Archaeologists have found the remains of downy pillows in the graves of two high-ranking Iron Age warriors in Sweden, dating to the 600s and 700s CE. Both warriors were buried in large boats, along with weapons, food, and horses. Down from the pillows suggests locally sourced stuffing that may have had a symbolic meaning to the people preparing the burial.

The softer side of the Iron Age

When you think of Iron Age warriors, you think of—well, you think of iron, both literal and metaphorical. And the high-ranking warriors buried in two separate boat graves at Valsgärde probably had plenty of both. Inside each 10-meter-long oarship, the deceased lay surrounded by tools for hunting and weapons for battle. Each man once wore an elaborately decorated helmet. Three shields had been laid out to cover one corpse, and the other had two shields laid across his legs.

But even the ancestors of the Vikings had a softer side. Archaeologists found brittle, tangled clumps of down beneath the shields that once covered the two warriors’ remains, and tattered bits of fabric lay above and below the feathers. The fragments were all that remained of pillows and bolsters (long cushions that lay under the pillows to prop them up) stuffed with down—the fluffy, soft, fine inner layer of feathers that helps keep birds warm.

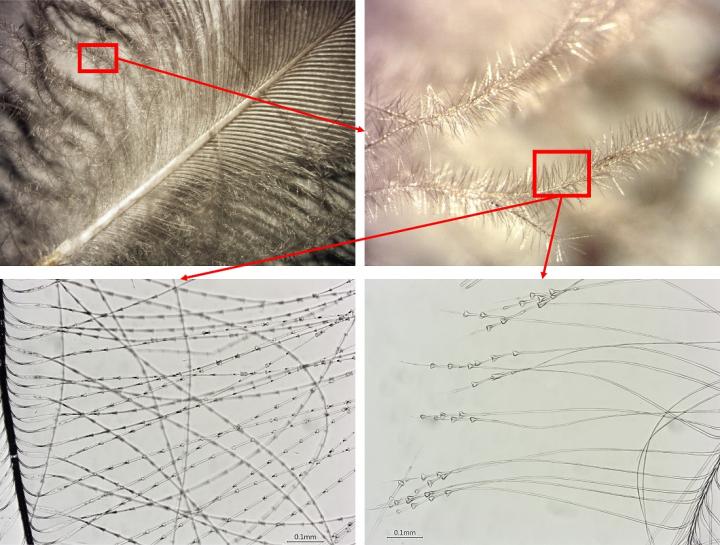

Biologist Jorgen Rosvold, of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, examined 11 samples of down from both graves under a microscope. Each bird’s downy feathers have unique characteristics. The barbs (hairlike strands that make up most of the feather) and barbules (smaller, shorter structures that branch off the barbs) have different sizes, shapes, structures, and colors, and a trained eye can use those traits to identify which family, genus, or even species of bird supplied the down.

“I’m still surprised at how well the feathers were preserved, despite the fact that they’d been lying in the ground for over 1,000 years,” said Rosvold. Even so, he said, “It was a time-consuming and challenging job for several reasons. The material is decomposed, tangled, and dirty.”

Birds of a feather

It turned out that one of the dead warrior’s cushions was stuffed mostly with duck and goose down. The other was stuffed with down from an eclectic mix of birds: geese, ducks, sparrows, crows, grouse, and chickens—and even eagle-owls, a large species of horned owl. That came as a surprise to Rosvold and Norwegian University of Science and Technology archaeologist Birgitta Berglund, who had expected to find mostly down from eider ducks, which would have been imported from farther north in Helgeland. Eider-down became a trade commodity within a few centuries after the Valsgärde burials, and Berglund and Rosvold had suspected they might find evidence of even earlier trade in the fluffy material.

Instead of trading, however, it seemed that people had simply gathered down from various birds that lived near Valsgärde. But the variety might or might not have been random. “We also think the choice of feathers in the bedding may hold a symbolic meaning,” said Berglund. “It’s exciting.”

