“You just have to believe!” is the kind of trite line you’d expect in a kids’ movie about a magic talking dog. But it seems the phrase doubles as important advice for college professors. That’s the upshot of a huge study at Indiana University, led by Elizabeth Canning, where researchers measured the attitudes of instructors and the grades their students earned in classes.

Mind the gap

One of the disappointing problems in higher education is the frequent existence of an “achievement gap” between underrepresented minorities and other students. It seems to be the result of various obstacles that students face along the way, from stereotypes about which groups are naturally skilled in which fields, to cultural differences that make some students hesitant to seek help in a class, to a lack of advantages in primary and secondary education. A lot of things can get in the way.

So these scenarios don’t have to take the ugly form of a racist teacher outright telling a student they aren’t welcome. Many issues are unintentional and subtle. If a student has the perception, for any reason, that they aren’t expected to succeed, that can drain enough motivation to ensure that they don’t.

This is why the researchers decided to look at something subtle that they expected might be important: whether professors felt that a student’s intelligence is fixed and unchanging or whether they thought it could be developed. A simple survey was sent out to all the instructors of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) courses at Indiana University, and an impressive 40 percent responded—150 instructors covering 634 courses. The researchers also gathered other details, like years of experience and ethnicity.

Next, the researchers were given access to two years’ worth of students’ grades in those instructors’ classes, covering a total of 15,000 students. Identifying information was removed, but some information, like entering SAT scores and ethnicity, was retained. In an extra step, the researchers also got the feedback evaluations submitted by students, although these responses were fully anonymous.

Fixed or flexible

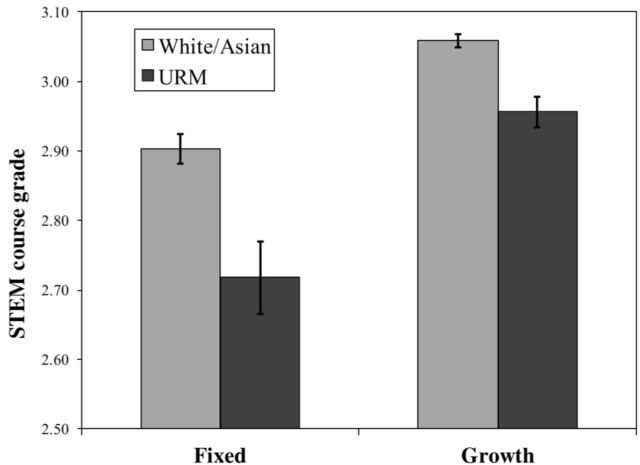

The results showed a surprising difference between the professors who agreed that intelligence is fixed and those who disagreed (referred to as “fixed mindset” and “growth mindset” professors). In classes taught by fixed mindset instructors, Latino, African-American, and Native American students averaged grades 0.19 grade points (out of four) lower than white and Asian-American students. But in classes taught by “growth mindset” instructors, the gap dropped to just 0.10 grade points.

No other factor the researchers analyzed showed a statistically significant difference among classes—not the instructors’ experience, tenure status, gender, specific department, or even ethnicity. Yet their belief about whether a students’ intelligence is fixed seems to have had a sizable effect.

The students’ course evaluations contain possible clues. Students reported less “motivation to do their best work” in the classes taught by fixed mindset professors, and they also gave lower ratings for a question about whether their professor “emphasize[d] learning and development.” Students were less likely to say they’d recommend the professor to others, as well.

Is it possible that the fixed mindset professors just happen to teach the hardest classes? The student evaluations also include a question about how much time the course required—the average answer was slightly higher for fixed mindset professors, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Instead, the researchers think the data suggests that—in any number of small ways—instructors who think their students’ intelligence is fixed don’t keep their students as motivated, and perhaps don’t focus as much on teaching techniques that can encourage growth. And while this affects all students, it seems to have an extra impact on underrepresented minority students.

The good news, the researchers say, is that instructors can be persuaded to adopt more of a growth mindset in their teaching through a little education of their own. That small attitude adjustment could make them a more effective teacher, to the significant benefit of a large number of students.

Open Access at Science Advances, 2019. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aau4734 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1457477