Note: This is not a review of Netflix’s Space Force, but in discussing differences between the series’ first season and the real world, this article contains minor plot spoilers—but not enough to spoil 99 percent of the series’ jokes and plot developments.

One of the opening scenes of Netflix’s new comedy series Space Force hilariously depicts General Mark Naird (Steve Carell) at his first meeting as part of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

This scene establishes the premise for the main story line of the show. Comedian Dan Bakkedahl (similar to his portrayal of a congressman in Veep) plays the part of Secretary of Defense John Blandsmith. After introducing Naird as a new four-star general, Blandsmith gets to the point:

POTUS wants to make some changes. He’s tweeting about it in five minutes, so let’s hope you like it. Our nation’s internet, including Twitter, runs through our vulnerable space satellites. POTUS wants complete space dominance. Boots on the Moon by 2024! To that end, the President is creating a new branch. Space Force. This is not a joke. His words, boots on the Moon in 2024. Actually, he said boobs on the Moon, but we believe that to be a typo.

For someone who spends most days thinking and writing about space, and space policy, this is simultaneously highly entertaining and painful. I mean, it’s funny. At times during the show, I howled. And there are vivid snippets of reality throughout the series that capture the state of play in modern spaceflight. But this show takes those pieces and scrambles them madly.

The launch

One of the central tensions of the first episode involves whether or not to launch Space Force’s first big mission, a satellite on its “Epsilon” rocket. (For the record, there is a real-world Epsilon rocket, a relatively small booster developed by the Japanese Space Agency.)

Space Force’s rocket appears to be the love child of two real-world rockets: an Atlas V rocket core (which is built by United Launch Alliance) and two side-boosters that look strikingly like Falcon 9 (SpaceX) first stages with a single engine. The performance of such a rocket is interesting to contemplate, and I will give the producers of Space Force credit for doing their homework. When I was at SpaceX’s factory about a year ago working on a project, Steve Carell was there with an entourage. We brushed shoulders while getting a fountain drink in the cafeteria.

But some of the TV version’s logical lapses are, for me, too difficult to swallow. For one, Netflix’s version of Space Force is established in Colorado, which is realistic enough given existing Air Force assets there. What is completely bonkers, however, is the notion of launching orbital rockets from Colorado. Big US rockets do not launch over land because of the potential for a) an accident shortly after liftoff, and b) unless it’s a reusable rocket like the Falcon 9, the potential for a first or second stage to fall down range after its fuel is spent. With its land-based launch sites, China has a real problem with this.

Another weird conflation is weather constraints for the Epsilon launch. While conditions such as thunderstorms or high winds—either at the surface or in the upper atmosphere—can delay a launch (check out this list of constraints for the upcoming Crew Dragon launch), Space Force instead goes with humidity. Humidity?!

For the Epsilon launch, the proper humidity is 40 percent, explains Dr. Chan Kaifang (Jimmy O. Yang, Silicon Valley). The actual humidity on launch day was 54 percent. “This can effect oxygenation and fuel burn,” Kaifang explains. “If the fuel is insufficient, the rocket returns to Earth without reaching orbit.” While, yes, a rocket needs a certain amount of fuel to reach orbit, humidity has nothing to do with it.

Weird, jarring details like this emerge throughout the series—space nuts will scratch their heads at the odd array of model rockets behind Naird’s desk in his office—that suggest the producers of Space Force ultimately cared little about the details.

A confused public

Oh Berger, you’re such a nerd. And it’s true. Most of the public won’t catch these details. Nor will they care that chimpanzees are performing spacewalks, or that the interior cabin of the crew spacecraft going to the Moon is about as big as my house. None of this is plausible, but it serves the plot, and it’s often damned funny, so it’s fine.

What sort of does matter, however, is the policy stuff. It is perfectly true that President Donald Trump called for the creation of a Space Force branch of the military early in his administration, but this required Congressional action, and Congress had already been moving toward this for several years. It is also true that one of the Space Force’s primary roles is protecting our “vulnerable space satellites.” And, to the chagrin of our allies, this administration has called for space dominance.

As for the boots on the Moon thing, in the real world, the White House set a goal for a human Moon landing by 2024. Specifically, Vice President Mike Pence gets credit for this, as Trump has at times seemed more interested in Mars than the Moon. Incidentally, the show’s characterization of POTUS, who goes unnamed and does not need to be, is spot on.

However—and this is important—Pence gave this task to NASA, not the US military.

