a FAT32 thumb drive, rebooted my system, and went into setup.

Unfortunately, after successfully applying the update and rebooting again, I realized my error—yes, Asus showed a later date for the BIOS, but the actual version was the same as the one I already had—3.2.0. My CPU still thought 0xFFFFFFFF was the randomest number ever, always, no matter what.

At this point, I began to get paranoid—systemd had already quietly worked around the bug, and WireGuard was (thankfully) about to do the same. But with most applications just quietly ignoring the problem, how would I know if it ever had been patched? What if two years later, I was still vulnerable to stack-smashing that I shouldn’t have been, due to ASLR that wasn’t actually randomizing?

I discovered that I could use the linux utility hexdump against the kernel device /dev/hwrng to demonstrate that I had the problem. Unfortunately, the WireGuard project’s Jason Donenfeld warned me that /dev/hwrng could, on some systems, derive its randomness from other sources—so while seeing a bunch of FF from it demonstrates that you have the problem, seeing valid pseudorandom data doesn’t necessarily demonstrate that you don’t. So he generously whipped up a couple of test utilities for the purpose that safely access RDRAND directly.

If you’re a Linux user, you can download rdrand-test.zip, unzip it, and run it directly in the folder that you unzipped it in. ./amd-rdrandbug will tell you in plain English whether you have this specific bug, and ./test-rdrand will output a 20 test RDRAND fetches. So you can confirm for yourself that you’re not vulnerable to similar bugs either—if running ./test-rdrand produces the same set of values every time, it doesn’t really matter whether they “look random,” your RNG is broken!

If you’re a Windows user, you have a little more work ahead of you. First, download an Ubuntu desktop installer, then create an Ubuntu installer thumb drive. Then you can boot into the Ubuntu thumb drive’s live environment (click “Try Ubuntu”) and download and run the tests from there:

you@ubuntu-live:~$ wget https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/rdrand-test.zip you@ubuntu-live:~$ unzip rdrand-test.zip you@ubuntu-live:~$ cd rdrand-test you@ubuntu-live:~$ ./amd-rdrand.bug

Conclusions

A broken random-number generator is a very serious bug, and it’s troubling that more hasn’t been said or done about this issue by AMD in the last three months. Ryzen 3000 is a great CPU platform in general, and I’ve been very impressed with the new system… except for spending an entire frustrated weekend troubleshooting it, being uneasy about the impact this will have on my overall system security, and having no idea when I can expect to be able to actually fix it.

I reached out to AMD representatives earlier today, and they’ve responded with questions about my hardware but no solutions yet. I’ll update this article with any fixes or recommendations as they arrive.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1592361