About 120,000 years ago, two or three people walked along the shore of a shallow lake in what is now northern Saudi Arabia. They left behind at least seven footprints in the mud, and today those tracks are the oldest known evidence of our species’ presence in Arabia.

A Pleistocene walk by the lake

Imagine that you’re a hunter-gatherer about 120,000 years ago, and you’re walking out of eastern Africa into Eurasia. Paleoanthropologists are still debating exactly why you’ve decided to do such a thing, and you almost certainly don’t have a destination in mind, but for now we’ll take it for granted that you just want to take a really, really long walk. Almost inevitably, you’ll come to the Levant, on the eastern end of the Mediterranean. From that important geographical crossroads, you’ve got some options: you could head north through Syria and Turkey, then veer east into Asia or west into Europe. You could also strike out east, across the northern end of the Arabian Peninsula.

That was a better option then than it sounds now. Off and on during the Pleistocene, the Arabian Peninsula had a wetter climate than it does today. Evidence from ancient sediments, pollen, and animal fossils all suggest that today’s deserts were once grasslands and woods, crossed by rivers and dotted with lakes like the one at Alathar in the western Nefud Desert.

As a result, the Arabian Peninsula has been an important route for hominins’ expansion beyond Africa, which started with Homo erectus and eventually ended with Homo sapiens. 300,000-year-old stone tools at one site in the Nefud probably mark the presence of an early wave of hominins, probably Homo erectus. And last year, archaeologists found an 85,000-year-old fossil finger bone in the Nefud—the oldest directly dated Homo sapiens fossil anywhere outside Africa or the Levant. The footprints at Alathar suggest that our species had reached Arabia even earlier.

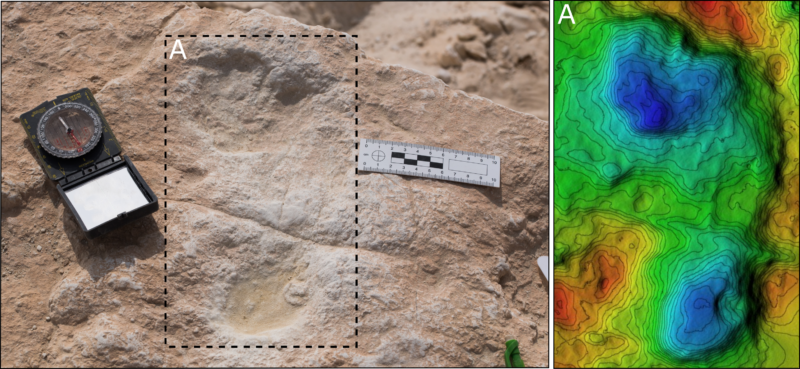

How can we be sure? Neanderthals had wider, heavier feet with shallower arches compared to most Homo sapiens, and the proportions of the prints at Alathar look more like Homo sapiens feet. There’s also no trace of anyone else in the region at that time (so far), so our species looks more likely. And based on the different sizes of the tracks, the group probably included at least two or three people.

Using a method called optically stimulated luminescence, paleoecologist Mathew Stewart of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology and his colleagues dated the layer of sediment just above the layer with the footprints, as well as the layer just below them. Over tens of thousands of years or more, quartz grains trap electrons in their crystal structure (the electrons end up trapped because natural radiation excites them into bouncing around until they get stuck). When scientists come along and zap a sediment sample with light, those electrons get released, giving off photons in the process. By measuring the photons, scientists can tell how long ago a rock or layer of sediment last saw the light of day. That provided a handy set of brackets on the possible age of the footprints: somewhere between 112,000 and 121,000 years old.

Just passing through

Back then, Alathar was a shallow lake in a low spot between dunes. The silica fossils of single-celled algae in the footprint layer suggest that when the small group of people visited, the lake was in the process of drying up as the climate shifted. But it still held enough freshwater to offer an appealing stop in the arid landscape for humans and for a menagerie of other Pleistocene wildlife.

The ground around the lake deposit is “heavily trampled,” with at least 376 tracks from various animals. Many of the tracks had been muddled by erosion and trampling, but the 177 that Stewart and his colleagues could identify provided a snapshot of the ecosystems early humans were part of as they expanded into southwest Asia.

At Alathar, people crossed paths with whole herds of elephants and camels, along with at least one giant buffalo and a wild ass. It’s likely that all of those animals visited Alathar within days or even hours of each other, because footprints in mud tend to fade away quickly unless they’re preserved somehow. (If you’re an ichnology enthusiast, it’s worth noting that experiments in a mudflat show that human footprints lose their fine details within about two days and become totally unrecognizable in four.)

“Movement and landscape use by humans and mammals in Arabia were inextricably linked,” wrote Stewart and his colleagues.

Although both people and animals walked in all directions at Alathar—along the shore, to and from the lake, and on other paths—the tracks all eventually make their way from north to south. Stewart and his colleagues suggest that the large herbivores like elephants, camel, and buffalo could have been moving south to follow a seasonal shift in rainfall. Modern elephants in east Africa do the same thing today, and they follow chains of lakes like the chain Alathar was a part of 120,000 years ago.

The small group of people who passed by the lake at Alathar may have been following the water, the herds, or both, but they didn’t stay long, in any case. There’s no trace of stone tools, animal butchery, hearth fires, or anything else that would indicate people actually lived and worked here. At other ancient lakes in the Nefud, archaeologists have found stone tools and other evidence that people stuck around for a while, but not at Alathar.

“It appears that Alathar Lake was only briefly visited by humans,” wrote Stewart and his colleagues. “It may have served as a stopping point and a place to drink and forage during long-distance travel, perhaps initiated by the arrival of dry conditions and dwindling water resources.”

Science Advances, 2020 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aba8940 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1707697