The United States essentially has three major space segments. One is the military, responsible for launching large spy satellites, GPS, its own communications satellites, an uncrewed space plane, and ensuring the safety of those space assets. It does not entail anything like Starship Troopers, however. The second is civil space, which is NASA, and which operates transparently, works with international partners, landed on the Moon in the 1960s, and is responsible for the peaceful exploration of the cosmos. Finally, there is the commercial space sector, including traditional contractors like Lockheed Martin and Boeing, as well as important new players such as SpaceX and satellite companies like Planet.

But for a fleeting, dismissive mention of NASA, Space Force mostly ignores civil and commercial space. In this television show—and thus, I fear, in the public mind—it sets up the human exploration of the Moon as a purely military exercise. There are those of us who would like to see NASA as a force to unite the world, rather than divide it, and for humans to go forward into the next frontier together.

The eerily real stuff

The show gets some details shockingly right. It portrays China as America’s major rival in space, and this is accurate. China has not yet surpassed US spaceflight capabilities, as is suggested in Space Force. However, China is building a credible and stable program that will see development of a modular space station in a couple of years, and they’re working toward putting humans on the Moon in a decade or so.

Toward the end of the first season, China claims the large “Sea of Tranquility” region on the Moon for its own as a “territory of scientific research.” China informs Naird that his astronauts should not land there because it would disrupt Chinese experiments.

As I watched this, I was reporting on NASA efforts to finalize an initiative it calls the “Artemis Accords.” The goal of these accords is to establish 10 basic norms as part of the space activities, such as operating transparently and releasing scientific data. One of these was “Deconfliction of Activities,” which affirms that no one can own territory on the Moon or elsewhere but that NASA and its partner nations can establish “safety zones,” which they would ask other nations to respect and not interfere with.

The bottom line is that Space Force exists at the very edge of real-world spaceflight. While we’re laughing, I hope we’re also thinking about how we go into deep space in the coming decade. NASA’s vision, as outlined in the Artemis Accords, is a pretty good one. I’ll take partnerships over pistols any day.

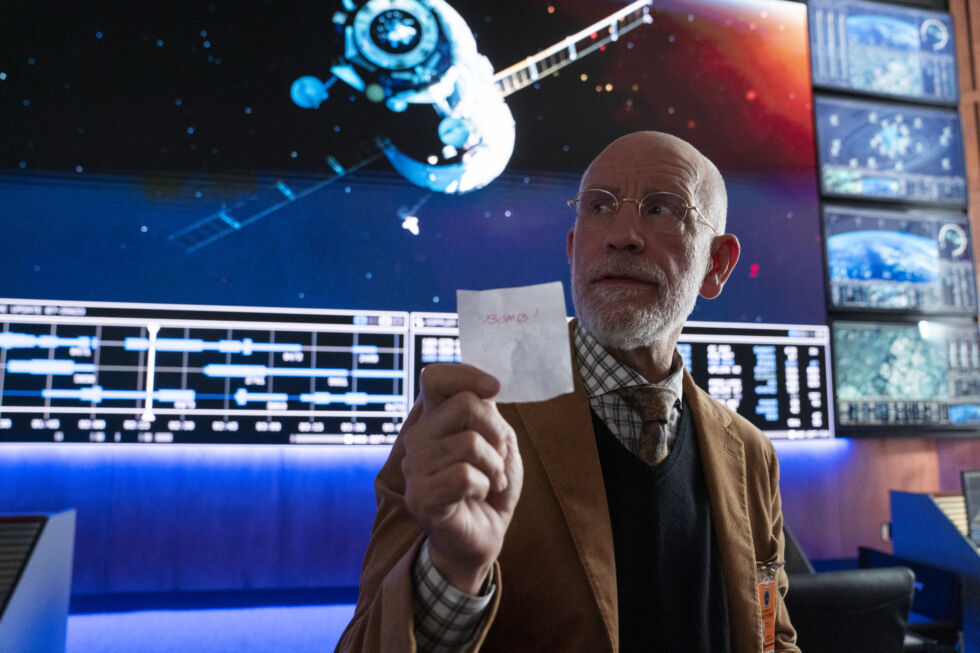

Shortly before the series’ formal Netflix premiere on Friday, May 29, some of my Ars colleagues will post a more traditional TV review of the series. Until then, I’d like to briefly fake being a TV critic and salute John Malkovich as fake Space Force’s chief scientist. My God, he’s wonderful. Steals the show.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1677703