Indiana Jones is caught behind the Iron Curtain. Specifically, the globe-trotting archeologist is in the former Czechoslovakia, a Soviet satellite state, and he’s fighting violent Communists, dodging water cannons, balancing on the edge of a crater, and running away from exploding bombs—the usual Indiana Jones stuff. But there’s no artifact this time. Instead, like many of the citizens toiling under the discredited regime, Dr. Jones simply wants to escape Czechoslovakia and return to the United States.

If you’re familiar with the Indiana Jones tetralogy trilogy, you know the situation above doesn’t come from the movie canon. Instead, this Jones adventure takes place in a clandestine video game that was released anonymously, then copied from one audio cassette to another. In 1989, students and dissidents had flocked to the center of Prague to protest Communism, only to be beaten and arrested by the riot police—an incident that took place during the lead up to the country’s historic Velvet Revolution. These individuals could not fight back in real life, so they’d later use their computers to get a fictional revenge. A Western hero, Indiana Jones, came to their rescue to teach their oppressors a text-based lesson.

The Adventures of Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square in Prague on January 16, 1989 puts the famous archeologist when and where the protests took place, video game historian Jaroslav Švelch, assistant professor at Charles University in Prague, Czechia, tells me. This title and others created by Czechoslovak teenagers in the late 1980s became part of the “chorus of activist media” that included student papers, rock songs, and samizdat—handwritten or typewritten versions of banned books and publications that circulated illegally.

This Indiana Jones game, however, stands apart as a cultural curiosity. And Švelch, a zealous academic interested in the social aspects of gaming, has recently translated it into English. After 30 years, people from all over the world could finally play and learn about this unique moment of early activism in video game history.

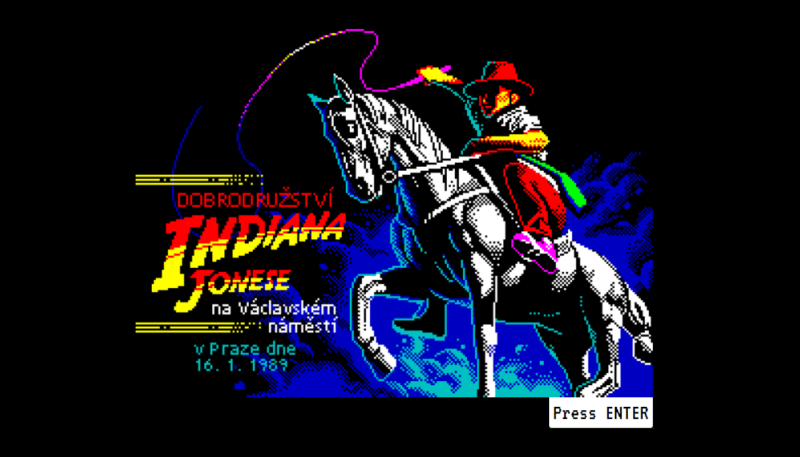

This year, Švelch worked with a fellow 8-bit veteran, programmer Martin Kouba, to bring Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square to life again in 2020. The original foreign-language version was a typical 1980s text-adventure that only had words, no drawings. Švelch and Kouba wanted to immerse today’s young players into the universe of the 1980s, so they accurately converted the game, only adding a colorful opening screen featuring the fedora-toting archeologist. The result awaits eager players right now in a simple Web browser.

If translating a decades-old text-based adventure then converting it into a playable browser game sounds complicated, the story of how this game (and its 1980s Czechoslovak text-adventure peers) came to exist may seem as improbable as finding The Ark of the Covenant.

How Indiana Jones fascinated the Czechoslovaks

Czech and Slovak teenagers first heard about Indiana Jones in July 1985, when Raiders of the Lost Ark premiered in local cinemas four years after its official release in the US. František Fuka, a 16-year-old boy sporting a Beatles haircut, loved American movies. Capitalist productions were only shown a few times a year amid the glut of Soviet and local titles, and for the high schooler, they were a breath of fresh air.

“I wanted to see them all,” he tells me.

Before the premiere, he knew nothing about Indiana Jones, but the professor with a bullwhip quickly made an impression. Regardless of how terrifying a situation could be, Indy was in control of it. His wit and the fast pace of his actions while trying to retrieve the Ark of the Covenant were astonishing. None of the Soviet Bloc productions Fuka previously saw could match Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. To him, Indiana Jones, portrayed by Harrison Ford, was more than a hero. He was an exponent of the promised land: the West.

“I was blown away,” he says.

By that time, Fuka already had four years of coding experience. He learned BASIC with his friends at the Union for Cooperation with the Army (Svazarm). Officially, this was a paramilitary organization tasked with training young people for potential roles in the military, but it acted more as a Boy Scouts club that gathered kids interested in motorsports, ham radio, model planes, electronics, and computers.

