The year is 150 CE. It’s a humid summer day in Muyil, a coastal Mayan settlement nestled in a lush wetland on the Yucatan Peninsula. A salty breeze blows in from the gulf, rippling the turquoise surface of a nearby lagoon. Soon, the sky darkens. Rain churns the water, turning it dark and murky with stirred-up sediment. When the hurricane hits, it strips leaves off the mangroves lining the lagoon’s sandy banks. Beneath the tumultuous waves, some drift gently downward into the belly of the sinkhole at its center.

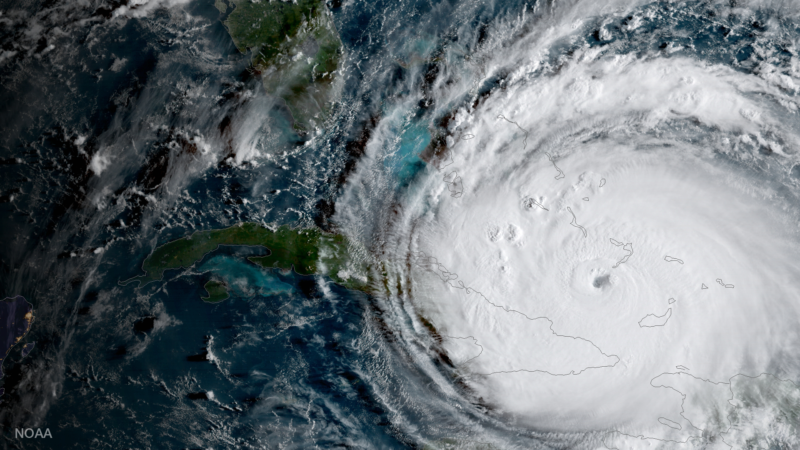

Nearly two millennia later, a team of paleoclimatologists have used sediment cores taken from Laguna Muyil’s sinkhole to reconstruct a 2,000-year record of hurricanes that have passed within 30 kilometers of the site. Richard Sullivan of Texas A&M presented the team’s preliminary findings this month at AGU’s Fall Meeting. The reconstruction shows a clear link between warmer periods and an increased frequency of intense hurricanes.

This long-term record can help us better understand how hurricanes affected the civilization that occupied the Yucatan Peninsula for thousands of years. It also provides important information to researchers hoping to understand how hurricanes react to long-term climate trends in light of today’s changing climate.

Sinkholes are ideal record-keepers

Today, the Muyil Ruins still peek over the trees at Laguna Muyil, which is located within the Sian Ka’an Bioreserve in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Sullivan’s team retrieved two 40-feet-long sediment cores from the bottom of a 60-feet-deep sinkhole on the southern end of the lagoon. The cores were collected using a floating raft equipped with a vibrating tube that dug into the sediment.

After collection, the team compared the top layers of the cores to the 150-year instrumental record maintained by NOAA to understand how close and intense a hurricane needed to be to show up as a band in their samples. Sullivan’s team found that Category 3 and higher hurricanes that passed within 30 kilometers of the site leave a clear visual record as layers of coarse sediment.

“When a storm comes through, that high-energy system is going to mobilize denser and heavier particles and transport them into these holes,” Sullivan said. “Looking for those transitions between coarse-grained and fine-grained material is how we start to detangle this record of environmental change.”

The next step was to radiocarbon date the layers using leaves, sticks, and seeds that were blown into the hole. The more organic debris present, the more confident the researchers could be about the precise timing of intense hurricane activity. In the Muyil cores, each centimeter of sediment roughly corresponded to 1.5 years, providing a high-resolution record extending back nearly 2,000 years.

The benefit of the long view

Since instrumental hurricane records only go back 150 years, they don’t tell us much about how long-term climate trends affect hurricane activity. Research like Sullivan’s, and similar work taking place in the Bahamas, can extend our knowledge back much further and help us gain a better understanding of how these storms are influenced by climate change.

“The modern record is simply too short … and there is great potential for paleohurricane records to give us more insight into the influences of climate on hurricanes,” said Jason Smerdon, a paleoclimatologist with Columbia University’s Lomont-Doherty Earth Observatory who was not involved in the study. “This kind of paleohurricane research is exciting and vital for our understanding of hurricane variability in regions like the Atlantic Basin.”

The Muyil sediment core reconstruction indicates that storm activity increased during the the North Atlantic’s Medieval Warm Period, and decreased during the period of slight global cooling called the Little Ice Age. These periods align with the movement of something called the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a band of warm air that circles the equator and oscillates between the northern and southern hemispheres. We have a 13,000-year-record of the ITCZ, and when it moves north, the sediment record shows a clear uptick in storm activity. It’s moving north right now.

The Mayan connection

Linking up the hurricane data to archeological Mayan records can serve as a reminder of the effects that periods of intense storms can have on human civilizations. The Maya Terminal Classic Phase that occurred 800-1,000 years ago came at the tail end of a prolonged drying period. This period of drought was likely brought about, in part, by deforestation driven by intense agriculture in the region. Researchers consider it a major culprit in the end of the Mayan Classic Phase, the period during which Mayan civilization is often regarded as having reached its peak.

Sullivan’s paleohurricane reconstruction adds to our understanding of the relationship between this period of Mayan history and climate change. It appears that when the rains returned, they came back with a vengeance. Increased storm activity identified in the cores coincides with the end of the Terminal Classic Period and decline of Chichen Itza.

“You have a culture that’s already sort of reeling from long-term drought and then getting hammered again,” Sullivan said. “It doesn’t stretch the imagination to envision a population recovering from drought being further stressed by frequent storms damaging crops or supply lines.”

Smerdon said he finds it “very exciting to consider how past storm activity may have influenced cultures like the Maya.” But he cautions that with just one location, it is difficult to tease out how much the fluctuations observed in the sediment are influenced by broader climate impacts on hurricanes rather than random differences in each hurricane’s path.

Sullivan is still analyzing the data and is hoping to link the sediment record to additional climate fluctuations, like El Niño. He also plans to compare this record to other cores he has collected in locations throughout the Yucatan Peninsula. Some of these extend as far back as 8,000 years, but record storm events at a lower resolution.

“The overall potential of these studies and the important insights that they can provide are well established and point to a lot of exciting work in this field over the years to come,” Smerdon said.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1637709