One of the casualties of coronavirus-related social distancing measures has been public libraries, which are shut down in many communities around the world. This week, the Internet Archive, an online library best known for running the Internet’s Wayback Machine, announced a new initiative to expand access to digital books during the pandemic.

For almost a decade, an Internet Archive program called the Open Library has offered people the ability to “check out” digital scans of physical books held in storage by the Internet Archive. Readers can view a scanned book in a browser or download it to an e-reader. Users can only check out a limited number of books at once and are required to “return” them after a limited period of time.

Until this week, the Open Library only allowed people to “check out” as many copies as the library owned. If you wanted to read a book but all copies were already checked out by other patrons, you had to join a waiting list for that book—just like you would at a physical library.

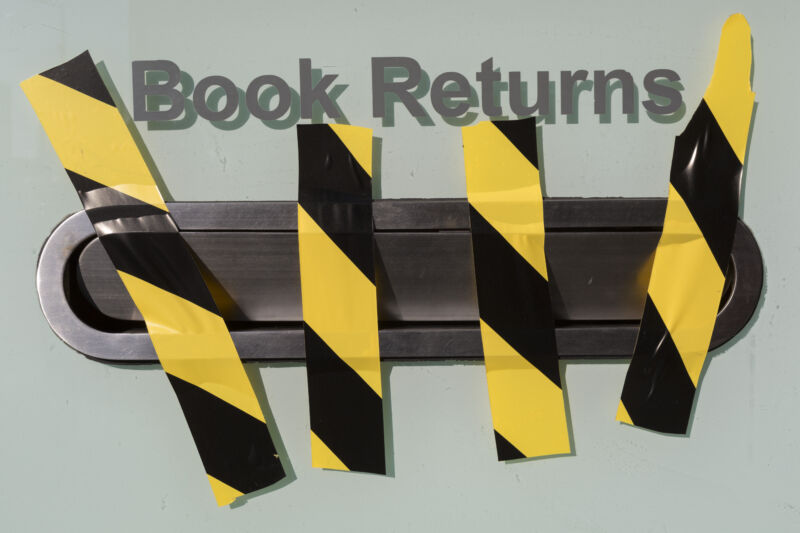

Of course, such restrictions are artificial when you’re distributing digital files. Earlier this week, with libraries closing around the world, the Internet Archive announced a major change: it is temporarily getting rid of these waiting lists.

“The Internet Archive will suspend waitlists for the 1.4 million (and growing) books in our lending library by creating a National Emergency Library to serve the nation’s displaced learners,” the Internet Archive wrote in a Tuesday post. “This suspension will run through June 30, 2020, or the end of the US national emergency, whichever is later.”

The Tuesday announcement generated significant public interest, with almost 20,000 new users signing up on Tuesday and Wednesday. In recent days, the Open Library has been “lending” 15,000 to 20,000 books per day.

“The library system, because of our national emergency, is coming to aid those that are forced to learn at home,” said Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle. The Internet Archive says the program will ensure students are able to get access to books they need to continue their studies from home during the coronavirus lockdown.

It’s an amazing resource—one that will provide a lot of value to people stuck at home due to the coronavirus. But as a copyright nerd, I also couldn’t help wondering: is this legal?

“It seems like a stretch”

The copyright implications of book scanning have long been a contentious subject. In 2005, the Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers sued Google over its ambitious book-scanning program. In 2015, an appeals court ruled that the project was legal under copyright’s fair use doctrine. A related 2014 ruling held that it was legal for libraries who participated in the program to get back copies of the digital scans for purposes such as digital preservation and increasing access for disabled patrons.

Both rulings relied on the fact that scans were being used for limited purposes. Google built a search index and only showed users brief “snippets” of book pages in its search results. Libraries only offered full-text books to readers with print disabilities. Neither case considered whether it would be legal to distribute scanned books to the general public over the Internet.

Yet the Internet Archive has been doing just that for almost a decade. A 2011 article in Publishers Weekly says that Kahle “told librarians at the recent ALA Midwinter Meeting in San Diego that after some initial hand-wringing, there has been ‘nary a peep’ from publishers” about the Internet Archive’s digital book lending efforts.

James Grimmelmann, a legal scholar at Cornell University, told Ars that the legal status of this kind of lending is far from clear—even if a library limits its lending to the number of books it has in stock. He wasn’t able to name any legal cases involving people “lending” digital copies of books the way the Internet Archive was doing.