There, Fuka learned that building video games was cooler than just playing them. So as soon as he left that movie theater in Prague, dazzled by the stunts and the theatrics of Indy’s battle with the Nazis, he knew he had to create an adventure around this hero. Copyright and intellectual property were elusive concepts in the Eastern Bloc, so the teenager saw no problem in designing something that would fall into the fan fiction category.

Fuka knew many young people in his country had seen or would watch Raiders of the Lost Ark, so retelling the story would be redundant. He decided instead to focus on the second movie of the franchise, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The film had been released in the West, but nobody knew when it would reach Czechoslovakia.

In the movie, Harrison Ford’s hero goes to India to chase a mystical stone, smash a death cult, and bust a child slavery ring. But Fuka couldn’t watch the movie, so instead he looked for clues about the plot in magazines.

“I read very short summaries,” he tells me. “I mixed what I thought the second movie was about with elements from the first. I got it completely wrong!” (Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom would only be released in Czechoslovakia a year later, in 1986.)

The game the teenager built was rather simple. Its opening screen featured an attempted drawing of Indiana Jones, a snake, a spider, and the Fuxoft logo (a name that combined his name “Fuka” and “soft” for software). With the exception of that loading screen, everything is text. Players see sentences that tell a story, and they have to type commands, instructing the hero in what to do. It’s a typical text-adventure, known locally in Czechoslovakia as textovka, and it unfolds just like an interactive story.

In this game, Indy finds himself in the Amazon rainforest, in front of a large underground complex called the Temple of Doom. He has to retrieve the golden mask of the God of Sun while shaking off his pet hate—venomous snakes. The player types predefined commands such as “take box” or “jump truck” to guide the hero.

Fuka began designing the game with pen and paper, drawing a map of all the locations the character would go through. Then, he wrote the code in BASIC on a British Sinclair ZX Spectrum, a small 8-bit personal computer that connects to a TV set, which it uses as a screen. The PC has a rainbow band on the right and gray rubber keys with BASIC commands written on them. For instance, pressing “W” would insert the command “DRAW.” The ZX Spectrum was fairly affordable for a computer in the 1980s, which made it immensely popular in the UK and throughout Western Europe, where it was seen as a rival to the American Commodore 64.

But behind the Iron Curtain, in Czechoslovakia, owning a Speccy or even a local clone intended for schools, known as the Didaktik, was challenging. These computers were seldom sold in stores; Fuka and most of his mates instead acquired them from the West. Fuka recalls that his friend’s parents smuggled the teenager’s Spectrum into the country inside a diplomatic suitcase to avoid border control. Others might cloak their PCs in chocolate boxes or wrap them in sandwich paper and conceal them in the trunk of their Trabant or Skoda cars while entering the country.

“I put my real phone number in the game and I got a lot of calls from totally unknown people who wanted to know how to finish specific puzzles, because it was an unforgiving adventure,” he tells me.

This also meant his mother had to field calls from anguished players, unable to save Dr. Jones and needing tips. But she was openminded and even enjoyed talking to her son’s fans.

“Next to the phone, I had some basic questions and answers prepared on paper,” Fuka says. “So when I wasn’t at home, my mother could answer for me.”

Shortly, the teenager established his reputation as a leading game developer in Czechoslovakia, and he capitalized on that years later. He wrote two more Indiana Jones text-adventures and several others, he authored books, became a movie reviewer, and even dubbed American movies smuggled into the country, which people clandestinely watched at home on VCRs.

Fuka was “in a unique position to become a trendsetter for the community,” computer games historian Jaroslav Švelch writes in his award-winning book, Gaming the Iron Curtain. The teen’s uncle fled Czechoslovakia in the late 1970s for the US and subscribed his nephew to American and British computer magazines such as Creative Computing and Your Sinclair.

“I learned a lot of English just by constantly reading them again and again, even if I didn’t understand them at first,” Fuka tells me.

His work inspired other teens to write text-adventures and, by the late 1980s, more than half of local games were part of this genre. As for Indiana Jones titles, there were at least seven of them, all unlicensed, including one featuring a so-called “Indiana Joe.”

I asked Fuka if he knows who the author of the subversive Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square might be. He tells me he has no clue.

“It’s not me,” he adds.

This activist title is credited to a Zuzan Znovuzrozený, which translates to “Susan Reborn.” The address listed is Zero Unpleasant Street, Zilch City, Nowhereland. Švelch suspects that the author was probably afraid of repercussions, and that’s why they remained anonymous. It was probably someone who had a personal stake in the actual demonstration in January 1989. Maybe they were beaten by the police, or they had to escape Wenceslas Square and run away, just like Indiana Jones in the game.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1716215