Similar to their original idea about the eider-down trade, Berglund thinks the ancient pillow stuffing could be evidence of much older origins for Scandinavian folklore about feather beds. If she’s right, the mix of feathers in the Iron Age warriors’ pillows could have been carefully chosen for supernatural properties.

-

The burial ground at Valsgärde contains more than 90 Iron Age graves, including 15 boat burials.Berglund and Rosvald 2021

-

These warriors were etched into the metal of one warrior’s helmet.Berglund and Rosvald 2021

-

After centuries of burial, these clumbs of dirty, rotten down and a few tatters of fabric were all that remained of the once-luxurious pillows.Berglund and Rosvald 2021

-

Rosvland used modern down feathers like these for comparison when he identified the species that contributed to the ancient pillow stuffing.Berglund and Rosvald 2021

-

Each bird taxa’s feathers have a unique set of traits, like the size, shape, and number of barbules.Berglund and Rosvald 2021

-

Comparing the ancient feathers to modern ones helped identify the bird species.Berglund and Rosvald 2021

“It feels at first far-fetched that feathers in pillows and bolsters could be put there for such reasons in addition to serving as stuffing,” admitted Berglund and Rosvold in their paper. “However, Finno-Scandinavian and Danish folklore tells that there are situations where the species that the feathers came from could be considered very important.” That was especially true when it came to death and magic.

For example, the Icelandic Saga of Erik the Red goes out of its way to mention that a female shaman who visited Greenland was given the seat of honor—a cushion stuffed, specifically, with hen feathers. By the 1700s, people in Scandinavia believed that if someone was dying, bedding made with goose feathers would ease their passing, while down from certain other birds would prolong their suffering.

It’s interesting that one of the Valsgärde warriors had pillows made with some of the latter set of feathers, including chickens, crows, and owls, while the other had pillows stuffed mostly with duck and goose feathers. At this point, archaeologists have no way to know whether the difference had anything to do with a much older version of the later folklore. Perhaps it was purely a coincidence, based on which birds’ down was more available when each man died. Or perhaps the feathers were chosen based on a different piece of folklore entirely.

In any case, it’s reasonable to speculate that the contents of the bedding someone was buried with probably mattered for more than physical comfort.

Guess who who who

One of the reasons Berglund and Rosvold were so eager to study the fragile, decomposed remnants of ancient pillows is that they offered a rare chance to study how ancient people interacted with birds besides eating them. “Archaeological excavations rarely find traces of birds other than those that were used for food,” said Berglund. And one of the Valsgärde boat graves offered another fascinating piece of evidence: a headless eagle-owl buried alongside a dead Iron Age warrior. It’s morbidly reminiscent of two headless goshawks found in an Iron Age boat burial in Estonia.

Other bird bones were found among the food provisions packed into the boat, but Berglund and Rosvold say the eagle-owl was probably a hunting companion rather than a snack. Falconry arrived in Sweden in the 500s CE, and a large bird of prey like an eagle-owl would have been both a valuable asset and a status symbol. And unlike other bird bones in the boat grave, which had been butchered and packaged with other food for the final journey to the afterlife, the eagle-owl was in one piece—except for the missing head, that is.

“We believe the beheading had a ritual significance in connection with the burial,” said Berglund. “It’s conceivable that the owl’s head was cut off to prevent it from coming back.”

The beheading may have been an effort to keep the owl from coming back to life, or to keep the dead person from using the owl as a living weapon if he rose from the grave. A few centuries later, during the Viking Age, people sometimes bent the swords they buried with the dead as a way of ensuring that if the dead person rose, they couldn’t use the sword effectively against the living.

If that’s the case, it could shed light on the eagle-owl down included in this particular warrior’s pillows. “Eagle-owls are known in the Norse folklore as ghosts, and perhaps eagle-owl feathers also had such a ritual or symbolic meaning,” suggested Berglund and Rosvold.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2021 DOI 10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102828 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1752815