Two closely related anti-malarial drugs championed by President Donald Trump as promising treatments for COVID-19 appear to substantially increase the risks of death and heart complications in patients hospitalized from the disease.

That’s according to the largest study yet on the topic, which involved more than 96,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients on six continents. The peer-reviewed study, appearing Friday in The Lancet, was led by Mandeep Mehra, a professor of medicine at Harvard.

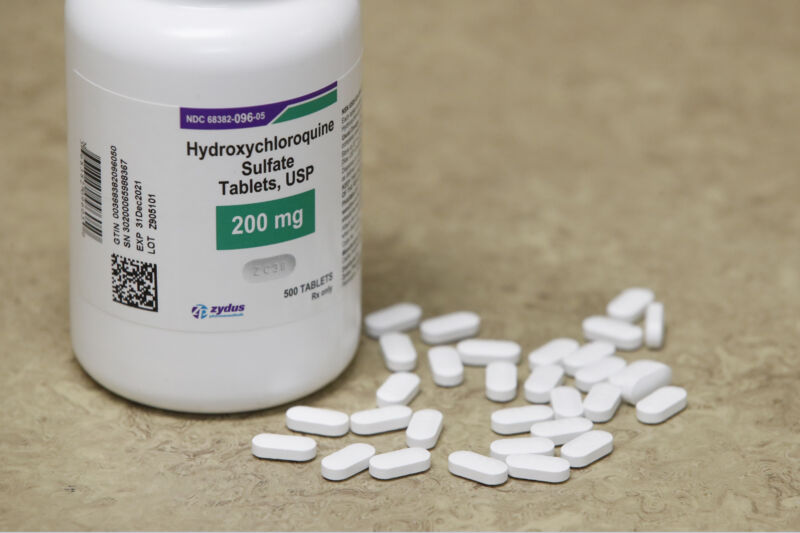

The drugs studied included chloroquine and its analogue hydroxychloroquine, which are used to treat autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as malaria. Early laboratory work suggested that they also have potent anti-viral properties. But small clinical studies looking into potential benefits for COVID-19 patients have largely provided mixed and inconclusive results to this point.

Still, some of those small, uncontrolled studies suggesting benefits have gained traction and have led to undue optimism that the drugs can treat the pandemic disease. President Trump in particular has touted the drugs, calling them a “game changer,” even this week telling reporters that he is taking hydroxychloroquine. “A couple of weeks ago I started taking it. Because I think it’s good; I’ve heard a lot of good stories,” he said Monday, May 18.

That revelation goes against a recent announcement by the US Food and Drug Administration that the drugs “should be limited to clinical trial settings or for treating certain hospitalized patients.” The FDA made the recommendation in light of reports of potentially fatal heart rhythm problems linked to the drugs, which have been given at higher doses than those used for autoimmune and malaria patients.

Sobering stats

The new, large study out today seems to bolster those concerns—and deflate overblown hopes.

Mehra and colleagues looked at the medical records of more than 96,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients from 671 hospitals in various countries. Their average age was about 54, and about 54 percent were male.

Of the patients, nearly 15,000 had received one of four treatments involving one of the drugs—1,868 received chloroquine, 3,783 received chloroquine with a macrolide antibiotic (such as azithromycin), 3,016 received hydroxychloroquine, and 6,221 received hydroxychloroquine with a macrolide (a combination Trump has also promoted). Over 81,000 other hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the study did not receive any of these regimens and were considered a control group.

The researchers primarily looked at risks of in-hospital deaths and serious heart arrhythmias.

Comparing the treatment groups to controls and adjusting each patient’s risk factors, such as congestive heart failure, the researchers found the following:

- COVID-19 patients given hydroxychloroquine alone had a 34-percent increased risk of dying in the hospital and a 137-percent increased risk of developing a serious arrhythmia.

- Those given hydroxychloroquine with a macrolide had a 45-percent increased risk of dying in the hospital and a 411-percent increased risk of developing a serious arrhythmia.

- Those given chloroquine had a 37-percent increased risk of dying in the hospital and a 256-percent increased risk of developing a serious arrhythmia.

- Those given chloroquine and a macrolide had a 37-percent increased risk of dying in the hospital and a 301-percent increased risk of developing a serious arrhythmia.

Mehra and colleagues conclude:

In this large multinational real-world analysis, we did not observe any benefit of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine (when used alone or in combination with a macrolide) on in-hospital outcomes, when initiated early after diagnosis of COVID-19. Each of the drug regimens of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with a macrolide was associated with an increased hazard for clinically significant occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias and increased risk of in-hospital death with COVID-19.

The study has some significant limitations, including that it is merely an observational study—not a randomized, controlled trial thought of as a gold standard for assessing treatments. As an observational study, it cannot prove cause and effect; it only reveals associations with the treatments. Randomized trials—several of which are currently underway—are still needed to definitely determine risks and benefits of the drug.

While the researchers tried to adjust for patients’ differing risk factors, it’s possible that other, unmeasured factors influenced the course of their illnesses. Also, the findings don’t speak to risks or outcomes for patients who are not hospitalized with COVID-19 and have milder or asymptomatic infections.

Despite the limitations, experts still say the study is enlightening. Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine highlighted in a statement to media that the study may have biases and inadequate adjustments for risks, “but it can be stated with some confidence that it is unlikely that the randomized trials will find substantial benefit to these drugs, and the excess in heart rhythm problems is consistent with everything we know about them.”

He continued: “A definitive answer still awaits the results of the randomized trials, but it is clear that the drugs should not be given for treatment of COVID-19 other than in the context of a randomized trial. It might even be said that to go on giving them other than in a trial is unethical, given this evidence that is not yet contradicted by other available evidence.”

Babak Javid, an infectious disease expert at Tsinghua University School of Medicine in Beijing, said in a statement that the study “certainly casts a great deal of doubt whether these agents are effective in the setting in which these drugs are currently being used in COVID-19 patients: i.e. severely ill patients in hospital.”

The Lancet, 2020. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1678285