One of the closest analogies might be the music industry’s lawsuit against ReDigi, an online service that let users “re-sell” digital music tracks they had purchased online. Copyright’s first sale doctrine has long allowed people to resell books, CDs, and other copyrighted works on physical media. ReDigi argued that the same principle should apply to digital files. But the courts didn’t buy it. In 2018, an appeals court held that transmitting a music file across the Internet creates a new copy of the work rather than merely transferring an existing file to its new owner. That meant the first sale doctrine didn’t apply.

So it seems unlikely that the first sale doctrine would apply to book lending. Could digital book lending be allowed under fair use? ReDigi tried to make a fair use argument, but the appeals court rejected it. The court “said we won’t use fair use to re-create first sale,” Grimmelmann told me in a Thursday phone interview.

In its FAQ for the National Emergency Lending program, the Internet Archive mentions the concept of controlled digital lending (CDL) and links to this site, which has a detailed white paper defending the legality of “lending” books online. The white paper acknowledges that the ReDigi precedent isn’t encouraging, but it notes that the courts focused on the commercial nature of ReDigi’s service. Perhaps the courts would look more favorably on a fair use argument from a non-profit library.

“We believe that these library uses, of all the varying digital uses, are among the most likely to be justified under a fair use rationale,” the white paper says. “Several libraries have already engaged in limited CDL for years without issue. It can be inferred that this fact indicates a tacit acknowledgement of the strength of their legal position.”

But Grimmelmann isn’t so sure. “I never want to weigh in definitively on fair use questions, but I would say that it seems like a stretch to say that you can scan a book and have it circulate digitally,” he said. He added that the fair use argument could be stronger for books that are out of print—especially “orphan works” whose copyright holder can’t be found. However, he said, “it’s a tough argument for current, in-print titles.”

And the Open Library is well stocked with titles like that. The library includes many copyrighted books that are still in print and widely available. You can check out books from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, or novels by popular authors like John Grisham or Janet Evanovich.

No one seems interested in a legal fight

The legal basis for the Open Library’s lending program may be even shakier now that the Internet Archive has removed limits on the number of books people can borrow. The benefits of this expanded lending during a pandemic are obvious. But it’s not clear if that makes a difference under copyright law. “There is no specific pandemic exception” in copyright law, Grimmelmann told Ars.

Traditionally, fair use analysis is based on four factors, including the purpose of the use and the effect on the potential market. However, these factors are not exclusive. In theory, a judge could rule that the emergency circumstances of a pandemic created a new fair use justification for online book sharing. But Grimmelmann said he couldn’t think of prior cases where courts have made that kind of leap.

So should we expect the Internet Archive to face a legal battle over its new lending program? The most obvious plaintiffs for such a lawsuit have been conspicuously silent this week. On Thursday, I sent emails to the Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers—the organizations that sued Google 15 years ago—for comment on the Internet Archive’s new library program. Neither has responded.

Two years ago, the Authors Guild blasted the Internet Archive’s lending program as a “flagrant violation of copyright law.” But as far as I can tell, they never went to court over the issue, and they don’t seem eager to start a fight now. (Update: I didn’t notice it before filing this story but the Authors Guild wrote on Friday that it was “appalled” by the National Emergency Library.)

The Internet Archive doesn’t seem that interested in discussing the legal issues here, either. The Open Library has an extensive FAQ on borrowing books, but it doesn’t have any questions about the legality of the program. When I emailed the Internet Archive asking about the legal theory behind the program, I got a response that directed me to another FAQ that doesn’t directly address the copyright issues raised by the program.

It may be that neither side would benefit from a high-profile legal battle right now. For publishers and authors, the optics of suing a library that’s expanding access to books during a pandemic would be terrible. And the Open Library’s customer base is still fairly small, so the practical financial impact for publishers and authors is likely to be small, too.

At the same time, the Internet Archive has no reason to goad the industry into a lawsuit that it has a decent chance of losing. As long as copyright holders are willing to look the other way, the Internet Archive can continue providing digital information to as many people as possible—which is why Kahle started the Internet Archive in the first place.

“This was our dream for the original Internet coming to life,” Kahle wrote on Tuesday. “The library at everyone’s fingertips.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1663571