Last week, researchers published the results of a clinical trial that used CRISPR gene editing to create a large population of cancer-targeting immune cells. The trial was short, and the reprogrammed immune cells weren’t especially effective against the cancer. But the technology, or something similar, is likely to be used in additional attempts to attack cancer and potentially treat a variety of diseases.

So, the trial provides a good opportunity to go through and explain what was done and why. But if you go back and re-read the first sentence, a lot was going on here, so there’s a fair amount to explain.

Cancer and the immune system

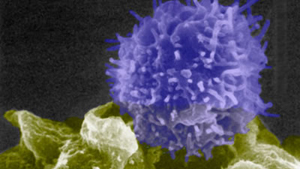

Cancers and the immune system have a complicated relationship. The immune system apparently eliminates many cancers before they become problems—people who are on immunosuppressive drugs experience a higher incidence of cancer because this function is inhibited. And, even once tumors become established, there’s often an immune response to the cancer. It’s just that cancer cells evolve the ability to evade and/or tamp down the immune response, allowing them to keep growing despite the immune system’s vigilance.

There are two major ways that these interactions have been targeted by cancer therapies. One approach, which won the Medicine Nobel in 2018, involves inhibiting the proteins that allow tumors to tell the immune system to back off. These drugs restore the immune attack and can help eliminate some types of cancer.

That same Nobel also honored the alternate means of revving up the immune response: providing an influx of tumor-attacking immune cells. The approach, generically termed CAR-T therapy, involves taking immune cells from the patient, reprogramming them to attack a tumor, growing up large numbers of the reprogrammed cells in culture, and finally putting them back into the patient. The approach has seen some success in clinical trials, and commercialized versions of CAR-T therapy have been approved by the FDA.

The key to reprogramming T cells to attack cancers involves hijacking the system these immune cells normally use to attack infected or foreign cells. T cells produce a complex of proteins called the T Cell Receptor (TCR) that recognizes when other cells are making unusual proteins due to the presence of a pathogen or mutations. The TCR has two parts: a constant portion that’s identical in all T cells and links them to signaling networks within the cell; and a variable area that’s different in different cells and helps recognize unusual proteins.

So, when the variable portion of a TCR recognizes an unusual protein, it sets off the T cell’s signaling networks, triggering responses that can include killing the cell.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1897734