Since the beginning of the year, the US government and private security companies have been warning of a sophisticated wave of attacks that’s hijacking domains belonging to multiple governments and private companies at an unprecedented scale. On Monday, a detailed report provided new details that helped explain how and why the widespread DNS hijackings allowed the attackers to siphon huge numbers of email and other login credentials.

The article, published by KrebsOnSecurity reporter Brian Krebs, said that, over the past few months, the attackers behind the so-called DNSpionage campaign have compromised key components of DNS infrastructure for more than 50 Middle Eastern companies and government agencies. Monday’s article goes on to report that the attackers, who are believed to be based in Iran, also took control of domains belonging to two highly influential Western services—the Netnod Internet Exchange in Sweden and the Packet Clearing House in Northern California. With control of the domains, the hackers were able to generate valid TLS certificates that allowed them to launch man-in-the-middle attacks that intercepted sensitive credentials and other data.

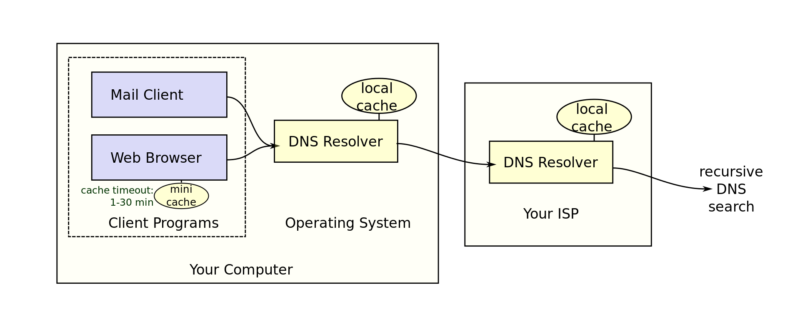

Short for domain name system, DNS acts as one of the Internet’s most fundamental services by translating human-readable domain names into the IP addresses one computer needs to locate other computers over the global network. DNS hijacking works by falsifying the DNS records to cause a domain to point to an IP address controlled by a hacker rather than the domain’s rightful owner. DNSpionage has taken DNS hijacking to new heights, in large part by compromising key services that companies and governments rely on to provide domain lookups for their sites and email servers.

Targeting key players

As an operator of one of the 13 root name servers that are critical to the functioning of the Internet, Netnod certainly qualifies as a key pillar upon which DNSpionage could support its mass hijacking spree. In late December and early January, parts of the Swedish service’s DNS infrastructure—specifically sa1.dnsnode.net and sth.dnsnode.net—were hijacked after the hackers gained access to accounts at Netnod’s domain name registrar, said Krebs, who cited interviews with the company and a statement published on February 5.

“As a participant in an international security cooperation, Netnod became aware on 2 January 2019 that we had been caught up in this wave and that we had experienced a MITM (man-in-the-middle) attack,” Netnod officials wrote in the statement. “Netnod was not the ultimate goal of the attack. The goal is considered to have been the capture of login details for Internet services in countries outside of Sweden.”

Krebs went on to report that DNS infrastructure belonging to Packet Clearing House was similarly compromised when the attackers hijacked pch.net after first gaining unauthorized access to the domain’s registrar. As it happened, falsified records for both pch.net and dnsnode.net pointed to the same sources—Key-Systems GmbH, a domain registrar in Germany, and Frobbit.se, a Swedish company.

Packet Clearing House also plays a key role in the way the Internet functions, because the nonprofit entity manages significant amounts of the world’s DNS infrastructure. The official lookups for more than 500 top-level domains are part of that infrastructure, including many in the Middle East targeted by DNSpionage.

PCH Executive Director Bill Woodcock told Krebs that DNSpionage attackers were able to alter many of the domain name records for targeted Middle East TLDs after phishing credentials that Key-Systems uses to make domain changes for their clients. Krebs wrote:

Specifically, he said, the hackers phished credentials that PCH’s registrar used to send signaling messages known as the Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP). EPP is a little-known interface that serves as a kind of back-end for the global DNS system, allowing domain registrars to notify the regional registries (like Verisign) about changes to domain records, including new domain registrations, modifications, and transfers.

“At the beginning of January, Key-Systems said they believed that their EPP interface had been abused by someone who had stolen valid credentials,” Woodcock said.

Key-Systems declined to comment for this story, beyond saying it does not discuss details of its reseller clients’ businesses.

Netnod’s written statement on the attack referred further inquiries to the company’s security director Patrik Fältström, who also is co-owner of Frobbit.se.

In an email to KrebsOnSecurity, Fältström said unauthorized EPP instructions were sent to various registries by the DNSpionage attackers from both Frobbit and Key Systems.

“The attack was from my perspective clearly an early version of a serious EPP attack,” he wrote. “That is, the goal was to get the right EPP commands sent to the registries. I am extremely nervous personally over extrapolations towards the future. Should registries allow any EPP command to come from the registrars? We will always have some weak registrars, right?”

The imperfect world of DNSSEC

The hijackings detailed in Monday’s report highlight both the effectiveness—and shortcomings—of DNSSEC, a protection that’s designed to defeat DNS hijackings by requiring DNS records to be digitally signed. In the event a record has been modified by someone without access to the private DNSSEC signing key and, therefore, the record doesn’t match the information published by the zone owner and served on an authoritative DNS server, a name server will block an end user from connecting to the fraudulent address.

Two of the three attacks on Netnod succeeded because the servers involved weren’t protected by DNSSEC, Krebs reported. A third attack, targeting infrastructure for Netnod’s internal email network that was protected by DNSSEC, underscores the limitations of the safeguard. Because the attackers already had access to the systems of Netnod’s registrar, the hackers were able to disable DNSSEC for long enough to generate valid TLS certificates for two of Netnod’s email servers.

Then something unexpected happened. Citing Netnod CEO Lars Michael Jogbäck, Krebs wrote:

Jogbäck told KrebsOnSecurity that, once the attackers had those certificates, they re-enabled DNSSEC for the company’s targeted servers while apparently preparing to launch the second stage of the attack—diverting traffic flowing through its mail servers to machines the attackers controlled. But Jogbäck said that, for whatever reason, the attackers neglected to use their unauthorized access to its registrar to disable DNSSEC before later attempting to siphon Internet traffic.

“Luckily for us, they forgot to remove that when they launched their man-in-the-middle attack,” he said. “If they had been more skilled they would have removed DNSSEC on the domain, which they could have done.”

DNSSEC performed better for Packet Clearing House, but it still had gaps there as well:

Woodcock says PCH validates DNSSEC on all of its infrastructure but that not all of the company’s customers—particularly some of the countries in the Middle East targeted by DNSpionage—had configured their systems to fully implement the technology.

Woodcock said PCH’s infrastructure was targeted by DNSpionage attackers in four distinct attacks between December 13, 2018, and January 2, 2019. With each attack, the hackers would turn on their password-slurping tools for roughly one hour and then switch them off before returning the network to its original state after each run.

The attackers didn’t need to enable their surveillance dragnet longer than an hour each time, because most modern smartphones are configured to continuously pull new email for any accounts the user may have set up on his device. Thus, the attackers were able to hoover up a great many email credentials with each brief hijack.

On January 2, 2019—the same day the DNSpionage hackers went after Netnod’s internal email system—they also targeted PCH directly, obtaining SSL certificates from Comodo for two PCH domains that handle internal email for the company.

Woodcock said PCH’s reliance on DNSSEC almost completely blocked that attack but that it managed to snare email credentials for two employees who were traveling at the time. Those employees’ mobile devices were downloading company email via hotel wireless networks that—as a prerequisite for using the wireless service—forced their devices to use the hotel’s DNS servers, not PCH’s DNSSEC-enabled systems.

With DNSSEC minimizing the effect of the hijacking of the Packet Clearing House mail server, the DNSpionage attackers, Krebs reported, resorted to a new tack. Late last month, Packet Clearing House sent customers a letter informing them that a server holding a user database had been compromised. The database stored usernames, passwords protected by the bcrypt hash function, emails, addresses, and organization names. Packet Clearing House officials said they have no evidence the attackers accessed or exfiltrated the user database, but they provided the information as a matter of transparency and precaution.

Monday’s report still leaves some key DNSpionage questions unanswered. According to an emergency directive issued last month by the Department of Homeland Security, “multiple executive branch agency domains” have been hit by the hijacking campaign. So far, there is little public information about which agencies are involved or what data, if any, has been stolen as a result.

Still, the report is the latest reminder of the importance of locking down DNS infrastructure to prevent such attacks. The lockdown measures include:

- Using DNSSEC for both signing zones and validating responses

- Using Registry Lock or similar services to help protect domain name records from being changed

- Using access control lists for applications, Internet traffic, and monitoring

- Using multi-factor authentication that must be used by all users, including subcontractors

- Using strong passwords, with the help of password managers if necessary

- Regularly reviewing accounts with registrars and other providers and look for signs of compromise

- Monitoring for the issuance of unauthorized TLS certificates for domains

Krebs’ post here has many more details.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1458663